Be still and the earth will speak to you – Navajo Proverb

Spider (home of Spider Grandmother) Rock, Canyon De Chelly, Arizona. Spider Rock rises some 750 feet above the Valley floor, and is the sacred home of one of the most important deities in the Navajo culture, Tse-che-nako. The image is looking east, and shows the separation of Canyon De Chelly and Monument Canyon. The canyons drain the highlands of the Chuska Mountains on the distant horizon. Click on any figure/photograph to get a large version.

Landscapes can be spiritual. The soaring expanse of a mountain peak can inspire; the ever shifting sands of a field of dunes makes human time seen inconsequential. Then there are some landscapes that are interwoven with humanity. Canyon De Chelly is just such a place. A narrow, twisting, dendritic chasm carved in the red sandstones of Permian Age located in the center of the Navajo Nation, Canyon De Chelly has been the home to humans for at least 2500 years. A fortuitous accident of a quarter of billion years of geology, the narrow and steep canyons provide shelter and act as a cistern for precious rain and snow that falls on distant mountains. It is impossible to peer into Canyon De Chelly and not feel the 400 generations of souls that have lived here – there are ruins and evidence of occupation in every nook and cranny; yet, the evidence of humanity blends with the landscape in a most harmonious way. It is impossible to separate rock and man; the landscape is alive.

Landsat 7 false-color image of Canyon De Chelly (acquired in on September 12, 2000). There are two main branches in the canyon complex draining the highlands of the Defiance Uplift. The northern branch is Canyon del Muerto, and the southern drainage is Canyon de Chelly (which further branches to the south in Monument Canyon). The image color scheme is tuned to highlight vegetation – the bright green in the valley floors reflects the healthy vegetation from the perennial streams. These canyons are an oasis in a harsh environment, and have been the home of humans for nearly 2500 years.

I last visited Canyon De Chelly about 20 years ago when I led a field trip of about 40 underclassmen from the University of Arizona to the northern part of the state. The students were enrolled in a class called “Geologic Disasters and Society”, and we visited faults, volcanoes, meteorite impacts, and sites of possible environmental collapse. Canyon De Chelly was the focus of the last of these “disasters”. The Canyon had a thriving – and populous – culture between 900 AD and the 13th century, and then there appeared to be a massive migration away from the Canyon, and other population centers like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon to places like southern Arizona. Twenty years ago the popular archeologic theory was that a prolonged drought stressed the urban-like centers, forcing the population to seek more productive lands. Indeed, tree ring and pollen studies indicate that the 13th century was a time of drought – however, today most archeologists think that drought was no worse than several decades in the 10th century, and by 1350 the drought was replaced by a wet period, but the population did not return. The abandonment of these population centers was probably far more complex than a simple drought – and most likely had to do with social unrest and changing religions values. The Canyon later became one of the centers of the Navajo people, and they have now have lived there for hundreds of years.

A view down Canyon De Chelly looking towards the west. The Canyon floor is verdant with cottonwoods and peach trees.

Navajo runner Shaun Martin conceived of ultra run in the spiritual lands of Canyon De Chelly in 2012. It is a place that is sacred, and the idea of a “race” is a poor fit. However, Martin preaches “This race is about running in the Navajo tradition, running as a prayer.” The inaugural ultra took place in 2013, and in 2014 I learned of the run and was extremely excited about the chance to participate. Alas, a pressing work assignment kept me from joining the 150 runners that got to view the towering cliffs and braided stream of the Canyon the way Navajos runners have done for hundreds of years. I was determined to make the run in 2015, and when fall came I was happy to travel back to the heart of the Colorado Plateau!

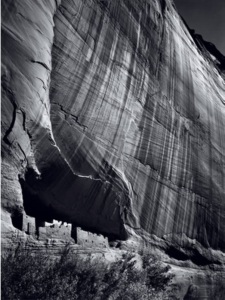

White House Pueblo, photo by Ansel Adams, 1942. The National Park Service commissioned Adams to create a photo mural for the Department of the Interior Building in DC in 1941, and he visited Canyon De Chelly twice to take pictures. The White House is named for the white streaks on the cliffs above the structure, and is one of the most iconic Anasazi ruins in the west.

