May your trails be crooked, winding, lonesome, dangerous, leading to the most amazing view. Edward Abbey, in the Preface for Desert Solitaire

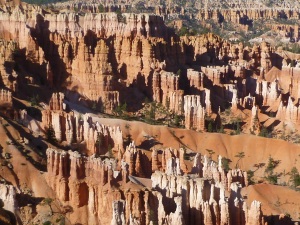

Hoodoos of Bryce Canyon, just a few miles east of the trail route for the Bryce 100. The hoodoos are erosional columns in the Claron Formation, a 30-60 million year old lake limestone.

Los Alamos, New Mexico – my hometown – sits on the eastern edge of the Colorado Plateau, an expanse of high desert and pastel hued rocks that covers more than 125,000 sq miles. The plateau is a geologic marvel; the entire geologic history of the Western United States is laid bare from the bottom of the Grand Canyon where 2 billion year old Vishnu Schist is exposed to the Pink Cliffs of Bryce Canyon in Utah which are 35 million year old sediments that were deposited in a great inland lake. The nearly 2 billion years of history is stacked like a layered cake gently tilted on its side, barely disturbed by faults and folds and other signs of geologic trauma. There is a huge gap in time – more than a billion years – between the Vishnu Schist and Tapeats Sandstone overlying it, which represents a long epoch in which the region must have stood far above sea level. Located above the 540 million year old Tapeats Sandstone there are younger rocks, which geologists can use as a yardstick of ocean invasion and retreat. Thousands of feet of sedimentary rock record the slow grinding of the ancient continents into gravel and dust. Nowhere else on Earth is the last half of a billion years of history so beautifully preserved. The western United States has suffered continental collisions, incredible crustal stretching, massive volcanic eruptions, and yet the Colorado Plateau escaped any significant deformation. The layered cake geology of the Colorado Plateau is clear road map to our geologic past!

I was looking for a 50 km trail run in southern Utah when I found the Bryce 100 (which has 3 different distances to run, including 50 km) – and it looked like a wonderful tour through a high part of the Colorado Plateau. I signed up with enthusiasm, and then realized that it was in the middle of June. I looked at the historical meteorological data at a weather station in Bryce Canyon and realized it likely to be as warm as 85 degrees on the day of the trail run. Trail runs in the heat are very much like the old saw of the frog in a pot that is brought to a slow boil (lethal, but one in which the frog is a willing participant). However, the idea of running in the footsteps of John Wesley Powell and Clarence Dutton, giants in American Geology, was enough to blind me to the dangers of hyperthermia and hypohydration.

Paria Canyon is just south of Hiway 89 traveling between Page, Arizona and Kanab, Utah. Around Paria Canyon are a number of incised channels cut through the red colored Navajo Sandstone. This sandstone was deposited on land – and the fabric in the rock was formed as crossbedding is wind blown dunes. This particular wash is one of the most famous “picture” sites that no one knows how to get to on the Colorado Plateau. The erosion across the fabric gives the appearance of waves, and this is called “The Wave”. I visited this wonderful place on my journey to the start line of the Bryce 100.

For me, a trail run is more about adventure than about being in a “race”. Seeing new places from a vantage point I have not had before, challenges, and thinking about nature are the joy of the trail. Although I live on the edge of the Colorado Plateau, I have spent far less time in the high desert than in the rougher mountains of Colorado and New Mexico. But I have an affinity for the Colorado Plateau also – the modern portrait of the geology of North America was laid out here by Powell and Dutton, who were inspired by the carved rock towers of Monument Valley and the vastness of the Grand Canyon. The Bryce 100 was a trail run and a field trip!

Geologic Giants

The 19th Century was the most remarkable period of scientific discovery in history. In fact, the “profession” of science and the term scientist was first coined in 1833. This was a time of intellectual enlightenment, and the concept that laws governed every aspect of nature and life changed human thought. Gauss, Laplace, Legrande, and Fourier invented modern mathematics; Dmitri Mendeleev invented the periodic table of elements; Lord Kelvin (Scotsman William Thomson) invented the temperature scale and formulated the second law of thermodynamics; Charles Lyell published Principles of Geology in 1830 and established the concept of uniformitarianism; Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species and established the theory of evolution.

