“Joy to you, we’ve won”, the final words uttered by Philippides upon running from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory over the Persians, circa 490 BC. Philippides was a professional day-long runner delivering urgent messages. He is an inspiration for ultra runners — he ran first to Sparta to plea for help (240 km over two days), and then ran the 40 km from Marathon to Athens before expiring.

Top of Handies Peak, San Juan Mountains, early June, 2009. The view is to the southeast, and you can see above timberline for 35 miles.

Calderas, collapse, karats, and cannibals, oh my! The tiny town of Lake City in southwestern Colorado is the home to a magnificent mountain ultra, the San Juan Solstice 50 miler (SJS50). Lake City is the epicenter of unbelievably beautiful high mountains, amazing geology, mineral and mining history, and only a few miles from the most infamous episode of cannibalism in the old wild west. In my opinion the San Juan Mountains are the most beautiful in the world, and the mining history has drawn me to the range for 50 years; the opportunity to run a long race through the mountains I have known was something incredibly special that I just had to do (even if I was only marginally qualified for the extreme course!).

Michelle Hall, my wife, on her first 14er Handies Peak. Over her shoulder Uncompahgre and Wetterhorn (more 14ers) are visible. Handies is a couple of miles southwest of the SJS50 course.

I first visited the San Juans with my father on a mineral collecting expedition in the early 1960s. Although I have no real memory of that adventure, I know that it was the first of more than 50 trips we would take before I left home for college. I visited every mining camp, large and small, across the San Juans looking for mineral treasure. I found silver, gold, rhodochrosite, great quartz crystals, galena, hubnerite, and artifacts galore. But mostly, I found a place that inspired and thrilled me, and connected with my soul. The San Juans are no longer a “hidden gem”; they are visited by more than 150,000 people every year. Telluride has become a major ski resort and playground of the rich. There are dozens of companies that provide jeep tours to some of the most remote and rugged corners of the range, and sometimes in the summer there are more than 500 ATVs ferrying people to vistas they could barely imagine before they got to the San Juans. However, despite its growing popularity, the San Juans are still a wilderness, and there are ample opportunities for solitude and reflection — along with climbing, camping, running, and yes, even mineral collecting.

Collecting minerals. My grandson’s first mineral collecting trip was to TomBoy located in the San Juans above Telluride. He was 2 and half years old, and found lots of rocks…and a taste of the world’s most beautiful mountain range.

The San Juans are where I took my then-to-become wife on our first “very serious” date. Once she camped above timberline, and pounded on rocks looking for silver, and had to purify water before breakfast, we knew that we were right for each other. She saw Cement Creek, Cinnamon and Stoney Pass and the ghost town of Animas Forks before she met my parents. Years later we returned for a celebration of an anniversary and she climbed her first 14er, Handies Peak. Later my son would also climb his first 14er there, and it transformed him into a “mountain man”.

Lake City is on the north-central flank of the San Juans, and is less well known than the “big three” mining towns that brought much fame to the area: Silverton, Ouray, and Telluride. However, Lake City is just as historic, and is only a few miles – as the crow flies – from 5 peaks that top 14,000 feet. The San Juan Solstice 50 started as the Lake City 50 miler back in 1995. The terrain is spectacular, but also poses challenges for snow pack and summer lightning storms – much of the course is above timberline. In the early part of last decade the race assumed its modern name, and the goal of running close to the solstice became a mantra. The SJS50 is extremely popular, and requires runners to qualify and signup for a lottery for the 250 available spots. The lottery and wait list adds drama to the hopeful runners, but the real challenge is waiting to see if the snow pack cooperates with the third week in June. In 2015 it was touch and go – an amazing wet late spring kept the high country under a thick white blanket. Snows finally began to melt in mid-June – and boy did they melt, sending roaring runoff down the drainages. This set the stage for a true adventure – a 50 mile run with more than 12,800 feet elevation gain and loss, a low point of about 8,700 ft elevation, and an average elevation of approximately 11,000 ft, snow fields, and 9 stream crossing with churning melt waters. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, it turns out lots can go wrong – flat tires on 4WD roads, warning for missing 25 mile/hour speed limits, and most unfortunately, a bad trip on a downhill run that ends a race early. However, the SJS50 is now a life challenge for me.

Artifacts from the Ute and Ulay mines, located just beyond Alpine Gulch. In the early part of the 20th Century there was a major struggle between newly formed unions and mine management that played out across the mining camps of the Southwest. Pictured are two union ribbons and a ceremonial “sliver slug” stamped “Ulay” (the slug is about 2 inches across). These artifacts are from the collection of a close friend, Dave Bunk. The history of the Lake City is really about the miners and mines – and what is left today are these wonderful artifacts. Jesse LaPlante photograph.

There’s gold in them thar hills (with a shout out to Mark Twain)

I have written several articles on the San Juans – some for technical journals, and some for more popular literature. Recently, Gloria Staebler and Lithographie published a monogram, The San Juan Triangle of Colorado; Mountains of Minerals that captures the spirit of the geology and the wonderful minerals. From my writing in the monogram I attempt to tell the tale of the 8th wonder of the world.