Canyon De Chelly – A Slice Through the Permian

The Colorado Plateau is remarkable place; there are thousands of feet of sedimentary rock that record nearly 500 million years of the Earth’s history stacked up like a layered cake. This layered cake was deposited along the margin of the proto-North American continent and today covers about 150,000 square miles; sometimes the area of the Plateau was below sea level, sometimes it was a continental swap like the bayou of Louisiana, and sometimes is was a dry desert covered with sand dunes. Over this incredibly long time the North American continental mass suffered plate collisions, massive volcanic eruptions and huge episodes of crustal stretching and extension. Yet, the layered cake of the Plateau escaped the massive disruption that one sees in the Basin and Range of Nevada and western Arizona, or the Rocky Mountains of Colorado and New Mexico. Large scale geology maps — like those that cover the entire USA — tend to indicate that the Plateau is extremely simple. But one must look for more subtle features to realize that the Plateau has plenty of geologic character.

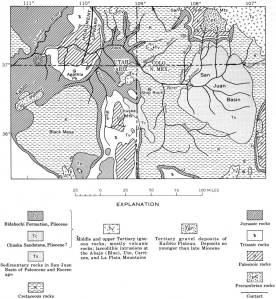

A structural map of the Colorado Plateau. Although the layered cake dominates the description of the geology, there are a series of basins and uplifts that reflect gentle folds and bends of the rocks due to episodes continental scale compressions and expansions.

There is a gentle warp that trends along a line from Black Mesa in Arizona to the San Juan Basin in New Mexico. You can imagine this “warp” as the response of firm cake that is squeezed on its sides; to accommodate the squeeze, the layered cake folds up. Ridges rise – known as anticlines – and basins fall – known as synclines. The cross-section (large very large vertical exaggeration) below shows an slice through Canyon De Chelly. To the east of the town of Chinle is a broad uplift known as the Defiance Uplift; the Chuska Mountains sits atop of an anticline.

Simplified cross section through Black Mesa, Chinle, the Chuska Mountains, and ending near Durango, Colorado. The vertical scale is very exaggerated compared to the horizontal scale.

The Defiance Uplift is the most signifiant factor in the creation of Canyon De Chelly. The highlands were slowly eroded; rain and snow that fell on the Chuska Mountains flowed in streams and rivers eroding the sediments and carving washes and canyons.

Google Earth image centered on Canyon De Chelly and Canyon Del Muerto draining the highlands of the Chuska Mountains along the right hand side of the figure. On the left hand side is Black Mesa. The canyons are cut into the De Chelly sandstone that dips to the west and descends beneath Black Mesa.

The topography of the canyons — narrow, steep walled chasms — is controlled by the nature of the sedimentary rock that has been eroded. Canyon De Chelly and Canyon Del Muerto are carved in the DeChelly sandstone, a nearly pure quartz grained rock, that is tough and strong, and can maintain vertical cliff faces hundreds of feet high. The DeChelly was formed from wind blown sand dunes. The modern day analogy for these type of sand dunes is the Namib Desert along the southwestern coast of Africa. The desert that made the DeChelly sandstone occupied a coastal plain some 250 million years ago and was long lived — probably 25 million years of blowing dunes. Finally, that desert yielded to a more hospitable environment and rivers returned depositing sandstones and shales on top of the dunes, which we call the Moenkopi formation. About 230 million years ago the last of the rocks from this period of time were deposited on top of the Moenkopi, the hard cobbles and boulders of the Shinarump conglomerate. The Shinarump is the “cap stone” above the DeChelly sandstone, and protected it from the forces of erosion for 150 million years.

Unconformity between the DeChelly sandstone (pink rocks) and the hard cap of the Shinarump conglomerate (light colored rock). Photograph taken on the north rim of Canyon Del Muerto.

