It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, Charles Dickens, in A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

Mineral Collecting has evolved tremendously in the last 65 years. Many collectors bemoan the passing of the “golden age” when spectacular mineral specimens were available for purchase. However, in terms of “classics”today is the true golden age (all thumbnail figures can be clicked for full-sized images).

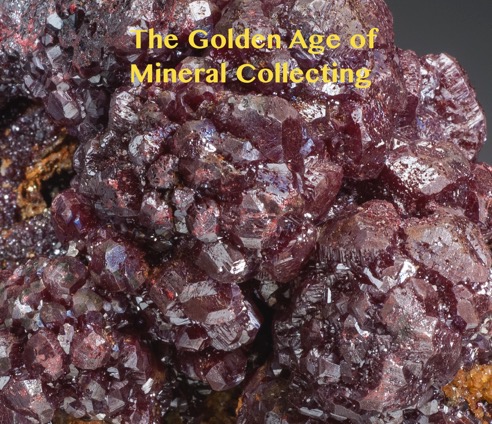

In 1798 Thomas Malthus published his An Essay on the Principle of Population and postulated that catastrophe for mankind was inevitable because population growth is exponential and life essential resources (such as food and water) tended to only grow arithmetically. This simple essay gave rise to a school of gloom and doom, Malthusianism, that has been applied to everything from oil production to luxury items; basically, in a world of fast growing population the demand for commodities will eventually outstrip the supply, and the scarcity of the resources will lead to conflict and ultimately a decimation of demand. However, in the two centuries since Malthus first pinned his thoughts on the clash between supply and demand, the concept of “catastrophe” has been mostly avoided because the same demand that made resources scarce spurred unimaginable creativity and innovation. Between 1800 and the start of the new millennium the world’s population increased 6 fold, yet agriculture increased 10 fold! Many more people, and even more food – and the supply vs demand dynamic was tipped on it’s head.

Malthusianism — population and demand grows exponentially, while supply of resources increases arithmetically. When demand exceeds supply new dynamics happen – perhaps disaster, or perhaps innovation.

It seems a bizarre reach, and perhaps even a non-sequitur, to reference Malthusian theory in a discussion of the “golden age” of mineral collecting. However, the parallels with “peak oil” predictions and the demise of the modern mineral production of truly fine specimens are surprising. Since 1980 the number of significant mineral specimens discoveries is extraordinary; Bunker Hill pyromorphite, Sweet Home rhodochrosite, Red Cloud wulfenite, Milpillas azurite (and other secondary copper minerals), Fresnillo stephanite, Merelan tanzanite and the incredible gemstone minerals from Pakistan along with the flood of minerals from China. Never before has the quantity of high quality minerals been remotely like it is today.

There are many reasons why Malthusian thinking has failed in predicting the dynamics of the mineral collecting hobby, but mostly it is a change in what economists call the demand relationship. Although there has always been a supply-demand relationship in mineral collecting, the foundations for that relationship changed as high-end mineral specimens became “works of art”. University of Chicago economist David Galenson likes to use the career arc of impressionist Paul Cézanne as an exemplar for the art market. In 1895 Cézanne had his first one-man show in Paris, and sold a single painting for 400 francs. A painting that did not sell in this show was later bought in 1899 for 4,400 francs – a tenfold increase in 4 years! In 1913 a Cézanne work sold for 25,000 francs, and in 1925 a painting was sold in auction for 528,000 francs. What changed in those 30 years? Certainly not Cézanne — he died in 1906. Some might argue that Cézanne’s work was simply unappreciated when first viewed, but a more nuanced analysis suggests that a very small number of art collectors were influenced by an even smaller number of art dealers to view the painter’s work as an absolute essential “to have”. Passion – probably influenced by dealer manipulation – drove fierce competition.

The mineral collecting hobby now has the same drivers as fine art. There are many rumors of individual mineral specimens that sell for several million dollars; “I could have bought that azurite for 100 dollars 10 years ago” it has become an old saw for long-time collectors. There is a community longing for years past when a collector of modest means could build a fabulous ensemble of minerals. There is a malaise that a “golden age” has passed, and mineral collecting is in a death spiral. However, the very fact that there is a “minerals are art” market is probably why there are more how quality specimens than ever for sale. This truly is the golden age of mineral collecting.

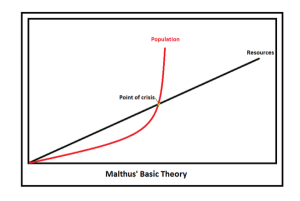

The Tucson Gem and Mineral Show began in 1955, and help span a “golden age” of mineral collecting that orbited around mineral clubs and annual shows. The TGMS show was in the quonset hut pictured above between 1955-1971. Humble beginning for a show that now has special exhibits and displays that are valued at 100 million dollars or more.

