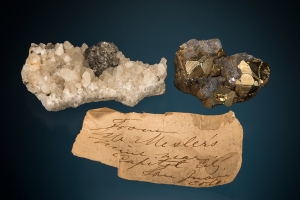

The rocks are not so close akin to us as the soil; they are one more remove from us; but they lie back of all, and are the final source of all. … Time, geologic time, looks out at us from the rocks as from no other objects in the landscape, John Burroughs, early 20th century American naturalist.

Sunset on the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, as seen from near my house in Los Alamos, NM. The course of the Santa Fe Ultra went from near the top of the high peak in the right center (Lake Peak) to the valley floor.

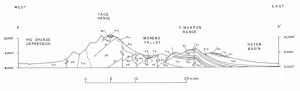

Morning sunrise in Los Alamos is a special celebration. No matter the season, the sun slowly ascends above the rugged horizon famed by the high country of the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Santa Fe Baldy, composed of PreCambrian gneiss and criss crossed with the wide pegmatite veins and dikes, begins the morning as a dark shade of gray. If clouds are present — and they often are — the skyline is crowned in an orange glow. Slowly the carved landscape of the Pajarito Plateau becomes visible; steep canyon walls framing the flat tops of mesas. Finally, the entire Rio Grande Valley nestled between Los Alamos and Baldy appears in a pastel glow. I never grow tired of the quotidian cycle, and feel blessed to live in such a wonderful place.

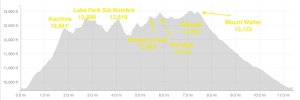

Early this year the inaugural Ultra Santa Fe race(s) was announced, and I signed up immediately. The race promised a complete tour of that distant landscape I see so many mornings. A trail circuit from the top of the ridge line at 12,000′ to the juniper covered arroyos at 7,200′ along the easter margin of the Rio Grande Valley. When I first signed up I was in the middle of training for the San Juan Solstice 50 miler, and was assuming the Santa Fe race would be the last long run of the 2016 season. However, as Yogi Berra said “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future”. The wheels fell off after the San Juan, and I was forced to scale way back on my running. No matter, I was still excited about the Ultra Santa Fe, and treated it as a true training run. 50km has long ago faded as an intimidating distance for a run, especially if there is no expectation on how fast I would run.

Many runners from Los Alamos travel over to run in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains – running from the Santa Fe Ski Valley to the top of Santa Fe Baldy is one of my very favorite training activities. I was joined by several of my friends for the Ultra Santa Fe; we all shared the trait of being undertrained at the end of the summer, so we formed a team with the name “Team DFL”. The moniker was at first whimsical, but it did prove prothetic! However, that did not diminish the adventure of traveling through a mountain wilderness, and the joy of friendship.

Team DFL (Dave Zerkle, Terry Wallace and Dave Dogruel) at the beginning of the Ultra Santa Fe 50km (really it was 56 km). Photo from Carl Gable.

The Race

It takes about 1hr 15 minutes to drive from Los Alamos to the Santa Fe Ski Valley, so we departed about 5 am from the hill. This left way more time that was necessary, but it also allowed the copious consumption of coffee (not really a performance enhancing substance, but rather, the lack of coffee is a well known performance depressant). The temperature at start time was in the mid-40s, perfect for running. The logistics of putting on any Ultra is challenging, and certainly the chance of a first-time event having a “hiccup” is high. However, the crew that put on the Ultra Santa Fe were commendable. A few hours earlier in the dark, 24 runners had started the 50 mile version of the race. The 50 km and 50 mile courses shared much of the same trail, and Race Director gave detailed instructions to the runners on how “not to confuse” the courses. A few hours after our 50 km start there would be a half marathon, which also shared some of the same trail….because it was later in the day, why listen to that instruction, eh?

