It was soon after I began collecting stones, i.e., when 9 or 10, that I distinctly recollect the desire I had of being able to know something about every pebble in front of the hall door–it was my earliest and only geological aspiration at that time, Charles Darwin in his autobiographical notes.

Sunset on the Cordillera del Paine as viewed from the south across Lago Sarmiento (picture taken 12/29/16). An amazing mountain range carved of granite crafted by the ice of glaciers.

The Cordillera del Paine is an awe inspiring mountain range. Although the Paine massif is modest in areal extent, it simply defies gravity. Towering cliffs of white granite seem to magically jump out of the gently rolling hills of the Patagonia steppe. I first saw a picture of the Torres del Paine – three impossibly slender yet massive towers of stone – in a National Geographic magazine in the 1960s. The imagine was stunning and stayed with me for 50 years. When I was 20 I imagined I would climb the towers; when I was forty I imagined I would scale the cliffs to the base of the towers; now that I am sixty I am thrilled just for the opportunity to trek to the glacial lake beneath the towers and drink in the perfection of nature.

I worked extensively in South America in the 1990s thru 2002. Along with a few academic colleagues and a legion of outstanding graduate students, we deployed seismic stations across the Andes to record earthquakes. These seismograms allowed us to image the structure of this remarkable mountain range, and help understand the dynamics of mountain building. I worked in Bolivia, Peru, Chile, Argentina and Venezuela. Despite all the time in the field in South America, I never made it to Patagonia. It was one of my great regrets; finally this year my wife and I vowed to remedy that regret. We planned a trip to the “bottom of the world” and aimed to visit the Cordillera del Paine. It is hard to describe the exhilaration of seeing the ragged mountain peaks, the white and blue ice of moving glaciers, and the rollings caps of waves created by the ceaseless winds blowing across lakes to a non-geologist. Everyone thinks these things are beautiful, but to me they are more – they are are spiritual. They are the art work of a dynamic planet.

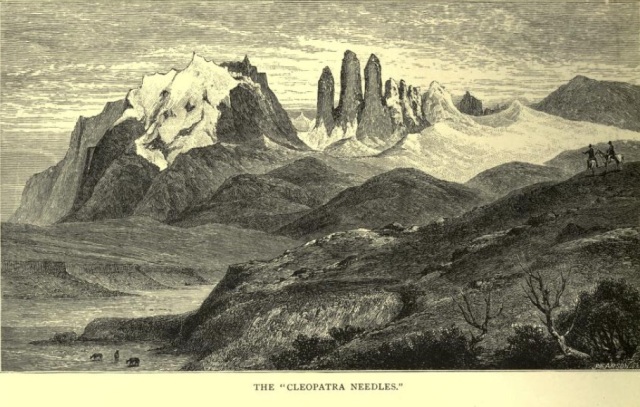

Torres del Paine (the Towers of Paine) as sketched in Lady Florence Dixie’s book Across Patagonia (1881).

The first European account of the Cordillera del Paine was contained in a travel novel written by an amazing Scottish woman, Lady Florence Dixie, Across Patagonia. Lady Dixie was first and foremost a feminist, and then an adventurer and writer. Her brother, Lord Francis Douglas was on a team that made the first successful ascent of the Matterhorn in July 1865 (although he died on the descent – a lesson that all mountain climbers learn; the job is to get to the bottom not the top). In 1878-79 Dixie traveled across Patagonia – she chose this adventure because “few European men, and no women had ever visited it”. After traveling many weeks across the wind swept Pampas she was startled at the majestic rise of the Andes. Her description upon catching her first glimpse of the Cordillera del Paine: “From behind the green hills that bound it rose a tall chaine of heights, whose jagged peaks were cleft in the most fantastic fashion and fretted and worn by the action of the air and moisture into forms, some bearing the semblance of delicate Gothic spires, other imitating with surprising closeness the bolder outlines of battlemented buttresses and lofty towers….three huge Cleopatra peak rising from out of the snow glaciers far ahead of us.”

Cleopatra Needles, 140 years after Lady Dixie visited (photograph 12/29/16).

