The woods are lovely, dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep, Robert Frost, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening (1923).

Star Tracks above the JMTR course. This wonderful photograph by Jim Stein (a magnificent Los Alamos photographer) shows the night sky above the track of the JMTR 50 miler and 50 km course between the Ski Hill and Pipeline Aid Stations. Click on thumbnail photos to get larger images.

On December 11, 1998, NASA launched the Mars Climate Orbiter from Cape Canaveral. The orbiter was approximately a 2 meter cube that contained several instruments designed to map the details of the Martian atmosphere, and cost approximately 330 million dollars. Nine months after launch the satellite began maneuvers to assume an orbit around the red planet – but almost immediately NASA realized something had gone wrong. The orbiter was much closer to the surface of Mars than planned, and it ultimately disintegrated in the weak Martian atmosphere. An ensuing investigation found that there was a software incompatibility in the orbiter – NASA had assumed metric units in its calculations, and controlling software supplied by Lockheed Martin used USCU (United States Customary Units). Miles vs Kilometers. Marvelous engineering, but the orbiter was lost because a kilometer is much, much different than a mile!

My home town trail ultra run, the Jemez Mountain Trail Runs (JMTR), has gained considerable fame as a challenging set of races – 50 miles, 50 km, and 15 miles (use to be a half marathon, but 13.1 miles is really just a warm up run, so it had to be stretched to 15 miles). I have run the 50 km race several times, and this year took the plunge and switched over to the 50 mile course (which is actually 52.7 miles long – ultra races have a strong culture of not wanting to “cheat” the runners and so usually run long). It is obvious to even the most causal observer, 50 miles will be a more difficult run than 50 km. But, it is not just miles (the JMTR 50 km race is 32.8 miles instead of the expected 31 miles – again, “more miles for the dollar”) that make the difference in a 50 km and 50 mile race – it is also time on one’s feet. For slower runners, like myself, the body goes through stages of trauma when you run for 13 or 14 hours (or even 8 to 10 hours for a 50 km race); these include how your body processes fuel, the cumulative impact of 10s of thousands of joint jarring strikes on the ground as you run along the trail, and blood chemistry changes as muscle tissue breaks down. A 50 miler becomes a set of different races within the overall run. Elite runners can complete the JMTR in a little over 8 hours; very talented runners can run the course in 10 to 11 hours. Plodders like myself are several hours after that, and the extra time on the trail has significant consequences that are not intuitive (i.e., just being in the sun for an extra three hours has a tremendous impact on runners).

Top of Pajarito Mountain, the high point of the JMTR course at 10,440 feet (photo taken the day before the race when I was practicing the descent to the Ski Hill Aid station). The climb to the top is relentless and long – and for 50 milers the climb is done twice. View to the west across the Valle Grande.

I have run about 20 trail ultras of 50 or 55 km length. Each of these races are unique – terrain, elevation, sand (which is the single worst running surface), weather – so it is difficult to characterize what a “typical” trail race is like. However, there are some generalities that can be made. I have run all these races in times between 6hrs and 50 minutes and 8hrs and 55 minutes (so, on average, it takes me about 8 hours to run a trail 50 km ultra). Experience has taught me when to hike and not run, how to fuel during the race, how often I need to drink, and perhaps most importantly, how to mentally deal with being on the trail for 8+ hours. It is fair to say that 50/55 km trail runs no longer intimidate me, nor do I expect to require more than a week or two to recover from a race. But all is not necessarily well: in the last 18 months I have had a noted decline in my expected performance in 50 km races. I have been slowing, and begun to cramp more often, and walked long sections of the course. The leap from metric to USCU is huge – those extra 18-20 miles, at the end of a 50 mile race, are much harder than the first 50 km. The JMTR is very known territory to me, and there is no part of the course that I have not run dozens of times. But putting those segmented runs into one long journey is a true test. 52.7 miles with 11,300 feet elevation gain (and then descent!) is a wild ride. I will turn 60 years old in a few weeks after the 2016 JMTR – and I figured “what a way to celebrate!). Unfortunately, NASA Mars missions and my ultra running have some things in common…….