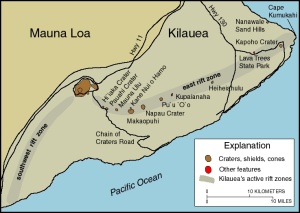

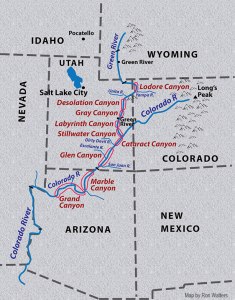

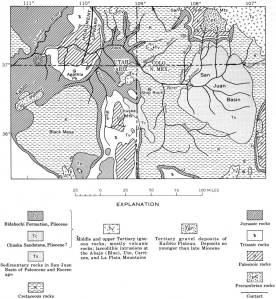

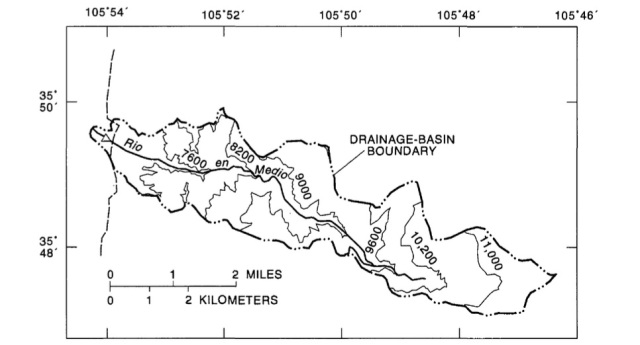

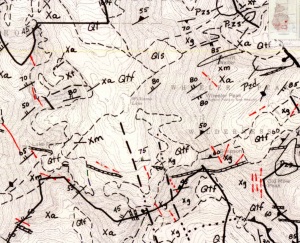

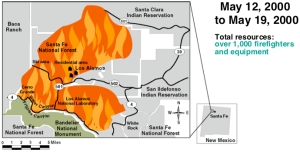

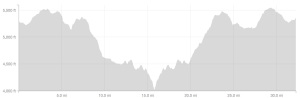

The course of the 50 km, complete with the lost spur. The course descends from the Ski Valley down the drainage of the Rio en Medio, skirts the alluvial foothills above Tesuque, and then climbs back up to Tesuque Peak. Mileage posting help to locate discussion in the text.

About 40 runners toed the line for the 50 km race at 7 am. I had run on all the trails that the course covered in the past, so I knew we were in for a long day. However, despite the familiarity with the trail network, I quickly fell into the pack mentality once the exclaimation of “GO” was shouted by the Race Director. The course loops around the Ski Lodge, and after about 1/2 of mile joins the Rio en Medio trail. A short distance after joining the trail, the actual Rio en Medio is visible, and everyone at the back of the pack settles in at a 12 min/mile pace realizing it will be a long day. Only a few hundred feet into the trail run there is a trail split – on the right hand side is the Rio en Medio trail, and on the left is a branch of the Windsor trail. Everyone in front of me turns left (it was marked with flags, but the flags for the half-marathon course). I am oblivious to the wrong turn, but immediately begin to question whether I have early onset Alzheimers. The trail is nothing like the Rio en Medio I thought I knew – instead of a steep descent along a very rocky trail (the rocks are from a glacial outflow), it is a sinuous up-and-down smooth single track. After a mile many people begin to realize something is wrong, and a group of us stop and discuss the discrepancy in direction and trail markings. I whip out my Gaia app on my iPhone, and sure enough we are already a mile off course! I can only explain this by hiding my geoscience background, and mumbling that I am a “manager”. About a dozen runners cut back to the hiway and run back to the beginning of the Rio en Medio trail, and start the descent again. It ends up that we did an extra two miles, but in the scheme of events, it is just a tiny diversion!

Dave Zerkle along the Rio en Medio trail after dropping about 1,500′ in elevation from the start line. The river flows a well defined canyon for about 6 miles.

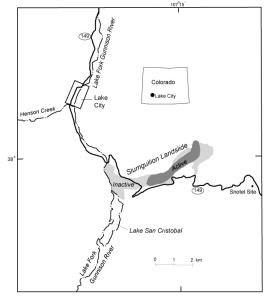

Rio en Medio is one of three perennial streams that drain the high country around Lake Peak; Rio Nambe, Rio en Medio and Tesuque Creek (which has two branches). The Rio en Medio is quite modest by most standards, but in New Mexico any perennial stream is a major asset! The mean annual runoff for the stream is 1,740 acre-feet (the discharge from the Colorado river is about 20 million acre-feet). Northern New Mexico has experienced a wet monsoon in 2016 (started late, but July and August were robust!), and the stream crossing along the trail result in wet feet.