Against the heady backdrop of new theories for life and forces governing nature, the empty “space” beyond the 100th meridian drew the interest of the nation. As the civil war ended, there was pressure to civilize and cultivate the west, but little was actually known about the region. The U.S. government decided to fund four major mapping expeditions to western half of the country — these were lead by Clarence King, George Montague Wheeler, Ferdinand Hayden, and John Wesley Powell. All these men left their signature on geology, but it was Powell that was truly a visionary. Powell lead the first successful traverse down the length of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon in 1869, and his follow-on visits to the region lead to the first modern understanding of great arid regions of the southwest. Powell eventually convinced a colleague to map the Colorado Plateau in detail – that colleague was Clarence Dutton. Dutton’s accomplishments are extraordinary, but his prodigious legacy is often overlooked.

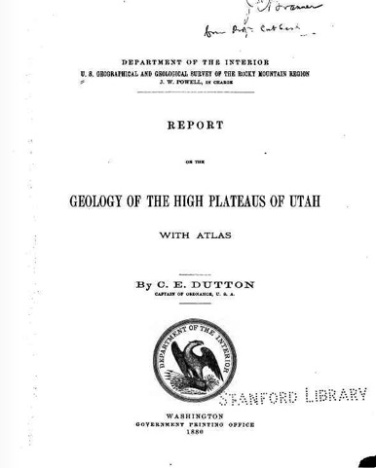

Cover page of Dutton’s classic work on the geology of the “missing” portion of the geologic map of the USA

Clarence Dutton is a hero of mine. He had remarkable insight into “how the Earth works”, and published works on geology, volcanology, and the geology of earthquakes. In 1889 he coined the phrase “isostasy” and proposed why mountains are high and valleys have low elevation. Along with this keen scientific insight came the soul of a poet. Dutton’s words paint vivid images, and he is compared to John Muir in capturing the heartbeat of a landscape. Dutton wrote the classic paper in 1880, and it remains a masterpiece.

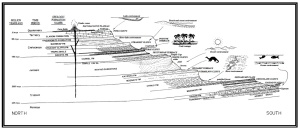

The Grand Staircase – climbing out of the Grand Canyon. The 500 million years of geologic history in the rocks preserves the entire evolutionary record of life on Earth. Figure from the Utah Geologic Survey (click on figure to enlarge).

When Dutton was doing the fieldwork for the Geology of the High Plateaus of Utah, he noted that the layered cake geology of the region created a series of steep cliffs and flat terraces that looked like a “great stairway” climbing north from the Grand Canyon. This description eventually morphed into the “Grand Staircase”, the name the region is known as now. The geologic cross section above shows the series of cliffs – there are 6 prominent cliffs as you travel the 150 miles north from the bottom of the Grand Canyon. The final stair is the Pink Cliffs which is topped by the Paunsaugunt Plateau. The Bryce 100 is run on and around the Paunsaugunt Plateau – and the top of Dutton’s Grand Staircase!

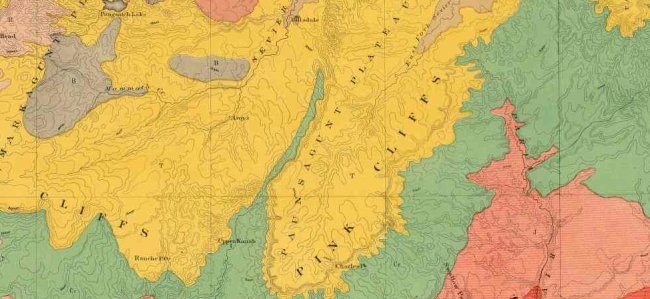

A small section fromDutton’s map “Geological map of the district of the high plateaus of Utah” centered on the area of the Bryce 100.

