The greater part of the vast floor of the desert under us was as black as ink, and apparently smooth and level; but over a mile square of it was ringed and streaked and striped with a thousand branching streams of liquid and gorgeously brilliant fire! It looked like a colossal railroad map of the State of Massachusetts done in chain lightning on a midnight sky. Imagine it – imagine a coal-black sky shivered into a tangled network of angry fire! Mark Twain, on his visit to Kilauea in June, 1866.

Halemaumau – a crater within a crater. Halemaumau is a crater within the large summit crater of Kilauea, and has been active with lava lakes rising and falling in the last 2 years. This photo is from about a mile away and 1,500 feet above Halemaumau. The smoke is one of the main reasons the crater trail is closed. Click on any photo for full sized view.

Few things are more inspiring to a geoscientist, and disappointing to the average visitor, than the volcanoes of the Big Island of Hawaii. In the last three quarters of a million years volcanic activity has built one of the largest mountains on Earth; in geologic terms this is almost a quantum time unit! Hawaii has 5 volcanic centers (and a sixth is waiting to emerge above sea level southeast of the island) which built a land mass with a surface area of over 4000 sq miles above sea level and has two summits topping 13,600 feet (Mauna Loa at 13,680′ and Mauna Kea at 13,800′ above sea level). However, the average person that visits the Big Island is disappointed because these giants don’t have the crags and steep elevation gradients of stratvolcanoes like Mt. Rainier or Mt. St. Helens. True to their name, Hawaiian shield volcanoes the are shaped like the overturned shallow bowl shields of ancient Roman warriors.

First glimpse of Hawaii on a flight from the mainland. On the left is the summit of Mauna Kea, and in the distance is Mauna Loa. The distance between the coastline in the picture and the summit of Mauna Kea is only 20 miles – making for spectacular prominence! But, alas, for most this view does not captivate.

These gentle giants are formed by thousands of eruptions that pour out basaltic lava that has the viscosity of hot syrup – and when it cools it leaves a simple layered stack of black rock. Rarely are Hawaiian eruptions violent – no towering clouds of hot ash reaching 50,000′ above the surface of the Earth, or decapitating the tops of mountains like the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens. We like our geology violent…hence, the oft repeated comments at Volcanoes National Park, “is this all there is? where is the lava?” When Mark Twain visited kilauea in 1866 he professed to being very disappointed. He eventually warmed to the volcano, but was surprised at its “bland character”.

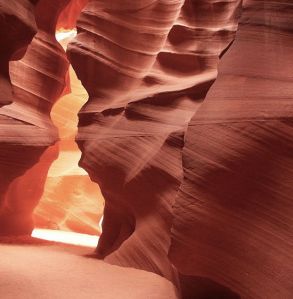

However, to the geoscientist, the enormity of Hawaii is spellbinding. So much melted rock gives witness to the dynamics of a young and hot planet. This is one of the wonders of the world that is so much bigger than mankind. I have to frequently travel to Oahu for business, and I was able to stitch together a brief vacation on the Big Island which is coincident with the recovery period after running the Antelope Canyon Ultra. There is no better way to experience geology than to run along the rocks; recovery means sore legs (and in my case very tender feet), so the runs have to be short and slow (even slower than usual). I planned a couple of short runs around Kilauea and long naps next to the wonderful beaches of the Kona Coast. Running rejuvenated my body, but Kilauea soothed my soul.

![Geologic map of the State of Hawai'i [Plate 8: Geologic map of the island of Hawai'i [scale 1:250,000]]](https://wallaceterrycjr.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/hawaii_geologic_map_1000_0.jpg?w=262&h=300)

Geologic Map of the Big Island (scale 1:250,000). The colors are largely related to age since all the rocks are pretty damn similar – basalt. From the north (top of the map) the volcanoes are Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa and Kilauea (all the red colored units).

The geology map of Hawaii resembles the tee-shirts seen at a Grateful Dead concert. Colorful and vaguely psychedelic, the map is mostly stripes delineating lava flows. The figure above shows the slow and steady march of the volcanoes to the south and east. Kohala is now extinct, and Mauna Kea’s last eruption was more than 4500 years ago. This volcanic trend, extending to all the Hawaiian Islands and the Emperor Seamount Chain located to the northwest, was one of the most mysterious geologic observations, and awaited the paradigm of plate tectonics for an explanation. In 1963 J. Tuzo Wilson proposed that a “hot spot” caused all these volcanic islands – this hot spot was an upwelling of very hot mantle material that melted through the cold oceanic plate (the Pacific Plate) as it moved to the northwest. Imagine a blow torch beneath a piece of slowing moving tar paper. The torch will melt the tar and leave a linear scar depicting the direction of motion of the tar paper. Although Wilson’s hot spot model was a huge intellectual leap forward during the formative days of plate tectonics, it is now considered to be a gross simplification of a very complex process. No matter, the theory does capture the fact that huge amounts of molten rock have reached the surface and built the Hawaiian Islands – and provides insight that Hawaii will continue to grow for millions of years into the future, with land masses emerging to the southeast of today’s Big Island (a far more benign process than what the Chinese are doing in the Spratly Islands….).