The Rio en Medio drainage basin. The first 6 miles of the course follows the Rio from 10,200′ elevation to 7,600′ elevation.

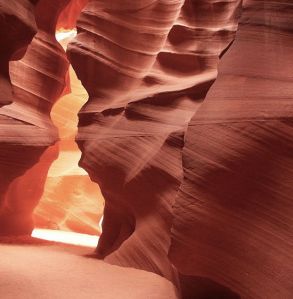

Around mile 5 in the race the canyon narrows and there a a number of waterfalls. This is a truly beautiful section of the race, and does not belie the long climbs to come.

One of several waterfalls along the Rio en Medio. The water has carved a smooth shoot in the Precambrian metamorphic gneiss.

We arrive at the first aid station after running for 1hr and 50 minutes; the mileage is 7.76 miles, and even though we have descended 2,500′, the trail is still cool and in the shade of forest growth. However, after only a few more miles, the trail begins to zig-zags through Pinon-Juniper forest with its sparse tree spacing and low growth. It is now mid-morning, and instead of the temperatures being in the mid-40s, they are in the high 70s.

Dogruel and Zerkle running along a short section of road into Aid Station 2. No one can carry enough water for this kind of running – thank goodness for aid stations!

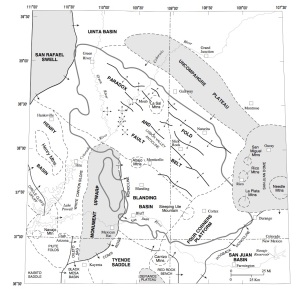

Aid station 2 is only 4 miles from where the course leaves the Rio en Medio, but I end up drinking both my bottle of water in that hour long ramble. Every aid station in the Ultra Santa Fe is incredibly well stocked (and each is different) and manned by helpful volunteers. The trail now is on the alluvial apron derived from some 25 million years of the Rio Grand Rift slowly opening up, and filled by the erosion off the Sangre de Cristo mountains. The rocks that are visible are round cobbles, no two looking alike. It makes for sort of boring running – but I still manage to trip along the trail at mile 14, cutting my knee, right wrist, and my cheek just below my right eye. It was one of those falls that looked worse than it felt, but a powerful reminder that running along a trail requires full attention. I tend to have an active imagination, and get lost in thoughts. When I tripped I was thinking about the North Korean nuclear test the day before. My slightly blackened eye was a gift from Kim Jong-un.

After my stumble my pace begins to falter. The fall probably only has a little to do with this – my longest run since the San Juan Solstice in June has been 17 miles, and I have been on a restrict to keep my runs under 4 hours in duration (note – the limit on the time out on a run does not easily translate to a distance. On steep terrain 4 hours might only be 10 miles!). I urge my team mates to power ahead, and assure them that I will finish even if I am slow. However, they will have nothing of this blatant attempt by me to truly secure the title of DFL.

The view towards the west at about mile 16. The distant mountains, about 30 miles away, are the Jemez and the Valles Grande. Home. Los Alamos sits on the eastern flank of the giant volcanic complex.

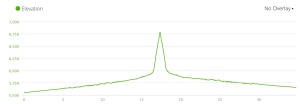

We roll into Aid Station 3 at about 4hrs 30 minutes. The aid station is the low point of the course (elevation wise — spirit wise the low point was still to come!), and is at the Lower Windsor trailhead, only a short distance from the paved road back up to the ski hill. The elevation is 7,200′, and for our day, this is the halfway point in the race (17.5 miles). We have 15 miles of uphill ahead of us to climb a little over 5,000′.