Dixie’s description resonants with me. It also causes a few pangs of jealously. What it most have been like to see something such majestic landscapes without expecting it? Discovering the impossible! Our trip was planned to see both the great granite spires and the glaciers that relentlessly carve the rock away. Of course, unlike Lady Dixie, we had expectations on what we would see. However, “seeing” the Cordillera del Paine in pictures is nothing like physically standing in the shadow of a 3,000 foot shear cliffs. The long journey to the bottom of the world was amply rewarded.

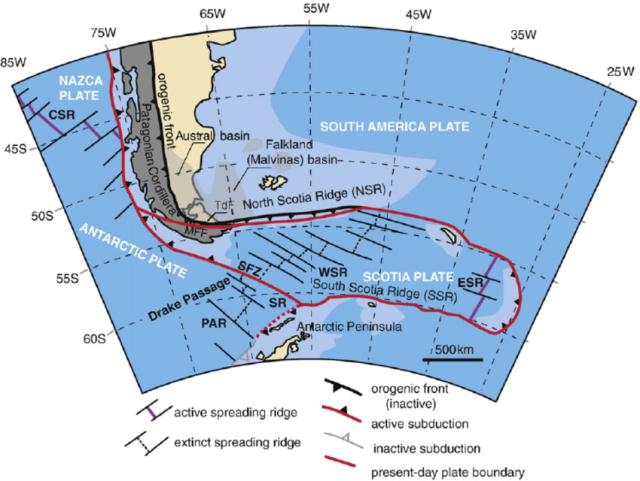

General tectonic setting at the bottom of the World. The bulk of South America is shaped by the interaction of the South American continental block and the subduction of the Nazca Oceanic plate beneath it’s western margin. In the far south the tectonics are far more complex and have evolved significantly in the last 25 million years.

Geology at the End of the World

The story of the Cordillera del Paine is both short (in time) and sweet. But, it is different than that of the rest of the Andes, and that makes it history complex. The Andes are spectacular mountains that occupy the west coast of South America, stretching nearly 7,500 km from Colombia in the north to Chile in the south. They contain peaks second in height only to the Himalayas; Chimborazo in Ecuador rises to 6,277m, Huascaran in Peru is 6,768 m, Tocorpuri on the border of Chile and Bolivia is 6,873 m, and the highest mountain in the Western Hemisphere, Aconcagua at 6,950 m, marks the boundary between Argentina and Chile. Incredibly deep valleys and impassable terrain break the line of towing peaks, which are often capped with glaciers. In some places the Andes narrow to only 35 km, whereas in Bolivia they divide into two ranges and bound a high-altitude plateau, the Altiplano, which is nearly 640 kilometers (400 miles) across. The imposing mountain chain shapes the ecology of the entire continent by forming a barrier to moisture, which usually travels from the Atlantic toward the west. The peaks trigger enormous rainfall that feeds the great Amazon jungle, leaving little moisture for the incredibly dry Atacama Desert, where decades may pass without measurable precipitation.

Convergence between the continental South American plate and the oceanic Nazca plate gives rise to the Andes; the subduction or consumption of the Nazca plate beneath South America is a violent and spectacular geologic engine. As the Nazca plate descends beneath South America into Earth’s mantle, the sediments, minerals, and rocks carried downward respond to the increasing pressures and temperatures by melting. In turn, the melt rises toward the surface and erupts in spectacular volcanoes.

In southern most Chile the subduction boundary between the Nazca plate and South America ends. There is a triple junction near the Taitao Peninsula; this is the junction, called the Chile Triple Junction (CTJ), and marks the interactions between the Nazca, Antarctic and South American plates. South of the junction Antarctic subducts beneath South America, but at a much slower rate than the Nazca subduction north of the triple junction. This marks a major change in the Andes – and this is the reason Patagonia is “different” than the rest of South America.

The very first geologic map of Patagonia was drawn by Charles Darwin ca 1840. There is no evidence that Darwin actually gazed upon the Cordillera del Paine, but the father of evolution theory clearly understood Patagonia was a very special place.

