The Wilderness holds answers to more questions than we have yet learned to ask, Nancy Wynne Newhall, Ansel Adams biographer

Panorama of the Williams Lake Cirque from Simpson Peak (7/16/16). On the far right hand side of the photo is Wheeler Peak, and the left side is dominated by the ridge connecting Simpson Peak with Sin Nombre (all a class 4 scramble). The high points of New Mexico. Click on any thumbnail to get a large version of the photo.

On September 3rd, 1964, the President of the United States signed into law “the Wilderness Act”, a profound articulation of societal values that seemed to be at odds with the 200 years of manifest destiny that had driven the country to spread from shore to shore and taming every inch of the land for the “good of man”. The act stated it was the policy of Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness. Wilderness is a highly abstract concept – for some it means a place of danger and darkness, but for others, including me, it is a place where nature and the forces of nature rule supreme, and the imprint of man is superficial.

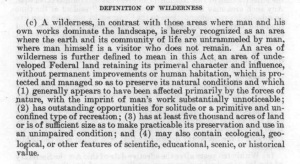

The poetic definition of WILDERNESS from US public law 88-557, the Wilderness Act, passed in 1964. “…where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Running, climbing, breathing high in the mountain wilderness is a special, spiritual joy. Away from the hubbub of humanity – the constant noise of commitments, the stress of conflict and confusion, the muddle of minutia – wilderness allows my mind to clear, and my spirit to lift. I love being alone high on a mountain with the tremendous forces of geology laid bare. Those forces, driven by the steady heat engine of Earth, constantly remake and renew the planet. The landscape tells stories; painted with the brush of enormous time, the rocks and minerals hold the secrets of pressure and temperature. Really, I am not much of a runner or climber, but they are primal acts that allow an individual connection with something that dwarfs humanity.

Fortunately, there are many places in the southwest where it is possible to escape into wilderness. The highest point in New Mexico is Wheeler Peak, which is located in the Wheeler Peak Wilderness area – a fantastic place to experience “wilderness”. The wilderness area is about 20,000 acres, and within this modest tract sits 5 out of the 10 highest peaks in New Mexico. One of the very best “bushwhack” runs in the entire country connects these high points; it is called the Alpine loop, and it is a 12 mile, horse shoe shaped tract that frames a classic alpine geomorphic structure, the Williams Lake cirque. For various reasons I am restricted on how far (or how long) I can run right now, and the Alpine loop is a perfect challenge that gives the full “geology is immense” experience.

Google Earth view from the north looking into Williams Lake cirque. Today Williams Lake is tiny – it is barely visible in the center of the field of view. 11,000 years ago an alpine glacier scoured out the cirque. Snows falling on the high peaks compacted into a glacier that gravity constantly pulled downhill. The rubble the glacier carried with it served as a sort of “sand paper”, and carved the cirque.

Something Old, Something New

The skyline of northern New Mexico is dominated by a narrow chain of north-south trending high mountains, the Sangre de Cristo. The Sangre are a remarkable (and often unappreciated) range; they rise in the north at Salida, Colorado, and terminate to the southeast of Santa Fe at Glorieta Pass. There are 10 14ers in the range which dramatically towers over the Rio Grande Valley which is located to west of the range – in fact, the Sangre de Cristo owe their prominence to the Rio Grande Rift which began to open about 27 million years before the present. As the rift developed, stretching the crust, faults fractured the crust and Sangre were uplifted to elevations thousands of feet above the rift.

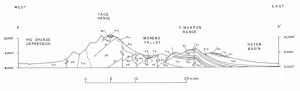

A cartoon view of the Sangre de Cristo mountains viewed from high above Los Alamos, NM. The range is very narrow in the north, and has a much broader expression near Taos. To the west of the Sangre is the Rio Grande Rift.

This uplift exposed rocks that had been deeply buried in the Earth’s crust, allowing a view into deep time – in the Taos block of the Sangre, the rocks on the tops of the high peaks are among the oldest in New Mexico, having been created some 1.7 billion years ago. These rocks were formed along the collision zones between two ancient oceanic plates. The subduction of one plate beneath the other resulted in volcanism and the construction of “island arcs” – this volcanism melted the oceanic crust and slowly separated out lighter elements and rock types and built fragments of continental crust (the crust now sits beneath all of New Mexico). The rocks of the Taos block are complex as would be expected for an island arc environment. There are metasedimentary, metavolcanic and granitic rocks along with some diabase dikes exposed within 20 miles of the Taos Ski Valley. Although the 1.7 billion year old rocks are exposed elsewhere in a few places in northern New Mexico, a small outcrop on Lake Fork Peak holds the record for oldest dated sample in the state – 1.765 billion years. You have to climb high to see the birth marks of our state.

