I go down to Speaker’s Corner I’m thunderstruck They got free speech, tourists, police in trucks Two men say they’re Jesus one of them must be wrong – Dire Straits, 1982 song Industrial Disease

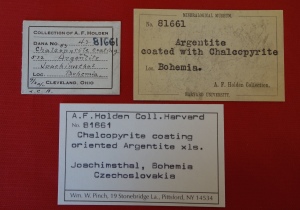

Chalcopyrite coating acanthite Joachimstal, Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic). Originally in the A.F. Holden Collection, bequeathed to the Harvard Mineral Museum, traded out and sold to William Pinch, and eventually came to my collection from dealer Cal Graeber.

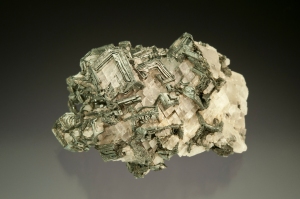

One of the questions I get asked most often when I visit a mineral show: “Is it real?”. I mean this in a mineralogical sense, not a judgement of my personality. The origin of the question is uncertainty about a mineral sample, and the particular inquiry is focused on whether the mineral is as advertised, or “fake”. The nature of fakery in the mineral hobby can be subdivided into four broad categories: (1) is the mineral actually identified correctly, (2) has the mineral specimen been enhanced, repaired or constructed, (3) is the mineral actually natural, and (4) is the ancillary information with the specimen – locality information, previous ownership, etc. – correct? To me, the last category is particularly vexing. The ancillary information, usually provided in a label or series of labels associated with a specimen, documents the history and significance of the specimen. I collect minerals partially because of the their “science” (chemistry, geology, and crystal beauty), but also because they are artifacts of history. Someone had to mine the specimen, decide it was worth keeping, pass it on to a collector or dealer that valued it, and finally making its way to my collection. From underground mine to my collection the specimen develops a patina of human history. I very much value this history — the story in the label with the mineral is part of its “worth”. The specimen pictured above is an exemplar of a mineral as a historical artifact. The specimen is a miniature sized matrix acanthite with an epitaxial coating of chalcopyrite. The locality is Joachimsthal, one of the most important historic silver mining regions in the world. The specimen has a well documented pedigree: it was in the A.F. Holden collection that was bequeathed to the Harvard Mineral Museum in 1913, and transformed Harvard’s collection from a typical university cabinet into one of the world’s greatest mineral holdings.

Labels for the chalcopyrite coating acanthite specimen pictured at the top of the article. The specimen was in the A.F. Holden collection, went to Harvard, traded to a dealer that sold it William Pinch. Eventually, Pinch sold the piece and it made its way to my collection in the 1990s.

In 1912 the Engineering and Mining Journal declared that the finest collection of minerals in the United States is “believed to be that in the American Musuem of Natural History in New York, the basis of which was the famous Bement collection. There are several important private collections. Among those, that of Col. W.A. Roebling, Trenton, N.J., is considered to be the best; anyway, the largest. Next in rank are probably the collections of A.F. Holden, Cleveland, Ohio and Fred Canfield, Dover, N.J.” Albert F. Holden graduated from Harvard in 1888 with a degree in Mining Engineering. After graduation, Holden entered the family mining business, and by 1906 he had built one of the largest mining and refining companies in the world. His holdings included what would become the Bingham Canyon copper mine in Utah, and dozens of mines spanning the mineral wealth of Alaska to Mexico. In the 1912-13 Annual Report on Harvard University, the curator of the Mineral Museum, John Wolff, wrote “received this year a mineral collection which represents the greatest single gift of minerals made during its history of one hundred and twenty years…Mr. Holden had found time in the last eighteen years to accumulate one of the finest private collections in existence….As a result, the larger part of the six thousand specimens are of the highest quality, while many are unique.” In the detailed instructions to Harvard accompanying the collection, Holden wrote “There shall be no obligation on the Museum authorities to keep any of the specimens when they have lost their scientific interest”. Although the chalcopyrite coating acanthite in my collection is modest, its tie to a mining great, and subsequent membership in the Harvard Museum, and ultimately its pathway into one of the great modern collectors, Bill Pinch, is what makes it “more” than a pretty mineral. Remove the labels, and the specimen is interesting, but it loses its significance. The tale told of specimens from labels is their character — and it is also why labels can also be used to deceive or misrepresent.