Charles Darwin visited South America during the 5 year voyage of the HMS Beagle (1831-1835). Darwin wrote extensively on the geology of the continent; On the connection of certain volcanic phenomena in South America (1838), On the distribution of erratic boulders and on the contemporaneous stratified deposits of South America (1841), and a classic book Geological Observations on South America (1846). It is fair to say that Darwin’s geologic insights were not as deep as his thoughts on plants and animals. However, in the preparation of his book he did draft the first geologic map of Patagonia (figure above). This map was never published but is the Darwin archive at Cambridge. Although it is highly simplified, it does capture the broad geology of Patagonia; mountain ranges in the west that have uplifted sediments that had been deposited in a shallow marine basin located in the Atlantic ocean. Most of the exposed geology in Patagonia was created by the history of the CTJ. Around 15 million years ago the southern most section of the Nazca Plate and its spreading ridge were subducted and the CTJ was formed. The CTJ migrated northward to its present location as more and more of the Nazca Plate is consumed.This migration is accompanied by localized intrusions of granitic laccoliths (sheets or domes of igneous rock injected within a sedimentary sequence of rocks).

A view of the great Paine Massif from across Lago Nordenskjol. The white colored rock is the a series of granites injected 12.2 million years ago; the dark rocks are ~100 million old marine sedimentary rocks that “received” the injected laccolith. (picture taken 12/29/16).

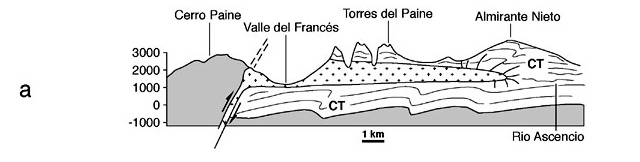

The CTJ passed the area of present day Torres del Paine about 13 million years ago, and ~12.2 million years ago the Cordillera del Paine laccolith was injected into gently dipping sedimentary rocks formed in a sedimentary basin between 60 and 100 mya. There were at least 5 pulses of injection over a 50,000 year interval. The laccolith has an areal extent of 10 x 20 km, and is 1800 m thick at its maximum. This laccolith uplifted the surrounding sediments – it looked like a large bubble on the Patagonia landscape.

A notional cross-section through the Cordillera del Paine. The main intrusion is the sausage shaped unit denoted with “+”. To accommodate the intrusion the sediments folded and faulted.

The intrusive phase was remarkably short lived, and as the CTJ continued its migration north there was no further magmatic activity. Around 10 mya the region of the Cordillera del Paine was probably a broad highlands, with minor peaks. Starting in the late Miocene (~5 mya) the region began to be covered with a large ice sheet, and the erosive forces of ice began to carve the del Paine into to the familiar landscape of today. Interestingly, the first scientific observations about Patagonian glaciations were presented by Charles Darwin who, along with Robert Fitz Roy explored Patagonia 150 km north of the Cordillera del Paine. Darwin postulated that “miles of rock” had been removed by ice.

It is hard for the average person to understand the incredible power of large scale glaciers. In optimal settings glaciers can erode up to 1 m of bedrock for every 1 km of sliding. Given a few million years the persistence of gravity dragging ice across granite, shale and sandstone will carve canyons 1000s of meters in depth. Today the glaciers have surrendered their massive size to a warmer climate. The ice is still the primary erosion element in the Cordillera del Paine, but it is orders of magnitude smaller than it was 20,000 years ago.

Heading up Seno Ultima Esperanza (the sound of last hope) to Monte Balmaceda and glaciers on the boundary of Torres del Paine National Park. The rainbow is created by the constant winds blowing spray into the air (picture taken 12/27/16).

West of the Cordillera del Paine is the Campo de Hielo Sur, or Southern Patagonia Ice Field. This is a massive extra-polar set of glaciers that covers nearly 12,500 square kilometers. The ice field offers the best view of the glaciers near Torres del Paine; traveling up some of the large fjords allows a close up examination of these glaciers.

Serrano glacier on Balmeceda, just south of the Cordillera del Paine. The glacier is in rapid retreat due to rising temperatures. Only 25 years ago the leading edge of the glacier was at the point that this photograph was taken (12/27/16).