The First Golden Age: The Rock Hounding 50s and 60s

Mineral collecting – as a hobby, profession, scientific endeavor – has been around for at least 500 years. Wendell Wilson wrote a fabulous tome on the origins of collecting, The History of Mineral Collecting, 1530-1799 in 1994. “Collecting” coincided with the rise of science applied to mining, and Georgics Agricola’s De Natura Fossilium published in 1546 is considered the first modern textbook of mineralogy. Although there are some exceptions, the first 350 years of mineral collecting was dominated by the gentleman naturalist, and specimen quality was not as important as documenting topographic mineralogy. By the end of the 19th century there were scores of serious mineral collectors in the US (and even more in Europe) – mostly rich business men — and minerals dealers became a real profession. However, in the US the most important event in the later half of the 19th century that changed mineral collecting was the rise of high education. Hundreds of universities and colleges sprung up across the nation, and geology was taught in nearly all; remarkably, all these new colleges sought to acquire geology collections, including minerals. In response to demand, companies like Ward’s (Ward’s Natural Science was founded in 1862 by Henry A. Ward) mass marketed minerals, and the “common man” could own specimens from around the world. This spawned mineral clubs – The New York Mineralogical Club was founded in 1886, the Philadelphia Mineralogical Society in 1892, and by 1900 there were at least 2 dozen amateur groups promoting mineralogy. These societies had a tremendous impact on a generation of scientists; one of my favorite stories is the connection between Linus Pauling and J. Robert Oppenheimer (all stories come back to Los Alamos…..) – they were both mineral collectors! In fact, Oppenheimer gave a several hundred specimens to Pauling when he was at Caltech, and in turn, Pauling gave many of these to his son-in-law, Barclay Kamb, who later became the head of the Earth and Planetary Sciences department at Caltech (he was the department head when I was a student there in the 1970s).

Quartz crystals originally in the Oppenheimer Collection that were given to Luis Pauling. Photograph by Anna Wilsey.

By the late 1930s there were at least 120 clubs in the US, and “rock hounding” was a popular past time. However, it was with the end of World War II that saw an explosion in rock hounding; the hobby literally swept across the country, and by 1947 there were at least a thousand clubs. The American Federation of Mineralogical Societies (AMFS) was founded in 1947, and club gem and mineral shows became common place. One of the most influential of these clubs was the Tucson Gem and Mineral Society (TGMS) which was founded in 1946. Tucson was an international center for mineral exploration, and the University of Arizona had strong academic programs in economic geology and mining engineering. There were more than a 1000 mines – active or abandon – within 100 miles of Tucson, and this was a collectors paradise (anecdotally, when I graduated from Caltech I chose to take a position at the University of Arizona based on this “center of the mineral universe” – it certainly was not the center of theoretical and computational geophysics). In 1955 TGMS launched its annual show (nine dealers, but more than 1500 attendees!). Soon the TGMS show aggressively moved to the national stage – and attracted exhibits from museums like the Smithsonian Institution – and by the mid-1960s was attracting an international cliental. The 1970 were halcyon days for mineral collecting – thousands of colorful minerals were pouring out of Mexico, and the TGMS show was a perfect market place. This is what most collectors think of as the “golden age”. One of the factors that contributes to the nostalgia was the modest prices charged for minerals – it was a mom and pop enterprise catering to a broad spectrum of collectors.

The TGMS show changed the mineral collecting hobby – it became big business. Satellite shows proliferated, including the hotel room collection of dealers that set up at the Desert Inn. This was the front end to the transformation of mineral collecting as a populist hobby to high art.

The dramatic growth the mineral collecting enterprise naturally became stratified. The “best” minerals, especially those that were colorful, became much more expensive. In addition, the concept of a market for minerals that paralleled the market for art pushed this segregation even further. By the late 1970s there were mineral dealers in the TGMS show that only “dealt” with high end material; these dealers would sell individual specimens for more money that most of the mom and pop dealers would make during the entire TGMS show. It was the Malthusian end – demand crushed the supply side of the equation. Further, it seemed advances in mechanized mining, solution extraction, and exploration of low grade ores meant that the flow of collectable minerals was slowing to a trickle.

Much grumbling was heard in the late 1970s that the mineral collecting hobby was “over”. Purchasing high quality specimens was becoming out of reach for many collectors, and large number of the collecting localities in the US were being reclaimed or closed to the causal rock hound. However, the very driver that caused this grumbling – money – was allowing collecting to be done on a commercial scale. Collecting contracts were profitable in some large active mines, and the potential to realize profits began to entice wealthy collectors to invest in specialty mining: the Sweet Home Mine rhodochrosite and Red Cloud wulfenite mining endeavors would not have happened without a market for million dollar rocks. In the mid-1990s dealers began to market on the internet – it was an innovative way to reach remote customers, but it also had the remarkable effect of democratizing the pricing of minerals. Miners in Bolivia could actually see how much a dealer in the US was asking for the vivianite specimen the miner had sold to the dealer a month ago. A new supply-demand relationship in mineral collecting was born.