Running an ultra is unlike any other athletic endeavor – there are parts physical, mental, and luck. Understanding which of these categories is making you miserable is essential. Plus, being a scientist, athletic misery allows infinite analysis!

Running Long: What Happens to the Body

There is a large body of scientific work on optimizing performance in marathons. For example this paper is a classic: Noakes, T.D., K.H. Myburgh, J. Du Plessis, L. Lang, M. Lambert, C. Van Der Riet, and R. Schall. 1991. Metabolic rate, not percent dehydration, predicts rectal temperature in marathon runners. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 23(4):443-449 (yes, the investigators convinced some runners to put a thermometer up their rectum….). One is tempted to use this catalogue of studies to understand what is happening to your body during an ultra marathon in the mountains. However, except for elite runners – the best of the best – the marathon analysis are almost irrelevant.

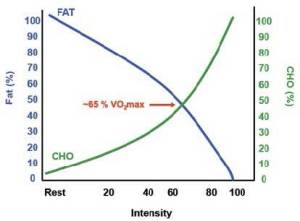

Running a marathon, even in a modest 4 hour time (and I say modest 4 hour with respect because it is really very difficult to run a 4 hour marathon!), is an intense athletic endeavor. Heart rates are typically at 80 percent max or higher, the body is relying on fast twitch muscles, and those muscles are fueled by glycogen which is stored in the muscles and liver. Typically, marathon runners store enough glycogen to run about 18 miles (and then hit the dreaded “wall” and bonk when unprepared). Ultra runners of the run-of-the-mill variety typically run at heart rates of 60 or even 50% max. My maximum heart rate is calculated to be about 165; when I run a competitive 10 km race on the road my heart rate is about 150. When I run an ultra my heart rate is usually in the 120s. This means that my body is using more slow twitch muscles, and I am burning less glycogen per mile and more fat. The figure above is a notational comparison of fuels the body utilizes as a function of intensity of exercise.

Fueling is actually one of the lesser issues for the average ultra runner. Consuming “real” food every 5 or 10 miles is much different that trying to get sugars into your system like a marathoner does. The larger issues are hydration, the general breakdown of muscle tissue and the pounding joints take with 10 hours on the trail. The impact of the muscle tissue breakdown is two fold – the muscle stop performing at their peak, and the byproducts of breakdown enter the blood stream and cause the certain internal organs to work much harder than would be expected for other forms of exercise.

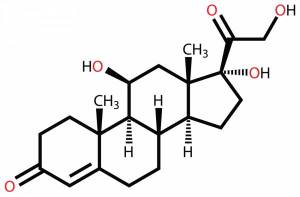

Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone – it is often called the “stress hormone – and is responsible for the stress response within the body.

There are many different things that happen with muscle breakdown – and joint pounding – but one of the most important responses in the body is the production of cortisol. Cortisol is a powerful regulator of immune response; it is a hormone controlled by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol is absolutely necessary for normal metabolic functionality. However, under stress — like hours into an ultra – cortisol becomes elevated. Elevated cortisol levels resulting from physical stress triggers the ‘fight or flight’ response. This can be good – however, over time the high levels of cortisol leads to a state of constant muscle breakdown and suppressed immune function, and a decay of things like “running efficiency”. One of the biggest differences between marathon runners and average ultra runners is the time the body is exposed to elevated levels of cortisol. Although every person responds uniquely, all humans degrade in performance over time when exposed to stress. This is not something that easily translates from one ultra runner to another.

