This is the most beautiful place on earth…Every man, every woman, carries in heart and mind the image of the ideal place, the right place, the one true home, known or unknown, actual or visionary…For myself, I’ll take Moab, Utah…The slick-rock desert. The red dust and the burnt cliffs and the lonely sky—all that which lies beyond the end of the roads. Edward Abbey in Desert Solitaire (1968).

View across Arches National Park towards the La Sal Mountains taken the day before the Behind the Rocks Ultra. The La Sals are a Laramie laccolithic range, and sit on top of the Jurassic sandstones that have been carved into spires and arches in the Park. Click on many thumbnail photo to get a full sized view.

My first visit to Moab, Utah was in the late 1960s when I accompanied my father on a mineral collecting adventure in search of exotic uranium and vanadium minerals. Moab was perhaps the most famous modern mining boomtown in the world in the mid-1950s, but had already begun its decline by the late 1960s. I don’t recall much about the mineral collecting part of the journey, but etched in my mind was the magical vista of carved rocks only a few miles north of Moab — Arches National Monument (today it is Arches National Park). Arches was pretty much the end of the world in the late 1960s, and when we pulled in to a campsite late in the evening I don’t recall seeing another sole until we left the monument late the next evening. In the morning, as the sun rose I recall seeing a bizarre landscape of red-brown spires and towers. We hiked out a trail and saw a dozen delicate arches – improbable spans of carved rock – that defied gravity. Today I don’t recall what trail we hiked, or which arches we visited, but it was a seminal experience on my journey to becoming a naturalist.

Double Arch, in Arches National Park. This is a “pothole arch” that was formed by water erosion from above – not the standard way arches are constructed.

A few years after that visit to Moab I was enrolled in a contemporary literature class in High School, and I was assigned to read a modern novel; I picked Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness. It is a non-fiction book that really is a series of essays by Abbey about his experiences as a ranger on the Colorado Plateau. Chapter one is about Abbey’s time as a park ranger in Arches National Monument in the summer of 1956 (the year I was born). I can honestly say that Desert Solitaire, and especially chapter one, was the first book I ever read that gripped me with emotion. Abbey’s descriptions of Arches, and of the conflict and symbiosis between man and nature (with no answers by the way!) was pure passion.

I read an advertisement for an ultra run in a wilderness study area area just south of Moab, and decided it was something I had to do. I imagined running on the slick rock – the recreational name of the hard sandstones of the Colorado Plateau – and pausing to take photographs of the arches and spires would be an ultimate ultra. The race was relatively early in the year, and the miles would serve as training for the tough 50 milers to come. But the real adventure was returning to Arches.

Google Earth image of the area around Moab, Utah. The town of Moab sits in a northwest-southeast trending valley that was created by the collapse of a salt diapir. The landscape is dominated by the reddish colored Jurassic sandstones and the tall La Sal Mountains.

Carving Sandstone

The delicate arches and spires of Moab are the result of millions of years of geologic processes — there are far more rock arches (thousands!) in the area than anywhere in the world — and the story as to “why” is quite complex. The Colorado Plateau is a unique and amazing place; and every “geology” story about the Plateau has to start with the remarkable layered cake stack of sedimentary rocks that accounts for nearly 1/9 of the entire history of the Earth. As I have written before, these sandstones, limestones, shales and coal beds of the Plateau were deposited along the margin of the proto-North American continent. That ancient continent drifted from equator to equator over a period of 500 million years, but the margin of the continent was remarkably stable. Today the Plateau covers some 150,000 square miles, and has been lifted gently up to an average elevation of about 5,200′ (the mile-high table!). Wandering through the rocks today tells the long story of the continental margin; sometimes it was below sea level, sometimes it was a continental swap like the bayou of Louisiana, and sometimes is was a dry desert covered with sand dunes.