The original mineral twitter: Mineral Labels

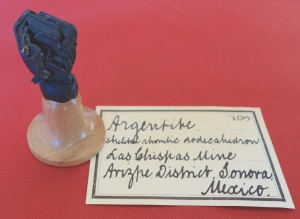

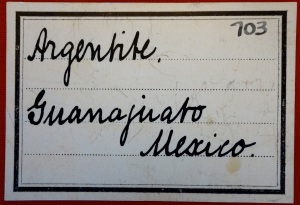

I am often surprised that many mineral collectors don’t spend much intellectual capital on the pedigree of the specimens that they pursue and collect. That statement is, of course, a gross generalization because there are many collectors that intensely focus on the specimen history, but most collectors are first and foremost interested in the perfection of the specimen itself. However, every specimen has a story to tell, and often that story is gleaned from a few lines written on an old mineral label. Although labels may only contain the briefest inscriptions, these are often delightful clues to the thoughts and passions of the original collector. The picture above is a large thumbnail of acanthite from the Las Chispas Mine, Arizpe, Mexico. For a very brief period, the first decade of the 20th century, the Las Chispas mine near Arizpe in Sonora produced some of Mexico’s largest and best specimens of polybasite crystals, large clusters of “poker chip” stephanite crystals, fine acanthite crystal clusters and a few very fine pyrargyrite specimens. Many of the specimens were saved through the enlightened efforts of mine manager Edward L. Dufourcq (1870-1919), and now populate museums and privates collections worldwide. The pictured specimen is fairly unremarkable, even if distinctive of Las Chispas acanthites. However, the label (and the wood stand that holds that displays the specimen) are what make this a historical artifact. I purchased this specimen from a dealer in 1986 – but what I saw when it was displayed in his stock was the label — it is a very distinctive “Vaux” tag! George Vaux (1863-1927) was an attorney and member of one of the most important Pennsylvanian families – in fact, he was the 9th George Vaux (and passed the name on to his son too!). George Vaux was the nephew of William S. Vaux, who one of the earliest American mineral collectors. George followed his uncle’s lead and passionately collected minerals. When he died in 1927 he had amassed an amazing collection, particularly rich in South American and Mexican specimens (Vaux’s Chanarcillo proustites are still considered some of the finest examples of what I believe is the most beautiful mineral). Vaux lived in Bryn Mawr, located west of Philadelphia, and upon his death his family kept the collection intact and on display in their home. Bryn Mawr is home to the small college of the same name, founded by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1885. In 1958 the family decided to donate his collection of more than 8,000 specimens to the college – and suddenly a small women’s liberal arts college had a major mineral holding! The transfer of the collection included Vaux’s labels – there are several types, but several thousand were the simple lined cards, with handwritten descriptions (like the one pictured above). In the early 1980s many of the Vaux specimens were traded out of the Bryn Mawr collection, including my acanthite. The wood stand and black wax mount were Vaux’s work. On the base of the stand Vaux wrote “Cahn, 11/20” which indicated that he had bought the specimen from Lazard Cahn, a Colorado Spring mineral dealer. Eventually, it was acquired by Al McGinnis (a San Mateo dealer) for his private collection, which was dispersed upon his death. A few years after I acquired the Arizpe acanthite, I found another Vaux labeled acanthite specimen in the stock of mineral dealer Gene Schlepp. In fact, the Vaux label was was tagged with the number 703, only a few digits different than the Arizpe piece!

The Vaux label stated that the specimen was Argentite (acanthite) from Guanajuato, but I suspected the specimen was actually Aguilarite (Ag4SeS), a far rarer mineral. The skeletal dodecahedrons are distinctive of the species, and the specimen looked very much like the very best aguilarites I had seen in other collections. I purchased the piece, and hurried off to the lab to do an x-ray. My hopes were confirmed – a outstanding aguilarite with history to boot!