The Defiance uplift bent the DeChelly sandstone and the Shinarump into a broad arch. Eventually a weakness in the Shinarump allowed the forces of erosion to attack the sandstone, and began carving the canyons. The canyons are odd – they have no real walls at the western terminus (at Chinle) or the eastern headwaters in the Chuska. The height of the walls reaches 1500 feet – at the mid-point of the headwaters and terminus.

These deeply incised canyons provided a perfect refuge for humans – the steep walls are a formidable natural defense, and the drainage captures all the waters that fall on the Chuska as snow and rain, providing a perfect – if bizarre – agriculture environment.

Mummy House, built 1000 years ago in a convex depression above the floor of Canyon Del Muerto. Photograph taken the day after the Canyon De Chelly ultra.

There is archeological evidence that humans first visited, and occasionally lived in Canyon De Chelly (and Canyon Del Muerto) a few millennia BC. However, the first year-round inhabitants began to build pit houses along the valley floors about 300 BC. The so called Basketmakers flourished for nearly a thousand years, but gradually disappeared and were replaced by the Pueblo culture, which constructed the large stone structures in the walls – they also built Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. Most of the Pueblo culture building took place between 1000 and 1280 AD. White House, Mummy Cave, Antelope House, and dozens of other communities supported a population of more than a thousand.

Pueblo culture ruins occupy scores of sites – from a few scattered towers, like in this photograph from Canyon De Chelly, to larger villages like White House.

The Pueblo culture abruptly abandoned Canyon De Chelly at the end of the 13th century. The exodus was swift and complete – and there is no consensus explanation for sudden migration. The Hopi, and later the Navajo, began to use the Canyon, and by 1700 AD it was at the center of the Navajo culture.

Spider Rock, Canyon De Chelly. This stereo pair was taken by T.H. O’Sullivan during the Wheeler expedition on 1873. The photo calls the sandstone tower “Explorer’s Column”, but it has long been considered the home of Spider Woman (Na’ashjéii Asdzáá) benefactor of humans.

The first European-American visit to the Canyon De Chelly region occurred during a punitive Spanish expedition in 1805. Lt. Antonio Narbona, the future governor of Mexico’s northern outpost — New Mexico — entered the canyon looking to confront what he characterized as Navajo aggression. Over a two day period Narbona’s troops slaughtered more than hundred Navajo women and children. The main battles occurred in the area of Massacre Cave in Canyon Del Muerto (Canyon of the Dead). Unfortunately, the unique character of the canyons that had protected the inhabitants for 2000 years served to trap the women and children. The first detailed description of the Canyon preserved in modern literature came in 1849, when Colonel John M. Washington’s explored the first few miles of the Canyon – following the route of the ultra run! In 1873 one of the great geologic surveys – the Wheeler Expedition – visited Canyon De Chelly. This expedition had one of the earliest, and foremost, photographers, Timothy H. O’Sullivan, who took some amazing photographs (the Spider Rock stereo pair shown above) that introduced the spectacular character – both geology and human – to the broader American community.

The canyon has been visited by thousands of luminaries since O’Sullivan took his photos, and the universal emotion is that this place is sacred land. The geology has made life possible here – but the inhabitants lived in the geology not simply exploiting it. It is difficult to capture in a few words that spirit of the Canyon. It has to be experienced.

The Run

Most of the ultra races I enter are mountain runs with lots of climbing (which is usually done with power walking, or, not-so-power walking). The Canyon De Chelly ultra is different – it is lots of running with a single very steep hill. I was marginally prepared in terms of training; I like to climb hills so I tend to make that my training instead of long miles at pace. On the other hand, this run is well know for its miles through soft sand on the valley floor, which is not exactly “running at pace” either. No matter, early on the morning of Oct 10 I gathered with about 160 other adventures to see Canyon De Chelly the way it was meant to be seen – not from the rim peering down hundreds, or even thousands, of feet at a distance valley floor.