Hydration is an essential element of metabolism. In general, ultra runners think of hydration as a response to sweating, but in fact, it is mostly a response to heavy breathing, especially in very dry climates. A small number of studies have been performed on ultra runners and they show that on average male runners will loose about 4.4 pounds during a 50 mile run lasting 12-15 hours. That weight loss is largely water. Runners probably sweat away about 8 pounds over the same run, but are able to replace about 4 of those pounds by drinking (that equates to 1/2 of a gallon of water). The rest of the loss effects other facets of the metabolism including the ability to process food and most importantly, cool the brain. Long runs always generate what is called “central fatigue” which is a gradual decline in the nervous system’s ability to contract muscles. In other words, your legs stop listening to the signals your brain sends them. “Run Forrest Run” is a pipe dream at the end of a run not only because your muscles have broken down, but also because your brain is too tired to force the issue. If your brain gets “hot” due to lack of cooling, the fatigue is greatly accelerated.

Given all these nasty things that happen during an ultra, why run? Good question, but not one that is easily answered. For me, more importantly, is “how do I understand WHY I am running the way I am” given the complexity of the human system. Running an ultra is not a controlled experiment. Every human is different – but thoughtful analysis can help understand “what happened”.

The 2016 JMTR 50 miler

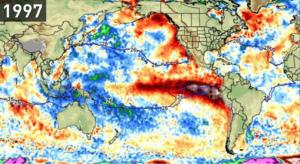

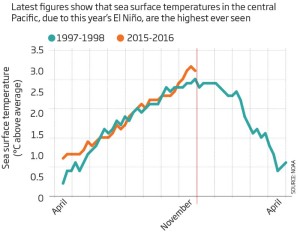

Training for the JMTR 50 was an interesting endeavor this year. Everyone in Los Alamos waited for a mega snow season promised by a massive El Nino year. Indeed the El Nino as measured by sea surface temperatures along the equator in the Pacific was the largest in recorded history.

Sea Surface temperature anomaly for the 1997 and 2015 El Nino cycles. 1997 was a devastating global event, and brought a tripling of normal moisture to the US southwest.

The climate system is quite complex so it is very difficult to “model” and predict the effects of a developing El Nino. Thus, most climate scientists and certainly most amateur weather forecasters, assume that past systems will do a pretty good job of predicting consequences for the developing system. Below are the sea surface temperature observations for 1997 and 2015 – and, indeed, they look remarkably similar. How different could the weather be in winter/spring 1998 and 2016?

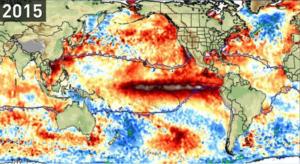

Comparisons of the sea surface temperature anomalies for December 1997 and 2015. The dark brown colors along the equator outline the “warm water pool” that drives the weather conditions that including much more precipitation in the southwest, and generally cooler temperatures.

Well, the answer is “pretty damn different”. Northern New Mexico got a significant increase in moisture, but it was incredibly uneven in its distribution. Los Alamos did not get any early snow fall; in fact it only had two large events. These storms were large enough to produce an adequate ski season, but not like that seen in 1998. The spring was colder than usual, and many small storms dumping a few inches of snow all the way up to the week of the JMTR. The net effect was that despite the modest snowfall, many of the high country trails in the Jemez were unavailable for running until late April. This meant training was done closer to town and at elevations that rarely exceeded 8000 feet elevation. Many miles were run, but the climbs were less excruciating, the air was thick (instead of what we suck down at 10,000′). When I towed the line for the 2016 50 miler I was uncertain of my fitness – the training was just different.

The JMTR starts at 5:00 am at the Posse Shack (some people get offended at the “Shack” label and prefer “Lodge”, but I grew up here in Los Alamos and we have called it the shack since the 1950s). I am always impressed at the enthusiasm of the runners before a long day ahead. However, I had some dread – it was 49 degrees at 5 am, which meant a warm day ahead. I am not a warm weather runner by any stretch of imagination. The start of the race is a dance of bouncing light beams from headlamps under a full moon sky. The first couple of miles are along a rutted single track, and nice easy running. My only thought was “not too fast, not too fast – it is a very long day”. By mile three my headlamp is in my hand, but I note that the headband is soaked with sweat. When we pull into Aid Station 1 we are 5 miles into the course — I can’t help but start the calculator in my brain and think I only have 90% to go!