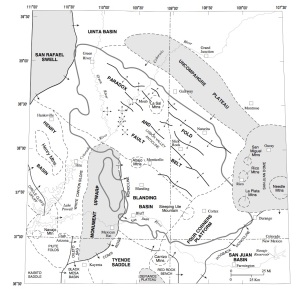

Regional tectonics of southeastern Utah (from Nuncio and Condon, 1996). The Paradox Basin is an oblong, northwest trending feature that developed some 300 million years ago. The Paradox Basin was on the margin of the Uncompahgre Uplift to the northeast, and was marine basin that occasionally was uplifted and eventually filled with a thick sequence of evaporates including salt.

The present day geology of the area around Moab began to take shape about 320 million years ago. Northeast of Moab was a large continental highlands knowns as the Uncompahgre uplift or plateau. The formation history of this highlands was complex (and still much debated), but it clearly was associated with the creation of the super continent Pangea. The highlands stretched for many hundreds of miles along the edge of the continent, and sediment was eroded from the mountains and hills and transported to the southwest and deposited in marine trough that today we call the Paradox Basin. The regional geologic map above depicts the basin as an oval – about 190km in length on a northwest-southeast axis, and 95 km across at its widest point. The filling of the Paradox basin with debris occurred during what is known as the Carboniferous Period (so named because huge deposits of coal were deposited across northern Europe, Asia, and midwestern and eastern North America). The Paradox basin had limited circulation from the ancient ocean, and would occasionally (over a period of millions of years) evaporite, and deposit salt (halite) and gypsum. This salt would later pay an extraordinary role in shaping the topography and delicate rock architecture of Moab that we see today.

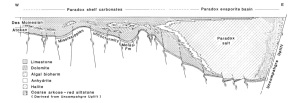

Notional geological cross section through the Paradox Basin about 310 million years before the present (from Baars and Stevenson, 1981). The “salt” contains both halite and gypsum.

The maximum salt thickness was on the order of a kilometer, although thinner on the southwestern margin of the basin. Eventually the Uncompahgre uplift met its demise, and was mostly eroded away; the Paradox Basin was subsequently covered by the great sand dunes of the Jurassic and Triassic periods (250-150 million years ago), and then the shallow marine mudstones and shales of the Cretaceous (150-70 mybp).

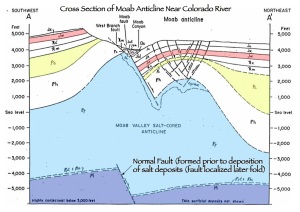

A cross section through Spanish Valley from southwest to northeast. Arches National Park is the surface on the right hand side of the figure (from Mueller, 2013). During the Laramide the geologic column was squeezed from left-to-right in the figure, and the layered cake geology was bent upward in an anticline. Eventually fractures in the hard rocks at the top of the anticline allowed water to circulate into the deep salt deposits which dissolved and moved away causing the anticline to collapse.

The large stack of sediments that covered the salt and sediments in the Paradox Basin were relatively undisturbed for several hundred million years. However, about 70 million years ago the entire west coast of the continental mass that would become North America began to be compressed and shortened. This tectonic episode was known as the Laramide Orogeny, and much of what is the western US today was faulted and thrusted into a series of basins and high mountains — imagine an accordion being squeezed. The Colorado Plateau rocks as a whole resisted the faulting, and really acted as a nearly rigid block. However, over the 30 million years of the Laramide, the Plateau began to deform and reactivating ancient deeply buried structures. In the Paradox Basin this deformation was expressed as a series of folds – synclines and anticlines. The Spanish Valley, which can be seen in the Google Earth figure above, was one of these anticlines (usually called the Moab Anticline) The anticline had a strike of northwest-southeast, and Moab is located at the northwestern end. Anticline-Syncline folding is known the world over, but there was a special ingredient in the Paradox Basin – salt! When squeezed salt does not act like a brittle rock; it flows like tar. The folding caused the salt to flow into dome-like diapirs, which further bowed up the sedimentary rocks that lay above the salt. This enhanced doming eventually fractured the overlying sedimentary rocks, which, in turn allowed surface waters to descend and interact with the salt. The salt slowly dissolved, and the resulting brine exited to the surface. This eventually called the doming sedimentary rocks to collapse. Spanish Valley is a long, collapsed anticline (the figure above shows a notional cross section near Moab). The collapse occurred along steep faults, leaving cliffs on either side of the valley. The cliffs to the southwest, which is called the Moab Rim, are much steeper and higher than those to the northeast.