Geologic cross-section through the Sangre de Cristo mountains near Taos. The Sangre are a large horst uplifted along the Sangre de Cristo Fault system; the rocks of Wheeler Peak have been uplifted at least 10,000 feet.

After the formation of the ancient New Mexican crust in the Proterozoic times plate tectonics cast a dynamic history for northern New Mexico. Unfortunately, that history has been mostly erased from the high Taos mountains. Uplift and erosion have removed the veneer of sedimentary rocks that recorded the growth and breakup of ancient continents like Pangea. Today, the geology map of the Wheeler Peak Wilderness area is, well, sort of boring.

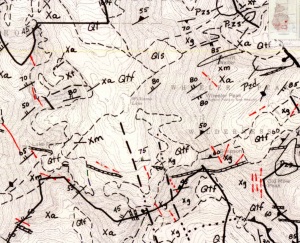

Geologic map of the Wheeler Peak Wilderness area. In faint lettering Wheeler Peak can be located in the center of the map, along with Williams Lake which is dead center in the figure. The symbols are indicators of rock type: X means proterzoic, with m,a, and g being a rock type. Q means recent – these are all talus slopes! No sedimentary rocks, almost no dirt.

But that relatively simple map belies the most recent geologic epochs that carved the present landscape. As the Sangre de Cristo began to rise with the opening the Rio Grande rift erosion also began – but overall, uplift won the competition. However, simple “erosion” does not explain the rugged topography. The agent most responsible for today’s vista is ice. During the Pleistocene Epoch (the last 1.8 million years) the Sangre have experience numerous episodes of cool, wet climate which saw glaciers develop and carve the mountains. The Pleistocene is a bit of a odd epoch because it is defined by the growth and decay of continental ice sheets (ah, climate change! but climate change driven by Milankovitch cycles. By the way, I would be remise if I did not mention that the Pleistocene was named by the great Scottish geologist Sir Charles Lyell); the last of these ended about 11,000 years ago. When one drives up to the Taos Ski resort you travel through the Valley of Rio Hondo, which was carved by a glacier that flowed from Wheeler Peak to nearly the Rio Grande.

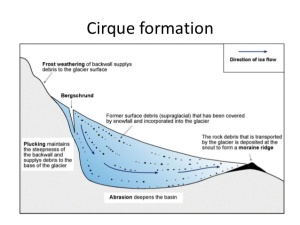

A cross section through an alpine glacier carving a cirque. The glacier is fed up slope with new snowfall. The seasonal snowfall also brings boulders and detritus into the glacier which acts as an abrasion agent to carve a basin as the ice flows.

The head of this glacier is the bowl shaped valley that is framed by the Alpine Loop. This is a classic glacial cirque – in the UK it would be called a Corrie after the Scottish Gaelic word corie, meaning a pot. In the Sangre, cirques are formed on the north side of high peaks – protected from the melting heat of the sun – near what is known as the “firn line”. The alpine glacier is surrounded by 3 high walled cliffs; as the climate becomes warmer the glacier tail melts in the valley below the cirque, ultimately leaving behind a lake which forms above a dam of detritus – the glacial moraine. Williams Lake is all the remains of the great Wheeler glacier today, but steep topography took tens of thousands of years for the ice to carve.

The ice has passed, but the youngest feature in the Williams Lake cirque is a glacier of a different sort – a rock glacier. Below Lake Fork Peak there is a debris flow; it looks like a viscous landslide. This is a rock glacier that was probably active until the last century. Rock glaciers are talus fields that have fallen off the sides of a cirque onto the retreating and shrinking ice glacier. Eventually, the rock blanket has only a small amount of ice within its core – but enough ice such that the rock blanket episodically “flows”, or more correctly, “creeps”. The rock glacier in Williams Lake cirque does not have a name (at least that I know of), but is a geologic reminder of the changing climate.

Rock glacier flowing from Lake Fork Peak towards Williams Lake (take early in the morning, 7/16/16).

The juxtaposition of the New Mexico’s oldest rocks with one of its youngest geologic structures is compelling theater for an Earth scientist. The run of the Alpine loop affords fantastic views; it also tells a story of the tremendous forces shaping our world.

A view from Wheeler Peak across the Williams Lake Cirque to Lake Peak. The Alpine Loop follows the ridge line all the way around the cirque.