GPS track of my JMTR run. The blue line looks so trivial on a oblique view of a topographic map. However, the distance covered is 32.8 miles with 6,917 feet elevation gain.

In all honesty I knew something was not right by the time I left AS 1 – I was only 3 minutes slower than the plan, but I felt like I was wearing concrete galoshes. My muscles did not hurt, but I was sweating way more than usual, and my face no doubt had the patina of lethargy. The real race starts at about mile 8.25 when the trail descends in Los Alamos Canyon and bottoms out at an elevation of 7,200 feet. Over the next 8.5 miles the trail points upward to the top of Pajarito Mountain, and an elevation of 10,440 feet. I pull out my trekking poles in Los Alamos Canyon and along steep segments I switch from a jog to a walk with an occasional power hike.

Aid Station 2 is at an elevation of 8,000 feet and at the 10 mile mark. I am pretty tired here, but friends volunteer at this station, and that buoys the spirit (plus, thinking that 20 percent of the race is done!). This is a fueling stop for me, and I grab 4 peanut and jelly squares and begin a walk up the trail. I always make the same mistake: I grab PandB because it tastes good, but it sticks to the roof of my mouth, and makes it so I can’t breath. After all these years you would think I would learn, but alas, this year is no different than all the previous races. At this point my running partner surged on ahead to assure that he could make all the cut off times along the 50 mile course.

At mile 12.4 the climb up Upper Pajarito Canyon Trail (UPCT) starts. Only 4.5 miles to the top, but the climb is 2100 feet. The grade is relentless – runnable, but barely – and there are no sections of the trail built for resting. Unfortunately for me on this day, nothing is runnable. I am into power hiking at best, and it takes 1 1/2 hours to reach the summit. I feel okay, but seem to be trapped in a gravitational well – everything is heavy and time is not particularly linear. I pause at the summit, and get out my iPhone to take a picture. However, my hands are so swollen that my finger print will not activate the phone. I fold up my trekking poles and begin what should be a quick – at least 12 or 13 minutes/mile – run down to the Ski Hill Aid Station.

Coming into AS 3, at Pajarito Ski Hill. I am right at the time I predicted for “TROUBLE”, about 45 minutes behind schedule.

The aid station is at mile 18.1. By my schedule I should have arrived at 9:30, and I had noted that if I arrive at 10:15 am then I am in trouble. I arrive at 10:17 – I am pretty despondent. I have run this segment of trail (or some approximation of it) at least 20 times in the last 3 years. Only twice before have I been slower. My wife is at the aid station, and this always lifts my spirits. I down a tall glass of coca cola, feast on watermelon, eat a handful of potato chips for salt (plus I love potato chips…), and ponder the rest of the run. My joints – in particular the one knee that has not replaced – ache, and my feet hurt. I decide to walk and trot to the next aid station and make the decision on whether to switch to the 50 km race or continue along the 50 mile route. There is a cutoff time of 12:30 pm at AS 4 for 50 milers; any runners arriving after this time MUST change to the 50 km course. I arrive at the AS in plenty of time – about 11:10 am. But this is much later than I imagined I would be here. The die is cast, and I decide I will only run the 50 km course. Better to finish a race than be stranded at a distant aid station. I call this the point of shame, or more categorically, the metric/english units point of debacle. 50 km is no 50 miles. Crash and burn in the Martian atmosphere.