One of the most famous glacier at the southern end of the Southern Patagonia Ice Field is Serrano. Serrano is a “valley glacier” that connects the ice pack on the high elevations of Monte Balmaceda, and terminates near the Seno Ultima Esperanza. The valley glaciers are a delicate feature; they depend on air temperature and ice being deposited at the glacier head. Surprisingly, the ice creation is most important feature for the health of the Serrano (and other valley glaciers). A area is surprising arid – the annual precipitation rate at Natales, a town on the Seno Ultima Esperanza, is only 11 inches per year (about the same as Tucson, Arizona). The Serrano is still an impressive glacier, but it is rapidly retreating. The retreat is due doubt related to a rising temperature, but it is also the product of a decades long drought that is thinning the ice field.

Float ice below Serrano glacier, and a great glacial erratic. The rock perched on another rock in the lake are materials that the glacier removed from high up the mountain and when the ice melted left stranded.

The geology of the Cordillera del Paine is one of granite and changing plate boundaries. However, the artistry of the Paine is the handiwork of the ice that has flowed across the granites for millions of years.

Geo-Paparazzi disguised as Trekking

The pictures I saw in National Geographic when I was ten years old made me dream of climbing the Torres del Paine. However, certainly by middle age, I realized I had trouble even climbing a rope, and I was much better suited to hiking and scrambling, so there was never any chance I was going to scale anything like the towers. When I was in my 40s I hiked many high mountains in the Andes including some 6000m peaks, but they were not technical (one of the advantages of climbing in the Andes is that it is possible to get high with persistence and planning, even without much athleticism). When I first was planning my visit to the Cordillera del Paine I had visions of trail runs to the bases of all the peaks I had dreamed of climbing, but in the end, the trip was about simply being able to trek around the stunning geology of Torres del Paine.

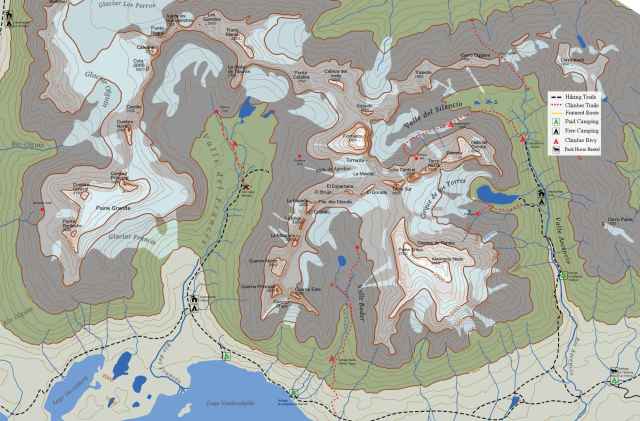

Map of the Paine Massif. The stars are the Torres del Paine (and the glacial cirque below them) in the east, the Cuerno (Horns) in the center, and Paine Grande (the highest point in the Cordillera) in the west.

The verticality of the Paine Massif becomes immediately obvious when you plan a trek. The glacial lake bounding the southern extent of the range has an elevation of approximately 250′; the highest peak, 2 miles north of the lake has an elevation of 9,426′. That massive wall of elevation is a sequence of cliffs isolated by deep valleys. It is hard to get to the higher elevations – the climbs are often technical, and the Park controls access (both for safety concerns, and for ecological concerns). However, simply cruising in the shadows of the towers is an extraordinary experience.

Michelle Hall and I on one of the trails that eventually leads to the Paine Massif in the background, and on up to the Torres del Paine, just out of view on the right of the photograph.

We planned a trek of two days that took us from the western edge of the Paine Massif to a high glacial lake at the base of the Torres del Paine. The weather of Patagonia is legendary; every day often sees bright sunshine, rain, mist with visibility of no more than a few yards, and wind — oh, so much wind. The joy of the weather is that you know it will change (and change back again). We started our trek on the shores of Lago Nordenskjold beneath the Cuernos, or Horns of the Paine. Nordenskjold receives all the melt waters from the mountain glaciers in Cordillera; its milky green color reflects the large sediment content carried from the melt waters. This sediment is the finely ground rock remains caused by the glacier scraping the bedrock. This fine grain material is called “rock flour”.