Blessing of the rising sun. Facing east, the dawn to celebrated, and the runners go forth to experience the Earth.

At 6 am the runners assemble at the western end of Canyon De Chelly. Actually, the end of the Canyon is a more appropriate moniker. The steep walls of the De Chelly sandstone have plunged beneath the erosional cover of Chinle Wash, so the assembly area is a broad and sandy plain. The sky is magical – there is a crescent moon, and four planets make a solar arc across the dark sky. Mercury is just below the moon, and higher in the sky are the bright lights of Jupiter, Mars and Venus. When the glow of the impending sunrise begins, the runners gather for a morning prayer around a camp fire. With an opening in the circle of runners to the east, the Navajo prayer and blessing reminds all that running here is special — it is a privilege.

Running in the sand at the start of the race (and at the end!). The sand is soft, and even after a couple of miles the runner’s calves feel the effort.

Sometime after 7 the run starts in the cool glow of the rising sun. The course follows Canyon De Chelly wash, which is a river of soft sand. Most of the first 2.5 to 3 miles are about finding a pathway that is at least a little packed so that each stride is not an energy sucking sink into several inches of sand. My pace is about 11:30 minutes per mile, and I know it is a long day. Runners are soon spread out and form a long line of colorful shirts and running packs. The walls of the canyon slowly rise above the wash, and after a couple of miles there are shear cliffs a couple of hundred feet high framing the valley. I struggle to find a good running line, and inside my head I hear my wife telling me “run the tangent”, meaning find the shortest distance for the twisting course. Unfortunately, the tangent has nothing to do with the pathway of most packed sand!

First Ruin, about 3.5 miles into the run. Bright run highlights why the Anasazi built on the northside of the canyon — the early morning sun warmed their homes even as the most of the Canyon remained in darkness.

After a couple of miles there are some tracks along the edge of the canyon that are not sand, but hard packed clay and the running becomes easier. The first significant pueblo ruin appears about 3.5 miles into the run; appropriately named “First Ruin”, the sun shining brightly on stone houses built 1000 years ago in a crease in the De Chelly sandstone. It is pretty easy to keep a pace of 10:20-10:40 per mile from First Ruin to the first aid station at White House Ruin.

White House Ruin. Photograph taken the day before the race from the overlook on the south rim. The Ruin has both a series building in the cave and a pueblo below. The first aid station, 6 miles into the race is just to the right of this photograph.

The temperature at the start of the run was in the mid-40s. That is perfect for running an ultra! However, it is clear by 9 am that the day will bring much warmer temperatures. The course winds back and forth across the valley which expands and contracts to distances of a few hundred yards wide to more than a quarter of a mile. There are grooves of cottonwood and fruit trees that provide shade, as well as the towering walls of the south rim of the canyon. I maintain a good pace to aid station 2, located about 11 miles into the run. One of the joys to running this type of race is that the ebb and flow of pace brings you into and out of contact with other runners and you get to meet people from all over the country. I spend a couple miles chatting with the only female sergeant in Alaskan law enforcement; another mile or two with a fellow from Salt Lake City that is running his first ultra in memory of his recently departed father.

My GPS track for the run. The course starts and ends in the west — the left hand side of the map. The narrow canyons play havoc with the gps sync of my watch, and although the time of the run is accurate, I note that occasionally my watch thinks I am running at 8:30 or 16:30 per mile, when in fact I am just about 11 minutes per mile out to sharp bend to the south on the right hand side of the map. This where Bat Canyon begins.

I had a plan for the run – I always have a plan, but rarely execute it. However, today, I am almost exactly on task, and at 3 hours I have run 15.9 miles. The very first runners to pass me going back towards the start/finish are a pair of Navajo young men striding like they are floating. They pass after I have only run 14.5 miles, but given the length of the course they are beyond 20 miles! The course for the first 15 miles has been almost flat – an artifact of canyon floor. The walls of the canyon now are over a thousand feet above me, and when I arrive at Spider Rock I know that I have to climb that 1000 feet.