The summit of Mauna Loa from the crater of Kilauea. The passing of the guard – Kilauea is now the most active volcano in the world, and sits some 9000 feet between the summit of Mauna Loa.

Kilauea is now the center of volcanic activity on Hawaii. Eruptions might still occur on Mauna Loa (likely), Hualalai (plausible) and Mauna Kea (probably not), but Kilauea is spewing out basalt at prodigious rate, and in a few hundred thousand years will have a summit about 13,000 feet. I first visited Kilauea in 1984 as a relatively new faculty member on a boondoggle (field trips are one of the main reasons scientists choose “geology” as a profession). My visit corresponded with the one year anniversary of the an eruption on Kilauea – an eruption that has continued to today!

Peering into Kilauea Crater from smoking cliffs. The view is disconcerting – below the grassy lip of the crater there is a 1500′ drop and then a nearly flat parking lot like layer of basalt. In the distance is a second crater, Halemaumau, which presently has a lave lake 300’below its crater lip.

On that first visit I got to hike through the Kilauea Crater, and right up to Halemuamau. The 1983 eruption was producing lava several miles to the southeast of the crater, and there was little activity to indicate molten rock was ascending from some 60 km beneath the surface and collecting in shallower magma chambers. Once the lava erupted it flows down the slopes of Kilauea into the sea. The focus of volcanic activity then was along what is called the southeastern rift zone; there were occasional fountains of lava out of a crater called Pu`u `Ō`ō, but it was not visible from the Kilauea Crater.

Eruptions near Kilauea crater. Although only a few of the eruptions of Kilauea surface in the crater, there are numerous flows that constantly remake the landscape. Recovery Trail Runs were in Kilauea Iki, a path along Chain of Craters Road, and Keanakakoi Crater.

I have visited Kilauea many times since 1984, mostly because my wife had a post doctoral stint (1992-1994) with the USGS and worked on the geodetics of Kilauea. Although it is common to think of Kilauea as a shield volcano, therefore, like its older brothers Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, it is in fact very different at this stage of its development. The magma being erupted from Kilauea most closely resembles the magma erupted from Mauna Kea. So despite appearances – and being located high on the flank of Mauna Loa – Kilauea is the southwestern extension of Mauna Kea.

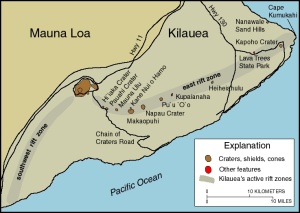

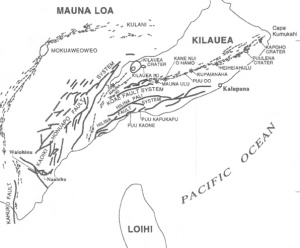

A tectonic map of Kilauea. There are three important features: the summit crater, the southwest rift and the east rift zone. As Kilauea builds on the slope of Mauna Loa the weight of eruptive lava flows “pull away” from the summit and slide towards the sea opening up the rift zones.

Every time Kilauea erupts and lava pours out, it travels down hill towards the Pacific ocean. As the lava cools it places a load on the Mauna Loa slope; this load eventually is too much for the slope to support and a wedge is “torn” away. This wedge is defined by the summit crater, southwest rift zone, and east rift zone. This “tearing” is really the odd shaped pie piece sliding downhill. The tearing opens up creates other pathways for the magma stored beneath Kilauea to erupt on to the surface. Until Kilauea grows tall enough to minimize the elevation head of Mauna Loa the rift zones will continue to have eruptions.

Picture a lava flows exposed on the Chain of Craters Road. This is actually a tilted stack of basalt sheets. I took this picture on the Chain of Craters run.

This means that the volcano is not growing in a simple way – it builds, slips, and starts a new cycle of building that could be anywhere along the rift zones or the summit. What is remarkable about the present eruption is that every part of the volcano has been active at one time or another; it started in east rift zone 10 miles from the summit and over a five year period 1 cubic mile of lava poured out. In the 1990s the Pu`u `Ō`ō crater collapsed and numerous other new, smaller craters located northwest of Pu`u `Ō`ō opened up. Eventually, the volcanic center returned to Pu`u `Ō`ō, and by 2005 another couple of cubic miles of lava had flowed forth. In 2011 the volcanic activity shifted to the Kilauea Crater and southwestern rift zone, and on April 24, 2015, lava overflowed Halema’uma’u crater within Kilauea. It was this event that ultimately led to the closing of the trails and hiking near Kilauea.

Volume of lava erupted from Kilauea in the last 200 years. The strong uptick in volcano growth on the right hand side of the chart is due to the present ongoing eruption.

