Try to imagine yourself in the Cretaceous Period. You get your first look at this “six foot turkey” as you enter a clearing. He moves like a bird, lightly, bobbing his head….Because Velociraptor’s a pack hunter, you see, he uses coordinated attack patterns and he is out in force today. And he slashes at you with this- a six-inch retractable claw, like a razor, on the middle toe…He doesn’t bother to bite your jugular like a lion, oh no… He slashes…you are alive when they start to eat you. So you know… try to show a little respect. Dr. Alan Grant, Jurassic Park

A view of the Hogback Monocline west of the town of Durango — the Hogback provides the terrain for the Durango Double TR. The race starts at the point marked with the “A” and climbs up and down the ribbons of rock to the east.

I have been coming to Durango, Colorado for at least 50 years. Durango is the gateway to the towering peaks and deep valleys of the San Juan Mountains in southwestern Colorado. The town is only a few hours from Los Alamos, and on many Fridays during my youth my father would pack my brothers and I up for a weekend trip to collect minerals in the La Plata Mountains (just west of Durango), or the San Juan Triangle (Silverton-Ouray-Telluride). Durango was the perfect place either to bed down before exploring on the weekend or to buy supplies for longer stays in the mountains. These trips to the mountains were probably the single most influential activity in my youth – they made me an Earthscientist, a mineral collector, a connoisseur of mining history and infected me with a love for high mountain peaks. This October I came back to run in “The Durango Double” – at least the trail run (TR) portion. The Durango Double is a celebration of running, and on Saturday there are trail runs of 25 and 50 km length, and on Sunday there are road races – a marathon and a half marathon. I came to run the 25 km TR mostly to keep in shape, and to visit one of a favorite place. My version of the “Double” will be to ride my bike on Sunday up to Molas Pass on the road to Silverton. A nice ride with an elevation gain of about 4600 feet.

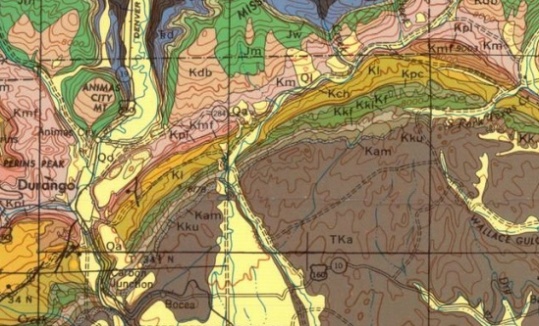

Geology Map of the Area traversed by the Durango Double. The colors denote geologic “units” or rocks of a particular age and character. The dark brown, olive, ochre colors are upper Cretaceous and mostly the Fruitland Formation.

Geology Map of the Area traversed by the Durango Double. The colors denote geologic “units” or rocks of a particular age and character. The dark brown, olive, ochre colors are upper Cretaceous and mostly the Fruitland Formation.

Durango really is a gateway; it sits between the San Juan Basin to the south and the San Juan Mountains to the north. The San Juan Basin is a tremendous energy warehouse. Sedimentary rocks that were deposited in an ancient Cretaceous ocean that ebbed and waned along a continental highland are rich in coal, natural gas and petroleum. The San Juan Basin is centered on Farmington, New Mexico, and forms a broad oval with Durango sitting at the Northern terminus. One geologic unit within the rocks of the San Juan Basin, the Fruitland Formation, has been a major source of coalbed methane – in fact in 2007-2010 the Fruitland rocks annually produced more than 1.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, making it the richest source in the United States. It also just so happens that most the Durango 25 km TR is on the dark shales and sandstones of the Fruitland formation and adjacent Kirkland formation.

A view across the Animas River (looking to the north) at the real start of the Durango Double TR. The hills are part of a major structure called the Hogback Monocline, and formally horizontal rocks dip sharply (35 degrees!) to the south towards the center of the San Juan Basin. The dark bands in the hill are black shales from the Kirkland and Fruitland formations.

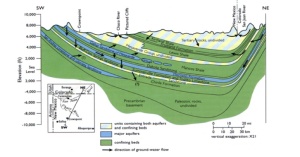

The San Juan Basin covers about 4,500 square miles in Northwestern New Mexico and a sliver of southwestern Colorado. The Basin is like a giant thumbprint pressed into a layered cake. The edges around the thumbprint are bent up and away from the center. These upturned edges are called monoclines; the Hogback Monocline runs along the northwestern margin of the San Juan Basin, and dominates the eastern and southern skyline of the town of Durango. The Durango Double TR travels along the axis of the Hogback Monocline – the ridges are formed by erosion resistant sandstone and the valleys are soft shales. The geologic cross section below shows a notional north-south slice through the San Juan Basin, and the Hogback Monocline is the upturned rocks on the right side of the figure.