The front of the Vaux labels only tells part of the story. Turn over a Vaux label and there is a few scribbles that connect Vaux to his mineral suppliers. Below is a picture of the Arizpe and Guanajuato labels. In Vaux’s hand writing you can see where and when he acquired the specimens. The Aguilarite was obtained from Wards in 1895 — which is very consistent with the very best samples were mined. Around 1890, Ponciano Aguilar, superintendent of the San Carlos mine at Guanajato collected an “unknown” that he thought might be Naumannite, and sent it to S.L Penfield for identification — and Penfield discovered it was a new mineral and named it in honor of Aguilar.

Back of the Vaux labels; where the specimen was purchased, when it was purchased, and a three letter code. The code is likely the purchase price.

A mystery on the Vaux labels are the three letters scribbled after the date of purchase. I have looked at about a dozen Vaux labels and they always have these initials, all different. Wendell Wilson, editor of the Mineralogical Record, suggested that this might actually be an encrypted purchase price. Several collectors from the first half of the 20th century used ciphers to record value. Martin Ehrmann used “tourmaline” as his cipher — 10, non-repeating letters, each corresponding to a numeral, 1-9 and 0 (e.g. tne would translate to 190). Carl Bosch, whose fabulous collection ended up in the Smithsonian Institution, used a similar code, with amblygonit thought to be the cipher used to record value in German Marks. I don’t have access to nearly enough of the Vaux labels to “break the code”, but it is likely that the three letters are some important secret about the specimens. Not all minerals come with a rich history, and when there is a documented pedigree it is still hard to convert that history to a monetary value. The Vaux labeled specimens in my collection are cherished by me, but in the future (hopefully distant future) when they are sold to other collectors the value will be mostly determined by comparison of the specimens with “their peers”. The aguilarite will still be one of the best in the world, with or without the label. But the real value will be the story behind the minerals – it may not be monetary value, but it will be fingerprints of humanity on stones recovered from the Earth.

When Labels Go Bad

One of specimens I treasure the most in my collection is a Bideauxite, a very rare lead-silver chloride (Pb2AgCl3(F, OH)2) from Mammoth-St. Anthony Mine, Tiger, Arizona. The photograph above is a closeup of my specimen, and displays two hexoctahedral crystals of Bideauxite associated with boleite on a quartz matrix — the crystals are tiny, only a few mm across. The unusual chemistry of Bideauxite requires a very restrictive set of conditions for formation, and in fact, the mineral is only documented to come from two localities: Tiger and a small prospect in Tarapaca, Iquique Province, in northern Chile. The species is named after the late Richard Bideaux, a good friend and a fountain of knowledge for all things mineralogy (he is co-author of the Handbook of Mineralogy), especially Arizona mineralogy (co-author of Mineralogy of Arizona). Richard “discovered” the mineral when working on his thesis at Harvard; he was going through material in the Harvard Mineral Museum from Tiger and found a tiny gray-pink fragments of a mineral he thought was chlorargyrite on boleite. Richard sent the material to Sid Williams who determined that it was a new mineral, and named it Bideauxite. In 2005, Dave Bunk bought part of the mineral collection that contained many specimens from Erberto Tealdi (the late editor of Rivista Mineralogica Italiana) collection. Tealdi collected a large suite of minerals from Colorado — and in the material Dave acquired was the most amazingly labeled sample: Bideauxite, Sherman Tunnel, Leadville, Colorado. Acquired, Rich Kosnar. Looking at the sample I immediately knew that it likely Bideauxite, but what a bizarre reference to the Sherman Tunnel! Never has there been a more ridiculous assertion for a locality — wrong geology, wrong mineralogy, and about as believable as the theory that Roman Christians established a colony on the outskirts of Tucson, Arizona around 700 AD (this theory is based on an archeology hoax, but will live forever on the internet – I love archeological hoaxes!). It is clear that the original label listing the Leadville locality was used to deceive, but really it was a rather flaccid attempt. I eventually obtained the Bideauxite from Dave Bunk, and have labeled it as from “Tiger.” This is an example of a very troubling phenomena in which the Label is Bad. In the case of the Bideauxite, the bad label has little consequence because it was so preposterous. However, for the very reason that labels add to the value of specimens — both in terms of history and monetary value — the issue of bad labels is one of the worst diseases in the mineral collecting hobby.