There is a brief bright spot at the Pipeline Aid Station. They have ice! It seems so hot now (the weather station back at the ski hill registered a temperature of 71 degrees), and the ice is a god send. I fill my water bottle with ice (and in my mind I apologize to all the runners that will come after me because I am hogging this crystalline commodity!), and make the turn realizing I only have 12 miles to go. 12 miles is nothing – literally, a training run of 12 miles is what I do on a short day. However, I am incredibly slow – mostly walking for a couple of miles until I reach an important junction on the course between pipeline road and Guaje Ridge trail (which is almost exactly 10 miles to the finish). Just a week earlier I had been marking this section of the course with flagging, and thinking that I was going to romp down this trail at breakneck speed. Nope. The sun was blazing, and there were strong gust of wind that were so dry I was worried about becoming a mummified seismologist.

I ran the wonderful section of single track at about 15 minutes/mile. Occasionally walking for motivation, but most running. Only an ultra runner would understand the difficulty with running at this point in a race. Standing or walking there is NO pain; however, try to run, and the body just does not respond. It is curious, but it is a response to the trauma that the joints have experienced earlier in the day. After a slow 2 miles I pull into the Mitchell Trail Aid Station, and know I am only 8.1 miles from the end! 2 weekends ago I had run this last section in 1 hr and 36 minutes. Well, that past run really meant nothing. The lower Guaje Ridge trail is beautiful as far as single track is concerned – but is sort of sucks as far as being a scenic racetrack.

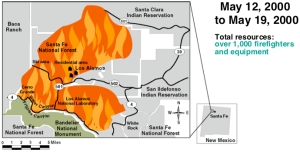

The 2000 Cerro Grande fire completely denuded Guaje Ridge. No trees were left alive, and most were burned to the ground. The lower Guaje Ridge is beginning to recover, but barely. It is a barren landscape.

The sun is blazing, and I am drinking quite a bit of water as I head out on the home stretch. As often is the case in my ultras, I drink what I think is a lot of water to accommodate my ridiculous sweating. However, I almost never have to urinate during the 8-10 hour run. I have water sloshing in the belly, but it never makes it to the badder. Today is no exception. A crude calculation indicates I have consumed about 1.6 gallons of fluid up to this point, which must have come out my pores (one of the joys of being a scientist on an ultra is that you can use that long, lonely time on the trail to calculate things – lots of things. This run I calculated the amount of fluid I consumed, the effects of Martian gravity on energy use during a run, the total amount of water I must have breathed in given a humidity of 10 percent, and of course, how I was going to survive the next four years no matter who was elected president). Although I am running okay I am mostly irritated that this section of the course is no fun. Mile after mile it is just exercise. 3 miles from the end I here a call of my name – it is my wife! She climbed up to the Mitchell Trail Aid Station, arrived 20 minutes behind me, and ran me down so she could pace me to the finish. How amazing! The last 3 miles are brutal, but as enjoyable as any I have run in the JMTR. When we pull into the last Aid Station at 30.6 miles I see so many friends volunteering. I feel like Norm walking into the bar on Cheers – everyone knows my name and are so kind and helpful. What a wonderful near-end to the race.

I still have 2 miles to the race end, and I decide just to walk. It is way slower than I have ever done, but I climb up through the deep ruts carved in the Bandolier Tuff, and stumble back into the Posse Shack. Slowest 50 km ever, but done nevertheless.

My fourth JMTR 50 km run was by far my hardest. But, the finisher pottery — front and center — was just as sweet as all the rest.

Mind over Matter (or Madder)

The JMTR has left me with worry and concern. I have seen a significant decline in my long distance running in the last 18 months. I have actually improved my short distance (10 km) speed, but anything over 3 hours seems to trigger a reaction in my body and performance wanes. I remain a determined climber, but slopes that I use to bound up I now hike up. In a few weeks I will turn 60 so there is a tendency to attribute this decline to growing older. However, it is much more precipitous than any maturity curve would suggest. I have struggled with no longer having a functioning thyroid, but again, this decline seems to outsize even that. Overtraining, under training, joint pain, workplace stress – all things that could effect my athletic performance (I barely can type athletic performance in any sentence I write about myself). I need to refocus, and consider all the possible factors, and enter the next phase of wandering in the wilderness.