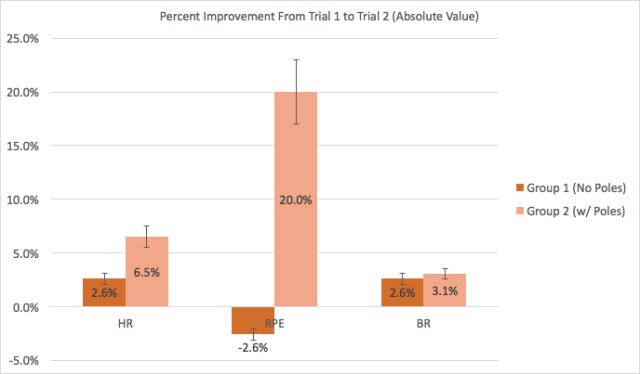

The long climb means that we all take out our trekking poles. Over the last couple of years I have learned that trekking poles dramatically improve my climbing. There are many testimonials to the power of poles, but surprisingly little scientific research into how much poles help. I have found three studies in the biomechanics of pole use; the best study was done in 2010 with a small control group (Trekking Poles Reduce Exercise Induced Muscle Injury during Mountain Running, by Howatson et al.). The control groups ascended and descended steep mountain grades with and without poles, and the researchers concluded that “When hiking uphill at significant grade, under significant load, trekking poles increase efficiency by approximately 10% and decrease perceived effort by 20%.”

The effect of trekking poles. Use of trekking poles increases heart rate (so can tire you out faster) but dramatically improve speed, and something called “relative perceived effort”.

Using trekking poles is an art – it allows you to transfer workload away from your legs to your arms and shoulders, which can decrease your overall level of fatigue. However, using your arms tends to increase your heart rate, so you do use more calories/mile. Further, unless you practice with poles a runner’s cadence tends to slow (and your arms get really tired over 10s of miles!). Our pace with poles as we climb the Big Tesuque Creek is steady, but pretty slow. This slow pace is actually great for observing rocks…within a mile I find a wonderful boudinage.

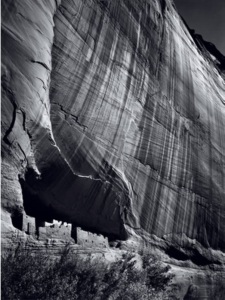

Stretching of a quartz rich band within a gneissic boulder. The stretching pattern breaks up the quartz band into sausage-shaped boudins.

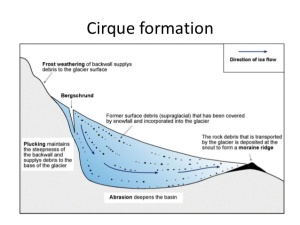

Some 1.5 billion years ago this boulder – more correctly, the formation that this boulder would came from — was subjected to extension. The extension broke apart the bands within the rock; think of pulling a thick roll of dough. This boulder is one of the reasons I like to run in the mountains! Only a short distance later I discovered another treasure – glacial striations!

A medium sized boulder on the side of the Big Tesuque drainage that shows glacial striations. The groves, which run from the upper left of the photo to the center right, are scares from moving ice that was on the Sangre de Cristo mountains 12,000 years ago.

Glacial striations are scratches cut into bedrock by what is known as glacial abrasion. As the ice of a glacier moves down hill it carries debris – rocks of all sizes – and this debris is dragged across the bedrock leaving gouges. I had heard about glacial striations near Lake Peak, but never have been able to find any. I am not certain where grooves carved in the rock pictured above occurred; it is possible that it was far up the mountain, but the boulder had tumbled down to its present location. No matter – the Ultra Santa Fe was getting really interesting! Which was probably a really good thing. By the time we pulled into the 4th Aid Station at Borrego, I was getting quite tired. Mile 22.5, and only 1/3 the way up the hill.

Borrego is just off the paved road up to the ski hill, and thus was well stocked. Better that “well stocked”. There was a platter of bacon, a bowl of sliced avocado, ice cold coca cola, and for my running partners, an assortment of beers. Dave Zerkle was particularly fond of the chocolate porter. This aid station deserves to be in the Ultra Trail run hall of fame. I could easily have stayed there for an hour. Non-trail runners don’t understand the attraction of bacon after long hours on the trail, but the combination of salty crunch and nothing sweet is refreshing. By 6 or 7 hours in a run I can’t really eat much because my stomach just does not want to be bothered. However, bacon can go down…..