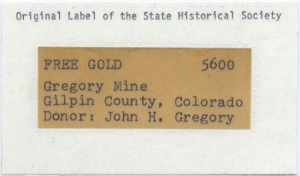

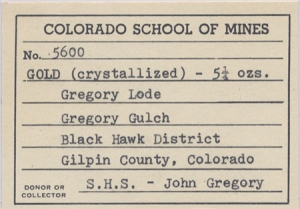

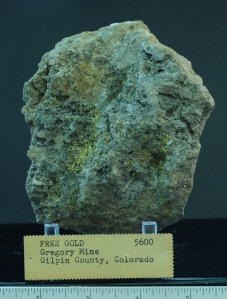

Recently, Pala Minerals published an article about the sale of arguably the most important Colorado mineral specimen — a gold sample from the early days of the Colorado’s rich mining history — in their internet newsletter (http://www.palaminerals.com/news_2014_v2.php). The specimen is fabulous – more than 5 ounces of crystallized gold that demands attention. The specimen is reputed to be from the Gregory Lode, Gregory Gulch, Gilpin County, Colorado – the label is shown below. The significance of the label is “Gregory” — as in John H. Gregory. Gregory, a prospector from Georgia, is credited with discovering the first major Colorado gold deposit located near what would become Central City, in May, 1859. Gregory sold his claims, and pretty much disappeared (although there are many Gregory legends, mostly they are unsubstantiated canard). The label changes the “Colorado Dragon” from a great mineral specimen and transforms it to a hugely signifiant historical artifact. Further, the mineral label states that the gold actually belonged to John Gregory, and that he had personally donated the treasure. There is absolutely no other evidence that Gregory collected or owned this outstanding gold, nor that he donated specimens, but the label titillates!

Label included with the Colorado Dragon. Note that it states Gregory donated this gold, even though he disappeared in the early 1860s.

The “original label” for the Colorado Dragon is stated to be from the State Historical Society. The State Historical Society received minerals originally acquired by the Colorado Bureau of Mines over a period of about 80 years, in 1956. This mineral collection was filled with history – it had specimens from senators, miners, and millionaires. The label above serves as exculpatory evidence for those that would cast doubt on the provenance of the gold. The faded piece of paper with a few typed phrases links the nugget with the birth of the Centennial State.

Eventually, the Historical Society gave the mineral specimens to the Colorado School of Mines, and it was placed into the Mineral Museum holdings. The photo of the label above is stated to be the School of Mines tag associated with the specimen. In 1990s the Colorado Dragon was obtained by Colorado Dealer Richard Kosnar (the same Kosnar associated with my bideauxite) from the School of Mines. This year the specimen was obtained by George Hickox a noted Colorado gold collector. This would be a remarkable tale, but just as the labels add immeasurable value to the gold, they also cast a dark cloud over the authenticity of the specimen. The problem is that there are at least two more specimens labeled “number 5600” – so three competitors to the throne! Two of the specimens are labels EXACTLY the same (reference to donation by Gregory, which is certifiably false) including the Colorado Dragon! Just as the tag line at the top of the blog from the Dire Straits’ song says that when two people claim to be Jesus, one must be wrong! In the case of the Gregory Gulch gold there are three competitors for the label designated 5600.

The photograph above shows a gold specimen on display at the Colorado School of Mines, and it carries the number 5600. This specimen has all the documentation to suggest that it is the original 5600, although no where is there any indication that it was donated by the original prospector. This does not mean the specimen on display is authentic. There are many reasons that the Colorado School of Mines piece could be a misrepresentation — including an attempt by someone at the School of Mines to cover up trading away the original Colorado Dragon. But that said, two specimens with the same number, and at least one of those with very questionable historical references? At the very least, one is left with a tremendous sense of uncertainty, and anger that such an important historical artifact is now tarnished. Ed Raines is the Collections Manager at the Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum, and one of the most knowledgeable professionals I know of in terms of Colorado minerals. Ed is also a bulldog – he pursues information with tremendous tenacity, and is a stickler for facts. He understands the importance of Gregory gold, and has scoured the records to shed light on the mystery. Along the way he found a third specimen labeled 5600, now in another private Colorado collection! Two is bad, three is ridiculous.