Ariel view of joints in the Entrada Sandstone along the flank on the Salt Valley anticline. These joints serve as the seeds for erosion and the development of rock “fins” that eventually can form arches. From Mueller, 2013

The doming of the Jurassic sandstones above the salt beds of the Paradox Basin is a key ingredient in the creation of the rock arches that dot the Moab area. Unlike salt, sandstone is quite brittle, and responds to the doming by developing cracks, or joints. In turn, these joints allow water to penetrate into the formation, and through a process of freeze-thaw in the winter the sandstone is broken into a series of “fins” or thin slices of rock.

A view to the northwest from Windows Arches towards a whole series of sandstone fins – future arches!

These thin sheets can then be further eroded along the steep faces exposed. A complex interaction between water dissolving some of the sandstone through erosion and “stress hardening” on the remaining rock, holes are carved.

North Windows Arch. The arch was carved in a fin of Entrada Sandstone (which was formed some 160-180 million years ago from beach dunes). Below the Entrada is the Navajo sandstone.

Eventually the erosion will win, and the supporting struts of the arch will no longer be strong enough to support the span heavy rock. There are about 2000 mapped arches in Arches National Park, and about 45 have collapsed since Edward Abbey was a park ranger. No where else on Earth is there a concentration of natural stone arches that comes close to matching the Park. But the landscape is ephemeral – the great arches today will be gone in a thousand years, and replaced by new carvings. In addition to the arches there are large numbers of impressive spires and towers – all stages of the battle against erosion.

Running the Behind the Rocks 50km Ultra

Behind the Rocks is a region south of Moab on the upturned limb of the Moab Anticline. Much of the area of the ultra race skirts the Behind the Rocks Wilderness Area – and underfoot is almost exclusively the Jurassic age Navajo Sandstone. The vistas are fins and arches of Entrada Sandstone, but the Navajo controls the footing. After my disastrous experience of blisters from running in exactly the same sand at the Antelope Canyon Ultra, I was fully fortified with extra socks, bandaids, mole skin, and a magic talisman. Traveling to the starting line from Moab means a very early morning drive, and the starting line is a cold 31 degrees.

A crescent moon over the Behind Rocks Ultra starting line. First trail ultra I have been in where you are issued a chip for timing – really! For me an sand hour glass would do.

The cold temperature temperature means lots of hopping around trying to stay warm, but I know that cold is much better for me. The 50 km course mainly follows jeep trails, old and new. The newer ones are covered with fine sand, but the older ones are mostly like single track trails. The course is dominantly downhill for the first half of the race – which, unfortunately, means that it is all uphill for the miles 16-32.25!

GPS track for my version of the Behind the Rocks ultra – I say my version, because I was not always sure I was on the prescribed course – especially in the second half when I only briefly saw runners pass me with the standard “looking good buddy”. Lying is a skill ultra runners perfect.

I planned for the run out to the turn around point to take 3 hrs and 10 minutes (the turn around point is at just a hair under 16 miles). In fact, it took me 3 hrs and 18 minutes, which is probably the first time one of my ultra running plans came together (I would have actually been right on schedule if the final drop down Hunters Canyon was not apparently a bouldering course). The first 3 miles of the race are the usual madness with 150 runners sorting themselves out. I averaged 11 min/mile (I had to hold back because I knew it was a long day). The first landmark is Prostitute Butte – I have no idea as to the origin of the name, and no one I talked to had a plausible explanation.

The sun was just raising above the La Sal mountains when we arrived at Prostitute Butte a large Entrada Sandstone rock – isolated from any surrounding fins or ridges.

Running is easy in over the first 10 miles, although I am mostly passed by better runners, and only occasionally pass a newbe that went out too fast. The north side of Prostitute Butte has a nice arch named Picture Frame.

Picture Frame Arch from the ultra course. Early morning shadows subdue the contrast, but is a pretty square arch!