Looking across Lago Nordenskjold to the horns. On the left is Cuernos Principal, and on the right is Cuernos Este. The contrast between the black of the shales and the white of the granite make this one of the most iconoclastic views in all of geology.

The view of the Horns is breath taking – and almost impossible to capture with a camera. The contrast of a deep blue sky, low white clouds, pale white granite, black sedimentary rock and the green lake water make the view seem artificial. The colors look more like they were conjured by an artist in a painting, than by the subtle hand of nature. The tallest of the horns is Cuernos Prinicipal, and has an elevation of about 8,600′ (or a vertical scarp of 8300 above the lake). As the map at the top of this section of the blog shows that the majority of the great laccolith has been removed by glaciers – only 10 percent of the granite remains. The spectacular view is a dying gasp of a great mountain range.

Salto Grande. A water fall that captures flow from Lago Nordenskjold to Lago Pehoe. The water color of the various lakes depends on how much glacier runoff enters the lake. Green colors mean that there is a significant amount of sediment, or rock flower, from glaciers. Blue colors have little to no sediment.

Nordenskjold lake drains into Lago Pehoe, which in turn drains into Lago Toro, and finally into the Serrano River and on to Seno Ultima Esperanza. Nordenskjold and Pehoe are about 150′ different in elevation; this difference creates a water fall called Salto Grande. The odd color of the water makes for a scenic, and unique, cascade.

The views from the Cuerno group to Torres del Paine are all stunning. In fact, the views inflict soreness in the neck as the head is always looking up! The views also impede the progress in trekking to the east. But the main event is in the east, the climb up to the towers.

The trail to the Torres del Paine. Valle Ascencio. The path from the base of the Ascencio to the glacial lake is about 5 miles. The first few miles are a rocky climb, but then the trail enters a lush forest.

Our climb up to the Torres del Paine starts on day two, and in less than auspicious weather conditions. The morning is misty and intermittent rain, and it is impossible to see the Cordillera. We are hiking with a guide, and he seems to be preparing us for the likelihood that the towers will be invisible even up close. The path is steep, but well traveled and for the first several miles the low clouds and lack of vegetation make the journey tiresome. However, at about mile 5 we enter a dense forest of Patagonia birch trees. These trees are a remarkable hardwood, and are coveted for their longevity in construction (hundreds of years!).

Lush forest along the trail – the tree is lenga (Nothofagus pumilio), a variety of birch.

The last 1 km of the trek to the base of the towers is a scramble up the boulder field associated with the mountain glacier connected to Torres del Paine. The 1000′ climb is rewarded with an extraordinary view – and a sudden parting of the low clouds to allow the sun to shine in.

The last km of the trek up to the view of the Torres del Paine is a scramble up the outwash from the glacier that carved the towers. The elevation gain is about 1000′, and the tough climb makes the reward of the view even more sweet.

The elevation of the small glacial lake below the Torres del Paine is about 3200′. The tallest of the towers has an elevation of approximately 8200′ (the exact elevation of the towers remains in dispute, and no accurate survey has been conducted). 5000 feet of granite relief! Although the weather cooperated, pictures of the three towers simply do not do justice to the stand of rocks. They are unlike anything else in the world – true spindles that are nearly vertical. Torres del Paine translates to Towers of Paine, where paine means “blue” in the native Tehuelche language. The blue is in reference to the apparent color of the towers, especially in late afternoon. On a cloudy day it seems a stretch to call the granite blue; but the color is not the compelling feature.

The view of the Torres del Paine on December 30, 2016 at 11 am in the morning. For a brief period the clouds opened up and presented the image of the fierce teeth in the jawbone of some ancient dinosaur.

I took approximately 1 million pictures of the towers. Strangely, they all looked the same once I got back to the hotel and looked at them. I struggled with the enormity of the landscape. The south tower, the one on the left in the photo above was first climbed by Armando Aste in January 1963. Climbs of the towers remain some of the most difficult in the world, and attract the best alpinist every January. In 2015 two Chileans and an Argentine climbed all three towers in three days!

A look back toward the Torres del Paine near the end of the trail.