Geologic cross section through the San Juan Basin. The Hogback Monocline is shown on the right hand side of the figure

The Fruitland Formation is a series of shales, and sandstones, and coal seams that were deposited in a marsh delta – not unlike the Mississippi Delta of Louisiana today. The ago of the rocks in this formation are about 75 million years, and they were deposited over a period of a couple million years. The coal is an indicator of the large amount of plant materials that decayed within the ancient marsh. There are a large number of dinosaur fossils, egg shells and tracks within the Fruitland included hadrosaurs and teeth from carnivores (thought to be from the genus of dromaeosurid theropod, which includes the velociraptor that lived 75-71 million before the present). When I run among the rocks during the Durango Double TR I can’t help but imagine what this place looked like 75 million years ago. Probably not nearly as habitable, probably more dangerous, and definitely more damp!

A storm blew through northern New Mexico and southern Colorado on Thursday and Friday, and my journey up to Durango saw quite a bit of snow on the ground near Pagosa Springs. I like “weather” when I run, but I was unsure what the TR would bring. It was 30 degrees when we lined up for the start – too cold for shorts, but the cloudless sky promised by the end of the race it would be in the 50s, which is too warm for tights. The sky was powder blue and it was a perfect day for a run!

The starting/finishing line is on an alluvial terrance above the Animas River. This photo also documents that I showed up a full hour before the race started, which is not a good idea when it is 30 degrees.

There were about 150 people in the 25 km TR, and mostly serious runners. The race starts along the road for a mile and then begins a major climb up the Carbon Junction trail. As is usually the case, I planned to go out at a steady pace and make sure I had plenty for the climbs and the end of the race. Also as usual, my plans failed me; the first mile was at an 8:55 min/mile pace, which is way too fast for me (I am a plodder not a runner). There were people all around me running fast, and like a tide I got swept up. However, once we were on the Carbon Junction trail all the pace stuff sorted out. In the second mile the trail climbs 500 feet, and it is a grind. The trail is on the Hogback now, but the material exposed is glacial outwash — a wonderful menagerie of granite boulders, schist cobbles, and even chunks of limestone. The trail surface is wonderfully soft, and easy to run.

The vista to the north at about the end of the second mile. The highest of the snow covered peaks in the distance is Engineer Mountain — the target of tomorrow’s bike ride. Not a cloud in the sky.

After mile 2 the trail is within the Kirkland and Fruitland formations. Yesterday’s snow has made the trail very muddy, and the clay content of the shales is high. There were several times that the mud actually “sucked” off my shoes. Still a nice trail, but by the top of the pass I was carrying an extra 3 pounds of the Cretaceous! At five miles the TR tops out on one of the Hogback ridge crests, and the total climb is a little over 1000 feet. A very fast decent into a closed valley called Horse Gulch. The valley is beautiful — and although most of the runners are heads down and really running, I am looking at all the remains of old coal mines. They are everywhere – but you do have to know what you are looking for. As noted, Durango is the bridge between the San Juan Basin and the San Juan Mountains. It owes its very existence to both. Durango became the smelting center for Silverton and the La Platas — trains ran down the Animas and from Hesperus bringing ore to Durango, and the abundant coal fueled smelters to process the gold and silver ores.

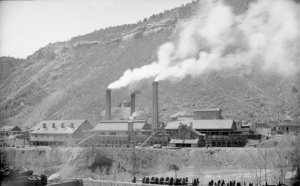

This is a picture of the American Smelting & Refining Company (ASARCO) Smelter in the early part of the 20th century. It was built on the southern side of the Animas River, and dominated the Durango skyline – it was incredibly toxic also! By the time I visited as a child the smelter had been removed, but there were huge piles of black slag (rock that was processed and melted to extract the precious metals). Today all that is gone, and unless you know Durango you see no sign of its glorious mining past.

The TR does a loop through Horse Gulch, and then heads back over the ridge – so another 600 foot climb. After reaching the ridge line I was pretty much running alone — not fast enough for the athletes, but too fast for the college kids that thought it would be cool to run a 25 km TR. The mud on the way down had just as much suction as coming up, but it seemed easier because gravity was helping pull me along to the finish line. I finished in 3 hr 9 minutes; I had really hoped to break 3 hrs, but it just wasn’t to be. At the finish line the organizers served a lunch of tacos (how can that ever be bad). I enjoyed the run most because I knew its geology, and I knew of the history of Durango. It was a visit to place in my life’s past. I did not have time to find any Cretaceous fossils, but I did ponder the sucking mud and wondered if the swamps of 75 million years ago were as sticky.