Running the Ridge Line

Growing old(er) is a two edged sword. The positive slice is experience and the wisdom that experience brings. The negative slice is a decline in physical abilities, and at least in my case, memories of things unpleasant or hard fades far faster than those memories of excitement and joy. Some 42 or 43 years ago I hiked the Alpine Loop with teen aged friends; memory serves that it was an exciting backcountry adventure, and although I recall some scrambling over steep and rocky outcrops, I don’t recall it being difficult in anyway. So my expectations on starting the hike/run at about 6:30 am on a warm Saturday morning (it was 47 degrees at the Williams Lake Trailhead, which is at 10,000′ elevation) was that I would cruise along the ridgeline above Williams Lake in a couple of hours, and “run” significant sections of terrain above timberline.

The GPS track for the Alpine Loop. Starting at the Williams Lake trailhead I went nearly straight up the steep valley that the Kachina Ski Lift now serves, and follow the ridgeline of the Williams Lake Cirque in counter-clockwise fashion. Once the ridge line merges into the high country of the eastern border the course becomes class one trail.

Kachina Peak is near the boundary between the Taos Ski Valley and the Wheeler Peak Wilderness. The ski lift to the summit of Kachina was only built and opened in 2015 (and by all reviews, provides a spectacular ski venue). The summit is about a 2000′ climb in elevation from the trail head over about 1.7 miles.

The view of the climb up Kachina shortly after leaving the Williams Lake Trail Head. The chairlift at the summit is visible in the center of the photo.

There are some service roads supporting the chair lift for about half the accent. However, I chose to go “full wilderness” and trekked straight up slope. In places it is quite steep – my nose was only a foot away from the ground slope on some sections of the climb. The climb is strenuous, but not really difficult. The reward at the top is a monument of Tibetan prayer flags. Although beaten and shredded by the strong winds, the monument pays homage to the belief that prayers blown by the wind will spread the good will and compassion on to the surrounding land.

The summit of Kachina Peak. Not one of New Mexico’s high peaks, but the beginning of the Williams Lake cirque ridgeline.

The summit of Kachina affords a view of the entire ridge line above Williams Lake. At 7:40 in the morning the sky is a beautiful blue, and surprisingly, there is no wind. Only the high pitched chirp of a pair of marmots disturbs the scene.

A view of the journey ahead. My goal is to stay as close to the ridge line as possible. The high peak on the right is Lake Fork; in the middle of the photo is Sin Nombre. From this point until the descent off Wheelers the elevation never drops below 12,200′

The pathway to Lake Fork peak is not difficult. Within a few hundred yards of Kachina there is no discernible trail to follow, but then it is possible to run — although at a slow pace — until a scramble over a boulder field on the shoulder of Lake Fork. Along the scramble I pass three different collapsed mine shafts; all small, but nevertheless testament to the hardy breed of prospectors that covered this area in search of gold. In 1869 placer gold was found near the present site of Red River, about 10 miles north of Williams Lake. Although not much mining was done for 25 years, but the beginning of the 20th century the Taos block of the Sangre de Cristo was swarming with prospectors. The mineral potential of the Precambrian rocks of Lake Fork is actually quite small – but it did not stop fortune hunters from exploring even the most inhospitable crags and crannies.

A small collapsed prospect on the shoulder of Lake Fork. I believe that the prospector was following the vein of white quartz scene in the left part of the photo. The rising sun makes for “interesting” photography!

I had predicted how long it would take me to run/hike the various parts of the Alpine Loop (one could argue that there was zero basis for these predictions, but that has never stopped me in the past). I summited Lake Fork about 20 minutes behind schedule, and I was feeling that overall the route was actually easy.

The view from Lake Fork north, back to Kachina. The dome above timberline in the near skyline is Gold Peak.

However, the ill-founded optimism was soon tested. Lake Fork peak is a smooth summit, and once again it is possible to run along the crest. However, the descent down, and then up, to Sin Nombre is the first real taste of route finding. It is not overly difficult, but the progress is cautious and slow.

Sin Nombre looking back to Lake Fork Peak. The route is along the crest that twists from left back to the center of the photograph.

The views in every direction from Sin Nombre are spectacular. There is almost no wind, and the sun is bright – the temperature is rising, but still manageable.

A small, unnamed lake southwest of Sin Nombre. In the distance is the Truchas Peaks, where most of the other highest points in New Mexico reside.