After we left the aid station we had a short climb and then a steep descent. It was short, but it was enough to really aggravate my left knee. This knee is about the last “natural” joint I have left in my legs. My artificial joints always feel fine, but my left knee is long overdue for replacement. My knee began to swell – I can control this with advil, but only so much. I knew I could finish the run, but it was going to be slow and painful. I urged the Daves to trek on without me. However, they took turns rotating to pace me. I was both a bit embarrassed and extremely grateful for the friendship. They made the last 10 miles doable – actually more than “doable”, they were enjoyable. I can’t thank them enough for what they did.

Approaching tree line on the Aspen Vista trail. Only a few miles to go from here.

Aid station 5 is at the Big Tesuque Camp ground. Here we found out that dozens of people behind us had dropped out of the race (and others were dropping out at this aid station). It seemed that we might be the last ones left! Only 8 miles to go, I decided not to stop at the aid station and continued on ahead of my companions. I knew they would catch me, but I did not want to “freeze” up. I have done the climb up along the Aspen Vista trail to the top of Tesuque mountain many times. The familiarity of the trail was reassuring – although it also meant I knew exactly how much longer I had to go before I finished.

The last little climb until the top of the mountain. It the background you can see the treeless peaks of Santa Fe Baldy (on the left) and Lake Peak (on the right). The last aid station was at mile 33….still 2 miles to go, straight downhill.

Progress on the climb was slow, but very steady. However, when we got to the top, and I realized we were more than 10 hours into the race and I was stunned. I expected to finish in about 9 hours, and here we were at the top of the mountain, with two difficult miles ahead of us. Those two miles meant a 2,000′ drop. Sounds like it should be fast – and would be if it was the beginning of the race. However, feet are tender, legs are shot, and it is just tough to run. We began the descent knowing that we had locked up the DFL title, so all the pressure was off. We did find some interesting rocks along the way down.

Dave Dogruel touching what has become the Team DFL totem. This is a spectacular migmatic boulder could last 1.7 billion years, so we could last another mile.

We come across an absolute textbook example of a migmatite – a mixture of metamorphic and granitic intrusions. This became our totem – a good luck charm. The Precambrian gneiss, black and sparkly with biotite, had been partially melted and recrystallized after the quartz had fractionated out. Then the rock was stretched, making for a wild pattern.

About 300 yards from the finish line the sleepy volunteers that had been waiting for the last runners were awoken, and began to cheer us on. Really. When we crossed the line we had been on the course for over 11 hours. It was a long day – but I was thankful for a great adventure, and even more joyful for the friendship I have with my fellow runners.

A Nice Way to End

I have run 25 different trail ultra races. I have run them in deserts and mountains; in snow and heat. But, I have never had a race like the Ultra Santa Fe. It was hard and beautiful. But it was also my last before I get my left knee replaced. I am hoping to have surgery complete in the first week of January, and it will take me a year before I am running long distances again. Who knows what 2018 will bring? I am thankful that I got one last wonderful race in – even if others will scoff at the time, it was one of my favorites. Looking forward to recovery and continuing the journey!

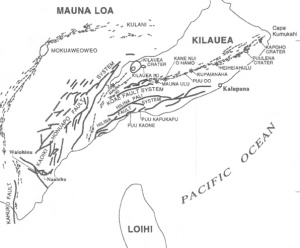

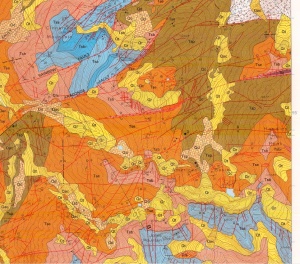

![Geologic map of the State of Hawai'i [Plate 8: Geologic map of the island of Hawai'i [scale 1:250,000]]](https://wallaceterrycjr.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/hawaii_geologic_map_1000_0.jpg?w=262&h=300)