The picture above shows this third specimen, and its label — identical to the one with the Colorado Dragon. This third specimen was also acquired from Richard Kosnar. Without labels, all three golds would be interesting specimens; with the labels they become locked in the evidence room of speculation and innuendo. Just as labels add to the “value” of many specimens, these simple tags can cast doubt, and ultimately, disgust. The principals in the original transactions may know the real facts, but today there is only conflicting labels and at best, duplicate specimens. In my professional life I am asked to make judgments based on incomplete and conflicting data; I can not conclude anything from this mess other that someone(s) behaved inappropriately.

Why do Collectors Believe?

There are untold numbers of minerals that are inappropriately mated with labels. There are obvious examples where this matching is done with malfeasance – simply mineral fraud. Every collector is also familiar with unintentional mislabeling. This usually occurs when old collections have fallen to a state of disrepair, and labels become disassociated with the physical specimens. There are many tales of collecting apocalypse where carefully nurtured and curated collections that are passed along to uninterested progeny only to end up in a garage sale (I did acquire an outstanding jalpaite thumbnail in estate sale once for the princely sum of 3 dollars!). There are also many labels that are applied to specimens based on “guesses” – some are educated guesses and sometimes they are little more than wishes and hopes (my bideauxite pictured above is now labeled Tiger, but that really is just an educated guess). Unfortunately, once a label is attached to a specimen, however indelicately, it develops some credibility. This credibility resides mostly in the hearts of collectors – it is easy to blame unscrupulous dealers, but in the end it is the collector that decides the value of a specimen. The vast majority of mineral labels are above reproach; if there is something incorrect it is usually based on good intentions (e.g., when I label bideauxite as being from Tiger — no good intention is had by labeling it from Leadville!). However, there are some startling examples where mineral pedigrees that are incredulous, yet are accepted and promoted by knowledgeable collectors. This speaks to the psychology of collectors, especially the most passionate members of the hobby. Their pursuit of minerals can cloud their judgment to point of accepting the flimsiest evidence if it means they acquire something unique.

I experienced an example of this power of wishful thinking in the early 1990s when I was asked to write a chapter documenting the silver specimens in John Barlow’s collection. John had acquired an incredible jalpaite, purportedly from the Caribou Mine, located about 20 miles west of the modern city Boulder, from Richard Kosnar. John’s later recollection of the acquisition was that he was skeptical of identification, but when I first saw the specimen in his home in 1993 he presented it as the world’s finest jalpaite – it is pictured above. Peering at the fine miniature, I reacted with typical skepticism and sarcasm – I laughed. I had seen the specimen in the pictured in the Mineralogical Record years before (1976 to be exact), but in person the specimen was stunning….just not jalpaite. Laughing was probably not the best way to start a serious mineral discussion; nevertheless, John eventually had the specimen “tested” at the Smithsonian, and it was confirmed to be a chalcocite. It was a very fine chalcocite, but clearly was not from the Caribou Mine. John eventually came to terms with Kosnar, and decided that it was a chalcocite from Levant Mine in Cornwall, and had come to Colorado as a collectable by William Turnby, a partner in the Caribou mine back in the 19th century. Turnby had spent time in Cornwall, thus, this became “a plausible explanation”. This is how the specimen was labeled in John’s collection when he died. Is the Barlow label believable? Not to me.

The most disquieting aspect of this story is that John Barlow was a very knowledgeable collector – why would he accept this fanciful explanation? John was not duped into his belief by an unscrupulous dealer, but truly believed he had an amazing treasure. This tale is hardly unique – many collectors have labels that they want to believe against a preponderance of evidence.

When Specimens are Historical Artifacts, not Works of Art

Mineral collecting has as many different facets as there are collectors. For many, minerals are works of art; for others, they are expressions of science. For some collectors, including me, minerals collections are ultimately an expression of humanity. Labels tell that human story. When labels go awry – intentionally or accidently, the story of a collection is diminished. Sometimes this is inconsequential, but other times, the mislabeling is historical theft.

I would like to politely ask that my name be removed from the article. I had nothing to do with the gold sale. I wasn’t even present when the piece was sold. It was offered and purchased completely separate from me and my business.

There are a number of noted dealers (I rechecked over the weekend) that claim the blog post as written is factual. However, I have removed the the specific reference to the last sale of the gold in question.