Reluctantly, after an hour of picture taking and tasting the water in the lake (glacial runoff!), we had to leave and trace our path back to catch a ride to the hotel. The journey down was rainy – the clouds began to move in, and we were reminded how lucky we were to have summited in relative sunshine. Those few hours of trekking up and back to the Torres del Paine made all the difficulties of traveling to the bottom of the world worthwhile.

Flying from Punta Arenas to Santiago we passed over the Cordillera del Paine – and got this extremely rare view given weather conditions and cloud cover. The large glacier is Gray Glacier, and the green lake in the right center of photo is Nordenskjold. The Cuernos Principal is visible to the left of the jetty in Nordenskjold.

What will the future bring?

The Cordillera del Paine is truly a “wonder of the world”. It is small in size – smaller than the Grand Tetons in Wyoming – but nature has conspired to build something that stretches the human experience. About 150,000 people visit the park annually (compared with 2.8 million that visit the Grand Tetons for hiking); roughly 20% of those choose to trek into the interior of the park. The park is strict about staying on trails, and requiring registration and tracking for all visitors. However, it is not the same experience that Lady Dixie must have had 140 years ago. The biggest difference is the retreat of the ice. The glaciers in the Souther Patagonia Ice Field are all shrinking; there has been an areal loss of more than 60 sq km since 1945. The loss of ice is not important for the dynamics of the Cordillera – the glaciers long ago did their work. But the ice is a fundamental part of the spirt of the mountains.

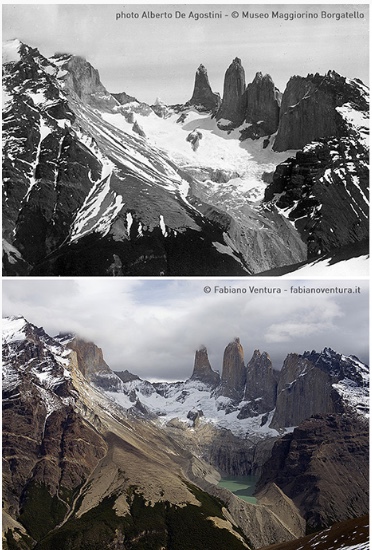

A view into Torres del Paine; the top photo was taken by Alberto De Agostino, circa 1920, the bottom view taken this year by Fabiano Ventura. Although the towers look the same, careful observation will show that the glacier has nearly disappeared, and the glacial outwash has been removed over the last century creating a lake.

This year an Italian, Fabiano Ventura is photographing glaciers in Torres del Paine in the exact location as a Alberto De Agostino, missionary in Patagonia in the early part of the 20th century. The contrast in his images shows the rapid change as the ice departs. Change is inevitable – in geologic terms this change is extraordinary powerful. I don’t know what Torres del Paine will look like in 50 years…so I will return in 2 years after I recover from an new knee replacement. I will be running the Torres del Paine Ultra! (http://www.ultratrailtorresdelpaine.com).

Nice entry, dude! I’m glad you explained the milky green color of the lake and the falls. I would have spent most of the night searching for that had you not explained it. I’m glad you got to see the towers. Maybe the “blue” part translates to the idea of melancholy? Don’t know if Tehuelche has such a euphemism. Travel on, sailor, travel on….

I appreciate your emotional response to the landscape. For someone, such as yourself, who has traveled extensively and worked in landscapes such as these, to *still* feel overwhelmed and awed by what you see… yes, I think spiritual is the right word for it. Thanks for sharing your account.

I never thought about it as being able to be jaded – but your comments got me to think about what I am jaded about; 10,000 dollar minerals people try to sell me, airline delays, and polite politics. thanks for your reminder.

Professor Terry, I’m proud to say that even as a student you were far ahead of me in geological knowledge. Your career is phenomenal! Your 89 year old former teacher. CDW

Mr Wagner – thanks so much for the message. 2 years ago I gave a commencement address and talked about “everyone says you can be whatever you want to be — that is baloney. As the marines say, nothing is given only earned”. In the remarks I talked about opportunities and I talked about taking your geoscience class way back in 1971. Best regards, Terry

A haunting landscape – but haunting in the good way that it stays with one forever. This sounds like it’s been one of those trips of a lifetime!

Global warming, man. Bummer. Thanks for the post, it was different than most travel posts.