After mile 6.5 the course mostly follows Hunters Canyon. It is scenic and pretty easy running although there are patches that require technical acumen. There are a couple of stream crossings – mostly because it rained and snowed this week. The stream water served to cool my feet; as the sun rose it seemed that temperature jumped up to the 60s. I doubt it was that warm in the morning, but I was dripping sweat from my hat.

Descending down Hunters Canyon. There are runners ahead of me in the lower right of the photograph. I caught this group climbing out of the aid station at the turn around…perhaps a first for me.

I kept a close eye on my pace, and was very pleased that I was right on schedule….then mile 15 came, and the trail dropped down Hunters Canyon to the turn around aid station. The trail suddenly had narrow ledges, big drops where you hopped from boulder to boulder, and lots of scrambling that required both hands. Unfortunately, I still have a brace on my right hand due to a fractured thumb. It took a full twenty minutes to get to the aid station!

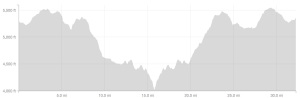

Elevation profile for the Behind the Rocks ultra. The final descent into the turn around point is as vertical as it appears in this profile. The long climb up from miles 17-24 required me to listen to my nanopod and hope that Celtic Punk would spur me on. However, the first song that came up was AC/DC and Highway to Hell….coincidence or Karma?

My total time for the ultra by my garmin watch was 7hrs 42 minutes. But, to be honest, I turned off my watch at the Hunters Canyon aid station while I changed shoes and socks, and redid the mole skin on my feet. First time in a race that I completely changed out my foot gear – it felt great, although it is debatable whether it had any effect on my performance. After the change, I switched back on the watch, and now I had to scramble up the same boulder field. Strangely, it was easier going up, and I passed at least two dozen people. But after mile 17 the course is just a grind – a constant climb. Not too steep, but relentless. I was much slower than I planned on from mile 17-24 (at least 3 minutes/mile). Runners began to pass me, but NOT runners from the 50 km race, but runners from the 50 mile race. The 50 milers started 1 hour before us, and now were passing me after having run an additional 18 miles. Wow – but I was pretty sure they did not know as much seismology as I do.

The view at mile 22 – in the background are the La Sal mountains, white capped with this weeks snow. I was hoping for some of that snow to cool me off.

The final 8 miles of the course is steep downhill, and 2 mile climb, and then what should be a nice sprint to the finish line. I was slow – finishing about 40 minutes slower than I had planned. However, It was just great to finish in under 8 hours. I drank an estimated 1.5 gallons of liquid during the race (and 4 cups of coffee before the start!), but I did not urinate during the race, or for 3 hours afterwards. Man I sweat a lot!

The swag for completing the race is a black cow bell. I assume to cheer other racers on, but it could be to wear to ward off bears.

Perfectly Fragile

I was excited to return to Moab – the geology is fabulous. However, it was not the experience I longed for. It was the last weekend for spring break for most families, and Moab was crowded with adventure seekers. Unfortunately, the adventure most of the people seek is loud and dusty. During the last few miles of the ultra race I was constantly passed by speeding dirt bikes and modified four wheel drive vehicles with grotesquely oversized tires. The isolated high altitude desert that Abbey wrote about is largely gone. It is hypocritical to wish that others did not intrude on my sense of place – today the United States has 324 million; in 1956 (the year Abbey was a park ranger here) it was 180 million. The land belongs to all the people, and I can’t claim some sense of primacy.

What I see in Moab is a collision with the delicate and fragile sense of nature in the here and now. The arches are temporary, and are something that will only be present for a million years. Eventually all the Entrada Sandstone will be gone. The fact that it is spectacularly beautiful today is a happy accident – or perhaps a challenge to humanity. I watched as families marveled at the arches; but others wanted to climb them, scuff the rock, and treat them as personal garbage. I mostly leave Moab sad.

Delicate Arch, Arches National Park. Picture is taken early the morning after the race and before the crowds arrive. What I see in the picture is a sandy beach 170 million years ago that was eventually covered and compressed to a hard sandstone. 60 million years ago it was uplifted by a salt diapir, and eventually carved into the arch people photograph daily. It will be gone within a hundred years.