After a nice food break I am ready for what I know will be the most difficult part of the Alpine Loop – the scramble down Sin Nombre followed by the rough climb up to Simpson Peak. My childhood memories of this scramble are fuzzy – somehow I did not recall that the route ahead – maybe 1.2 miles – was a solid class 4 (the rating scheme states: “Climbing. Rope is often used on Class 4 routes because falls can be fatal. The terrain is often steep and dangerous. Some routes can be done without rope because the terrain is stable”).

The route to Simpson Peak (Old Mike is a 13er on the right hand skyline). This route alternates between very loose rock (I did take a nasty fall) and climbing. In hindsight it was fun….

It took me over 2 hours to cover the this traverse. At sixty, and with artificial joints, I forget how inflexible I really am. My knees barely bend; my hips even less. Climbs that younger hikers could scramble up required the power of prayer for me. I never really thought I could not make it, but it was tough. However, my slow pace allowed me to experience the full adventure. As I tumbled down a cornice I spied a spectacular boulder of metagreywacke!

This boulder represents the sands and clays that were eroded off the volcanoes forming the continental crust 1.7 billion years ago. This volcanic detritus was eventually buried and metamorphosed into the banded rock I see in rock before me.

Looking back at Sin Nombre from the low point between that peak and Simpson Peak. I left some blood on those rocks!

After the long climb back up to Simpson Peak (the peak is named for Smith H. Simpson, who moved to Taos in 1859 and served with Kit Carson), all the tough sections of the Alpine Loop were completed. Although Simpson Peak is not far from Wheeler peak, it is usually abandoned. Everyone wants to hike the high point in New Mexico, but ignore all the wonderful summits near by.

The summit of Old Mike looking toward the east; Eagle Nest is visible in the center of the frame. Old Mike is the third highest peak in New Mexico

From the summit of Simpson Peak it is only a short jog to Old Mike. Old Mike is the southern most of the high peaks in the Taos block of the Sangre de Cristo. I love the views from Old Mike – you can see the Truchas in the south, Eagle Nest lake in the east, and the community of Red River to the north. It is only a mile from Wheeler Peak, but I have the summit and trail back to Wheeler to myself. Wheeler peak looks like an ant hill from Old Mike with people swarming the top (what a difference that mile makes!). On the journey over to Wheeler I meet up with a good friend, Dale Anderson. He is my “pacer” for the journey back to the Williams Lake trailhead.

Dale Anderson and I at the summit of Wheeler Peak. Windy and always, we see about 50 people on the peak or in various stages of ascent and descent.

Wheeler Peak is a wonderful place – crowded, but still wonderful. Wheeler Peak is named for George Wheeler who lead one of the great expeditions to map the western US in the 1860s and 70s. Wheeler was only 27 when he was commissioned to lead an expedition to New Mexico and Arizona in 1869 – he was awestruck with what he found, and in 1871 convinced congress (a difficult feat even in the 19th century!) to fund mapping of the United States west of the 100th meridian on a scale of 8 miles to the inch. Coarse resolution to be sure, but it was one of the most ambitious projects ever undertaken for the country.

The view from Wheeler to the west, back over the Alpine Loop. The green marks the tree line in the Williams Lake cirque.

From Wheeler Peak it is a quick jog over to the second highest peak in New Mexico, Mount Walter. Walter is along the Bull of the Woods trail to Wheeler, so it is fairly well traveled. However, today no one is on the peak, and the journey of the Taos high country is complete.

The trail from Walter back to the Williams Lake Trailhead is about 3 miles, and drops nearly 3000′. Some of it is runable, some of it is not when you are tired – but it is all easy.

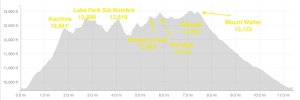

Elevation profile for the Alpine Loop (from my GPS track). There is some doubling back, but the profile is 8 miles well above 12,300′ What is missing is the class four scramble….

One last geologic landmark to pass on the Alpine loop is the glacial toe moraine for Williams Lake. It does not look like much, but it is the last reminder of an ice age past.

Williams Lake is just beyond the ridge in the center of the photograph. The rubble is the moraine that dams the drainage from the high peaks – in turn creating Williams Lake.

Short Memories for Bad Things

The Alpine Loop is a wonderful wilderness experience. For much of the trek you are truly alone, and the geology is spectacular. Sometimes when I plan an adventure I like to frame it in terms of a “run” or “run/hike’ – but those are just tags that really have little meaning to experiencing the wilderness. It is as congress wrote 52 years ago a place of “other” not of man. By the way, any memories of the difficult times I had scrambling over loose rock and wondering if this “whole thing was a good idea” are already beginning to fade – what is left is the glow of joy.