It is difficult to fathom the rapid nature of the changes on Kilauea. For a geoscientist it is like watching a movie at 100 times normal viewing speed. The rocks may all look the same – black basalt – but face of the volcano is changing a rate that is similar to the changes in my own face (sags here and there, some age spots, and teeth falling out). Running on rocks younger than me – way younger in some cases – is a unique experience!

Running on the floor of Kilauea Iki. The basalt beneath my feet is from the 1959 eruption. Ever so slowly, trees are trying to reclaim the landscape.

Running on Rock Younger than Me

When I first envisioned this mini-vacation on the Big Island I thought I would try the ultimate volcano trail run — up to the summit of Mauna Loa from a trail head located near Kilauea. The run starts at 6,000′ and over 19 miles climbs 7,500′ with traverses of rough lava flows interspersed with clumps of forest. However, a 38 mile round trip — unsupported — was a total pipe dream. Especially after running a 55 km ultra only days before arriving in Hawaii. My next plan was to run through Kilauea Crater and recreate the hikes I experienced on my first visit. However, the plan was foiled when I found that the crater was off limits since the Halemaumau lava lake rose, and there was a significant increase in SO2 emissions (a very toxic gas!). This meant that I was on to plan C, the best idea anyway. I spent 2 days on 3 runs of modest distance (4-8 miles), and just enjoyed the rocks.

The trail across Kilauea Iki. The view is approximately 1 mile to the southern rim. A pathway can be made out streaking across the center of the frame.

The first run was down and across a crater located just southeast of Kilauea Crater, Kilauea Iki (see the map above – it is the green colored crater). The trail is well maintained but rocky and challenging for a run. Over a mile the path way drops 600 feet from the trail head to the Iki floor. The Iki floor is a smooth surface, occasionally interrupted by fissures and blowouts. The age of the floor is easy to calculate – it is the 1959 eruption! The rock is 3 years younger than me. The race across the crater floor is easy and relatively fast (although fast is a relative term). The run from south to north in the crater took about 14 minutes – but then there is a long climb back up towards the rim. The climb up is through thick vegetation – Iki is located right between the wet and dry side of Hawaii, and mists are a constant running companion. The total trip is 4.5 miles; but the rain and mist meant that we had the crater nearly to our selves!

One of the many bizarre basalt structures in the 1974 flow. The hole in the lower left of the figure is where the lava surrounded a tree – it eventually burned the tree away leaving a tunnel behind, and a lava clump to mark the former timber stand.

The next day I completed two other runs along the east rift zone (or more accurately, along the Chain of Craters Road). The trails here wander from small crater to small crater. Any crater older than about 30 years is being reclaimed by the vegetation. The landscape is eery and strange. Long sheets of basalt, but occasionally these sheets are covered with mounds – it sort of looks like volcanic acne. These mounds are monuments to former stands of tall trees. As the lava flowed downhill the trees impeded the progress, some lava chilled and became solid around the burning tree trucks. These chilled regions built up mounds – and today the mounds have perfect holes throughout where tree trucks where eventually burned away. The figure above is one of these basalt pimples, and you can see the round “tube” of a former trunk in the lower left of the photo. The most impressive flow on the run was from an eruption in 1974 (the same year I graduated from high school). The lava is remarkable smooth, and easy running. However, once you step off the flow it is extremely difficult running. The total distance covered was just under 8 miles. The run ends near a truly spectacular view of the ocean across a series of high cliffs, known as Pali.

Looking down towards the sea – 4 miles away, and a 2000′ drop. There are a series of steep cliffs, known as the Pali, that mark the breaking and sliding away of the stack of lava flows.

The Pali are fault scraps cutting across the lava flows – these scarps are the weak zones that fail once the load of basalt becomes too large.

Fault map of the southeastern side of Hawaii. The faults represent breakaway regions sliding the load created by the basalt towards the deep ocean. Each of the faults has a significant scar – a large cliff known as “pali” in Hawaiian.

Running down the scarps is easy work except the views are run-stopping. This trail run is all on the dry side of Hawaii, so no pesky trees to obscure the view. I was a graduate student at Caltech when seismologist began to model the seismograms from exotic sources, and the 1975 Hawaii earthquake, with an epicenter within the Pali, proved to have a source mechanism that it is consistent with a large landslide. The 1975 event is the largest Hawaiian earthquake (or, more precisely, landslide induced earthquake), and had a magnitude of 7.2 and caused a 12 m high local tsunami.

The edge of Hawaii – although the flows and pali continue far out to sea. The total elevation of Mauna Loa, as measured from the sea floor, is about 56,000 ft. Nearly twice the height of Everest, but no high camp or oxygen is required to summit.

At the ocean my runs end – sort of trivial in terms of distance, but perfect therapy for recovery from an ultra run. Actually, the real recovery was to my soul. Immersed in the geologic equivalent to a black hole, all the trials and tribulations of the last 2 months seem like back ground noise. Relaxed.