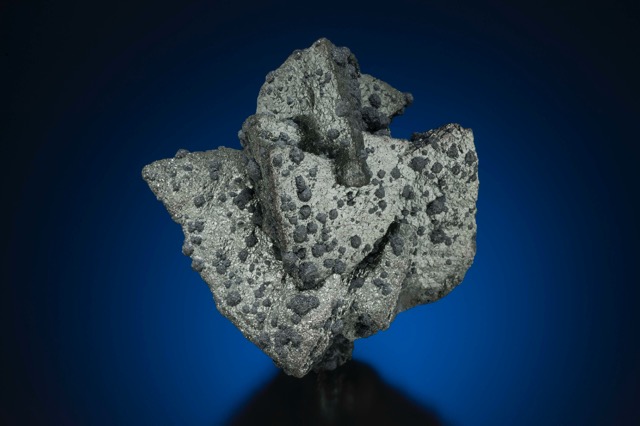

Silver in friable quartz, Andaychagua Mine, Peru (photograph by Jeff Scovil). The specimen is 5.2 cm tall, and shows a plate of spinel twins; mined in May, 2015.

Today’s Golden Age – At Least for Silver Minerals

Complex cluster of acanthite crystals, 3.2 cm high from the Mina La Cata, Guanajuato, GTO, Mexico (Jeff Scovil, photograph).

Guanajuato is located 475 km northwest of Mexico City, along the “silver channel” a string of incredible silver districts running along the spine of Mexico. In 1548, a group of ore haulers was returning to the recently discovered silver camp of Zacatecas after delivering their load to Mexico City. The haulers decided to camp beneath a rock outcrop that resembled a frog – the name Guanajuato is said to be a Spanish pronunciation of the Tarascan Indian word for hill of frogs (Martin, 1906). A little prospecting uncovered a vein of silver, and a claim was staked on one of the world’s greatest mining camps. Over then next 475 years Guanajuato would go through periods of boom and bust; the booms were extraordinary! In the 18th century Guanajuato accounted for two thirds of the world’s total silver production. In 1906, Englishman Percy Martin wrote a promotional book call Mexico’s Treasure House (Guanajuato), in which he extolled the virtues of the silver district: “The silver mines of Guanajuato differ from most other mines in the world inasmuch as there is nothing conjectural nor problematic about them”. Hardly true, but there is nothing conjectural about the fact that for 450 years the district has supplied unsurpassed mineral specimens.

Basic geologic map of Guanajuato from Wendke, 1965. The Mina La Cata is located between the Valencia and Mellado.

During the summer of 2014, and again in the spring of 2015, very fine spinel twinned silvers were found at the Andaychagua Mine, in the San Cristobal District of Peru. The San Cristobal District has long been known for silver minerals, but the new find are the best herring bone silvers to be mined since the Batopilas, Mexico silvers recovered in the 1980s.

Multiple plates of spinel twinned silver from the Andaychagua Mine Peru. The specimen is nine cm tall. Jeff Scovil photograph.

The San Cristobal District is located in the Cordillera Occidental about 120 km east of Peru and the first mines in this region were recorded in the 16th century. The region has a rich history of producing silver-bearing mineral specimens and some fine spinel twins of native silver (from the San Cristobal Mine) in a crumbly siderite matrix were on the market in the mid-1980s. The Andaychagua mine is one of four (the other three being the San Cristobal, Ticlio and Carahuacra) in the district that are active, and is presently owned by Volcan Compañía Minera S.A. (acquired in 1997). The annual silver production from the district is about 250,000 kg – however, specimens for collectors have been rare for the last 20 years.

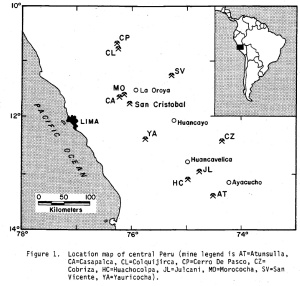

Location of the major mining districts in Peru. San Cristobal is a mountainous district with an average elevation of approximately 14,500′ (map from Bartlet, 1984).