In Dutton’s 1880 work he published wonderful color maps to illustrate the geology. The map above is a section from Dutton that is centered on Paunsaugunt Plateau and the trail for the Bryce 100. The course travels along the western edge of the plateau, then climbs up and over the plateau to finally descends to the finish along the drainage of the East Fork Sevier River. The yellow color on the map represents the Claron Formation, which geologically is a series of lake and river deposits – sands, gravels, and cobbles along with a few limestones. The lake environment was rich in iron, and the pink color of many of the rocks is due to iron oxide staining. The rocks of the Claron are easily eroded, and the climate of the high plateau means that frost wedging plays a roll in breaking apart the strata. It is this frost wedging that produces the famous hoodoos (or rock towers) that populate the Bryce region.

Dutton wrote of the very region that the trail run traverses – the course is truly in the foot steps of a geologic giant. One last comment on Dutton (and another reason he is one of my heroes). He was an early hire into the brand new US Geologic Survey in 1875. After his outstanding work on the Colorado Plateau he worked on earthquakes and volcanoes and was promoted to the chief of the volocanology unit at the USGS. He eventually became disillusioned with the growing agency and wrote: “Our Survey is now at its zenith & I prophesy its decline. The ‘organization’ is rapidly ‘ per fecting’, i.e., more clerks, more rules, more red tape, less freedom of movement, less discretion on the part of the geologists & less outturn of scientific product. This is inevitable. It is the law of nature & can no more be stopped than the growth & decadence of the human body.” Not only do I get to share the Pink Cliffs with Dutton, but also his views on the crush of bureaucracy.

The full moon setting over the start of the race. The course heads for the moon, and then wanders around the Paunsaugunt Plateau

The Race

The Bryce 100 — which is actually a 100 and 50 miler along with a 50k — is staged out of Bryce Canyon City. “City” is a misnomer – the town sites at the edge of the national park entrance, and is a collection of hotels and various adventure companies. I chose to stay at the main hotel, Ruby’s Inn, a sprawling complex of buildings typical of concessionaire hotels in western US parks. My room is in a remote building, and everyone in the building seems to be here for the race. As I make my way to my room I pass countless rooms with their doors open – and there are stacks of water bottles, jugs of protein powder, and all sorts of stuff that ultra runners accumulate. There is a major benefit to having a hotel dedicated to the runners; lights are out at 9:30 pm, and there is nary a sound until 4:30 in the morning!

The secret to the ultra – stuff. My stuff includes Tailwind formula for my water bottles, stinger gels, Kind candy bars, lots of sun screen, and gloves for the first couple of miles

The runners are bused to the start of the race, about 7 miles from the hotel. The starting temperature is a brisk 39 degrees, but perfect conditions for running. There are about 135 runners in the 50 km race, mostly 20s and 30s somethings, and most are in running groups. I am the only person from New Mexico, but as with most trail runs, everyone is very friendly and chatty. I find 3 different geologists running the race! Clearly, the attraction to interesting geology is a big deal for this race. The course takes off to the west and climbs from 7600 feet elevation to about 8300 feet elevation over the first 6 miles. The first six miles is a roller coaster – run up 50-200 feet and then descend the same distance as the course crosses dozens of small drainages.

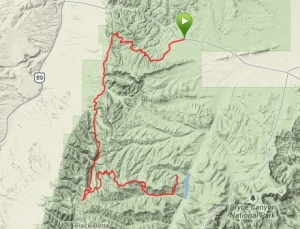

The Bryce Canyon Route for the 50 km — actually 32.6 km, and 5400 feet elevation gain. The course travels to west side of P Plateau, and climbs up and over into a drainage

The first two miles are on a forest service road – not too interesting for running. However, after two miles the course follows a wonderful single track. The track is very smooth, a consequence of the erosion of the base rock – the Claron Formation. The Claron is about 200 m thick on the Paunsaugunt Plateau, and is composed of soft, red colored siltstones and white colored limestones that are rich in sands. These sedimentary rocks were deposited in an ancient lake that was formed due to the rise of the Rocky Mountains some 70 million years before the present. The rise resulted in a basin to the west of Rockies, and Lake Claron filled this basin – at is maximum size it was similar in area to Lake Michigan. The rocks are rich in iron and manganese oxides, which give the distinctive color. Around 30 million years before the present the Colorado Plateau began a period of uplift, and Claron Lake disappeared, and the former lake bottom rocks became exposed and formed the Pink Cliffs.