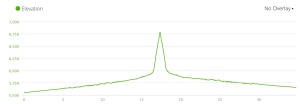

Elevation profile of the Canyon De Chelly ultra. The section from 16.25 to 17.4 is a very steep scramble up Bat Canyon. The top of Bat Canyon is the turn-around point, and tired legs need to “scramble” down before making the way back to the finish.

From Spider Rock the course turns south and heads up Bat Canyon. The first mile or so is a modest ascent, but mentally the pressure builds as I peer up the canyon and can see the rim far above me. Soon the trail becomes a very narrow single track with large boulders of red sandstone. I suppose athletes could run up this, but I am reduced to walking and using my hands to scramble. In some ways it is a relief not to be running – different muscles are used for scrambling! It is a hard ascent, but I arrive at the turn around at about 3hr 40 minutes (only a little slower than I thought I would). A good part about the scramble is that I get to look at the rocks up close, and I find large blocks of Shinarump Conglomerate, the capping rock that long protected the De Chelly sandstone from erosion.

The Shinarump Conglomerate – ancient stream channels that brought cobbles of granite and quartz pebbles from a highlands located somewhere to the northwest. The conglomerate cemented to a very hard layer of rock that resisted erosion.

Although I have stuck to my running plan I know that the second half of the race is really what all ultras are about – tired legs, all the sins of improper hydration and fueling surface, and the mental fatigue of running for 7 or 8 hours. I drink an ice cold coke at the Bat Canyon aid station, and begin the descent. It is far worse that the ascent! It is impossible to get any rhythm and the narrow track means that passing by all the runners still climbing up is like driving in stop and go traffic.

A view back down Bat Canyon towards Canyon De Chelly. The run down this steep trail is far harder for me than the scramble up.

After losing about 250 feet of elevation as I run back down Bat Canyon, I try to hop out of the narrow single track to let a faster group of runners pass by. Unfortunately, I stumble backwards and bend my bad (well, my knee that has all its original parts) knee backwards. It hurts, but seems like I can “tough it out”, and hopefully it will feel well with a mile or two. However, the knee swells, and it is quite stiff. I decide to walk for a while, and enjoy the company of a Los Alamos colleague for 2 miles.

The “back side” of Spider Rock as viewed from the end of Bat Canyon. It is only 14.5 miles back to the finish from here – but the sky is blue, and the temperature is pushing 80 degrees.

Even with the slow pace – about 17 minutes a mile – almost no runners catch us or pass. The slow pace allows time to enjoy the unique scenery, but I realize that I should do something to control the swelling. I pull out my ibuprofen, take a couple, and within minutes the swelling seems better, and even more importantly, I feel like I can run at a modest pace. I am quite relieved that I know I will make to the finish line even if my time is slower than I like. In fact, I begin to catch a few other runners, and actually feel pretty good when I arrive at the last aid station. The table is stacked with slices of locally grown melons – they taste of the nectar of the gods!

After the final aid station there is only 6 miles to run, but much of that is through the dreaded soft sand. Further, the sun is overhead, and the temperature is in the 80s. I pass about half a dozen runners, and they look totally spent. Not much I can do for them except offer encouragement – and tell them the distance remaining based on my GPS app. The last 3 miles three strangers come together – myself, a young and recent mother from Salt Lake City, and a grandmother (only a few years younger than I) from North Carolina. Good conversation and mutual support makes the 40 minutes or so of sand file by, and I finally cross the finish line in about 8 hrs 15 minutes. Tired, but elated.

The finish line area is filled with runners celebrating a spiritual journey through a special land. Traditional Navajo foods and more smiles than I can imagine. I am sore and tired, and stiffen up within a hour of completing the run. But after a night of fitful sleep — trying not to let my legs cramp or my knee to swell — I arise at 5 am and head out to the north rim of the Canyon and watch the sun rise over the Defiance Plateau. The view is wonderful, and one that I have shared with so many that passed before me in this beautiful place.