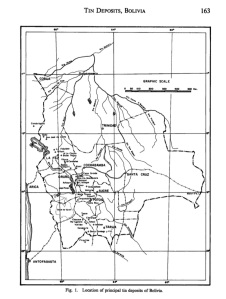

The Machacamarca District, also known as the Colavi District, is located in the Bolivian tin belt, a chain of related mineral deposits that extends nearly 1000 km north-to-south along the eastern Cordillera of Bolivia. The northern part of the belt is marked by Suko, and the southern end is Pirquitas in Argentina. The world’s most famous silver deposit – Cerro Rico in Potosi – sits in the middle of the tin belt. Colavi is only a few 10s km north of Cerro Rico – but those few km are across the most rugged mountainous terrain in the world.

The mine of the Bolivian Tin Belt. In the center is Potosi, home of Cerro Rico. Machacamarca, Colavi is located due north of Potosi.

In April of 2015 a significant find of freibergite crystals were recovered from an obscure mine identified as the Melgarejo Mine. Numerous geologists that work in the area scoff at the locality – they don’t doubt Colavi, but have never heard of nor seen the Melgarejo Mine. Mariano Melgarejo is a Bolivian historical figure of some considerable ill repute – he give a significant portion of eastern Bolivia to Brazil in the Treaty of Ayacucho in exchange for a magnificent white horse, and in 1870 ordered his troops to march to Paris to protect France from an invading Germany. Nevertheless, the freibergite crystals are certainly the largest ever found. It is difficult to tell the difference between friebergite and tetrahedrite (that carries some amount of silver), and many specimens labeled freibergite turn out to be the much more common tetrahedrite. The specimen shown below is the one of the very best found, and I personally checked the structure to confirm its identification. Considering that freibergite has been identified from hundreds of localities since the late 18th century, the fact that “world’s best” now appear is remarkable.

Freibergite crystals, 7.2 cm across (Jeff Scovil photograph). The reputed locality is the Melgarejo Mine, Machacamarca, Colvai, Bolivia. “Reputed” because some have questioned whether the actual locality was obscured to preserve a source.

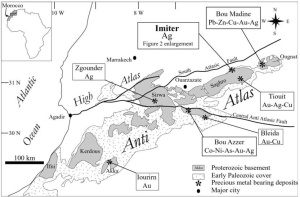

The Imiter deposit is located in the Anti-Atlas Mountains, Morocco, northern Africa, and it is one of the largest silver deposits in the world. Imiter has been producing wonderful collectable specimens for several decades; these include octahedral acanthites, dyscrasites, various silver-mercury amalgams, some of the world’s best xanthoconite, and is the type locality for imiterite. Proustite is well known from the mine, but most of the crystals have been small. The specimen below is a large cauliflower like clump of crystals (the specimen weighs just under 3 pounds!) with individual crystals that are up to a cm across and several cm tall. It is impossible to know for sure when this specimen was recovered – it is clear that it was smuggled out of the mine, and passed through local merchants before coming to the US in late 2014.

13 cm cluster of proustite crystals from Imiter, Morocco (Jeff Scovil photograph). This small cabinet sized specimen is solid proustite, and contains individual crystals to 1.8 cm on a side. The luster, and deep vermillion color, and overall size make this a modern “classic”.

Although this is hardly a “classic” proustite as compared to a sharp dog’s tooth from Charnarcillo or individual cherry red crystal from Schneeberg, it is an amazing specimen. The Imiter Mine had a capacity of 300,000 metric tons per year (t/yr) of ore and surely will continue to produce interesting specimens.

Metal mines of the Anti Atlas mountains in Morocco. Imiter is one of the largest silver mines in the world, and is a large open pit.

When will the Golden Age Wane?

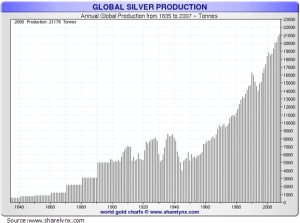

Malthusian theory would predict that demand will outstrip supply in the future – maybe the near future. But mineral collecting is not dead, and in fact there is as much evidence based on the last 30 years that there will even more high quality specimens exchanging hands for decades to come. Why is Malthusian theory is wrong? Because demand for minerals – both as a commodity and as a collectable – is higher than it has ever been, and the world is responding. More mines, more mining, and more money in minerals.

Global silver production – looks just like the global growth in population! Each and every mine has the potential for specimens and even though historic localities are exhausted, new horizons are bright.

It is certain that the market of “art” will be what mineral collectors will have to deal with in the next quarter century. If history of the art markets are predictors for minerals, there will be periods of malaise; but even during these periods the assessed worth of classics had an average annual escalation of several percent. This leads to another question – where the heck do all these wealthy people come from? Again, there are detailed studies of the art market, and one of the alarming (alarming if you are a collector, perhaps enticing if you are a dealer) lessons learned is that globalization will dramatically increase competition at the highest end. However will mineral collecting evolve with a very stratified market? That experiment is being played out in real time, and I hope for “niche markets” to develop – but that has not happened yet. Hold on to your wallets, the golden age squeezes…….