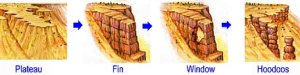

Between miles 6 and 7 the trail wanders among some wonderful hoodoos. In fact, the rocks are so interesting I am having trouble not stopping a shaping photos every couple of hundred yards! The hoodoos form because the Clarion is relatively soft, but has thin strata that are more resistant to erosion. Frost wedging plays a fairly unique roll in the hoodoo formation – cracks are filled with moisture, and when it freezes it parts the harder, more resistant limestones leaving small “caps” that eventually sit atop columns and chimneys.

Graphical explanation for the formation of Hoodoos along the Pink Cliffs. The rocks of the Claron Formation are quite soft and easily eroded – but what is unique here is the roll of frost wedging breaking apart the rock. The frequent freezing in the region causes soil moisture to freeze and expand which “pries” apart blocks of rock. Repeating this process isolates pillars, or the Hoodoos (Figure from National Park Travel)

The first 10 miles are pretty fast. I roll into the first aid station at exactly 2 hours (the station is 10.4 miles from the start). I feel fantastic, although it is getting warm – at least to me. It is 8 miles to the next aid station, and I have a plan to be there a little before the 4 hour mark. All my life I have loved maps. I am an expert at reading maps – but I fail miserably on this next section of the course. I used the course map posted on the website for the race, which shows the elevation at a very corse scale. I estimated that there would be modest climbing and descending over the 8 miles, but in fact this section of the trail is quite difficult. There is much more climbing and very slippery descending than I expect. The first thing I did when I got back to the hotel room was to download the USGS quadrangle for the region – WHAT! At the higher resolution it is obvious that this section is tough. I am embarrassed that I let scale screw me…

After the second aid station the climbing really begins. It is a lot more walking than running for me. I actually pass lots of people on the ascent of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. But the course becomes truly diabolical at mile 23. The elevation has dropped to 7700 feet, and over the next 2 miles the dusty and sandy trail climbs 1400 feet. Although most of the course up to this point has had liberal tree cover, the Pink Cliffs show no mercy or vegetation. I swear it is 100 degrees, but alas, when I check the weather record at the Bryce Canyon airport station, I find it was actually 65 degrees.

Looking north on the long climb up the Paunsaugunt Plateau. The Pink Cliffs are beautiful, and steep.

The views are breath taking, but I am toast at the final aid station, mile 25. I refill both my water bottles with Gator aid, but it is a bit too late. The trail after the aid station joins a hard packed BLM road. It is not particularly pleasant running, but the home stretch is afoot. The first couple of miles of the road actually continue the climb, and finally at mile 26.5 top out at 9200 feet elevation (by my watch). Then it is downhill! However, I just kind of amble down the road, and all those folks that passed going up the hill scream past me. I got road rash from several that passed me at a high rate of speed! I do meet several interesting people on the descent, and have conversations; I meet a young man from Monument Valley that has never run further than 13.1 miles before today. He is celebrating 6 months of sobriety, and was recently baptized – a joy to talk to. I meet a couple of people from Phoenix that have only been trail running for the last year. They are very fast until mile 29, and then absolutely die. The final part of the course is another uphill for a mile, and it is really tough.

It took me just under 8 and a half hours to finish the 32.6 miles (I love that trail runs are ALWAYS longer than the standard amount). Waiting for the bus back the Bryce Canyon City I talk to the other runners – as always, at the end, everyone is happy. The relief of finishing, and the any pain fades pretty fast. My joy was getting to wander through some unique and interesting geology. I think I will do this again.