Lithographie monographie on the San Juans (http://www.lithographie.org/bookshop/the_san_juan_triangle.htm)

The San Juan Mountains are a spectacular range of towering and rugged peaks that cover an area larger than the entire state of Vermont – 25,000 sq km of alpine bliss in southwestern Colorado. The range stretches from Creede in the northeast to Durango in the southwest; the San Juans are home to 14 peaks over 14,000 feet in elevation and hundreds of peaks that top 12,000 feet. The topography is extraordinarily steep, and much of the range is above timberline. The imposing landscape was shaped by some of the most violent volcanic eruptions known in geologic history. Between 35 and 26 million years ago huge volcanic centers rose and collapsed and erupted 10s of thousands of cubic km of rhyolitic and andesitic tuffs. The scared landscape that remained was full of factures and faults that would later localize the magmatic fluids that deposited the ore bodies of some of Colorado’s richest mining districts: Creede, Summitville, Silverton, Ouray, Telluride, Rico, and of course, Lake City.

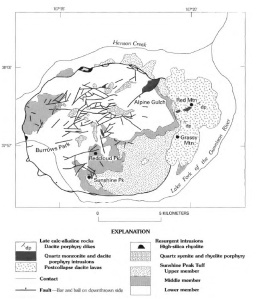

The volcanic centers of the San Juans. The western-most center is a series of calderas that formed over a 5 million year period nearly 28 million years ago. The initials “LC” denotes the Lake City Caldera, home of the SJS50.

The extraordinary episode of volcanism that created the San Juan Mountains began at the end of the Eocene (a geologic epoch 56-34 million years ago). More than 30 centers of volcanism formed through out southern Colorado and northern New Mexico in what is known as the Mid-Tertiary Ignimbrite Flare-Up. These volcanoes probably looked like stratavolcanos that form above subduction zones (eg, Mount Rainier and Mount Fuji) but they produced far more voluminous eruptions. Initially, the eruptions produced andesites and explosive ash falls, but starting about 30 million years ago huge sheets of pyroclastic flows were erupted. The pyroclastic flows are welded tuffs known as ignimbrites. These flows are unparalleled in size; within the San Juans there are at least 22 flows that are larger than 100 cubic kilometers. The only way to explain these flows is to assume nearly continuous eruptions for dozens of years. The eruptive centers ultimately collapse forming large calderas. The largest eruption known in the geologic record occurred in the San Juan Mountains at the La Garita Caldera north of Creede (denoted as LG in the figure above). La Garita produced the Fish Canyon eruption 28 million years ago; the Fish Canyon Tuff was voluminous – more than 5000 cubic kilometers! The Fish Canyon tuff could fill Lake Michigan! Equally remarkable, after La Garita erupted the Fish Canyon tuff, the volcanic system continued to be active for 1.5 million years producing at least 7 other major eruptions.

The reason for the Mid-Tertiary Ignimbrite Flare-Up is a subject of geologic debate, but most geologists believe that the volcanism is related to the tectonics along the west coast of North America. The Laramide Orogeny, which resulted in the uplift of much of the Rocky Mountains along an arc from Canada to New Mexico, is thought to be related to the subduction of the Farallon oceanic plate beneath North America. The Farallon plate was quite young geologically, and thus buoyant. This likely resulted in a shallow angle of subduction, which caused an uplift of the entire western US. About 35 million years ago the last bit of the Farallon plate was subducted resulting in a major re-ordering of plate tectonics on the western edge of the North America. Without subduction, the Farallon plate began to simply sink through the mantle in a process that is known as “slab roll-back”. This allowed very hot mantle to melt large regions of the lower most crust, and created the magma sources for the ignimbrites. The eruptions of ignimbrites lead to the collapse of the huge calderas throughout the San Juans and developed a structural fabric that would localize much younger volcanic activity, which would give rise to rich mineral districts.

The Lake City Caldera (from Bove et al., 2001). The high peaks between Henson Creek, which passes through Lake City, and the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River are all volcanic centers that erupted about 22.5 million years before the present. Collapse of the volcanic center produced an elliptical depression – about 1/2 the diameter of the Valles Grande Caldera near Los Alamos.

In the area defined by the San Juan Triangle (Telluride-Ouray-Silverton, and over to Lake City) there are four collapsed calderas; the Uncompahgre, San Juan, Silverton, and Lake City. The first three were formed during a time period of 29 to 27 million years ago. The Lake City caldera was the last to form, at the end of the ignimbrite flare up, 22.5 million years ago. The geologic record within the San Juan Triangle is complex and difficult to interpret due to the superposition of the calderas and their structural manifestations. The Uncompahgre and San Juan calderas are the oldest; they were active at the same time, and collapsed simultaneously with the eruption of a very large ignimbrite sheet. The ring faults associated with the Uncompahgre and San Juan calderas form an oblong structure that is about 45 km by 15 km, trending southwest-northeast. The formation of the Lake City Caldera was the last gasp of the Mid-Tertiary Ignimbrite flare up. The rich ore deposits in the San Juan Triangle were emplaced 5 to 15 m.y. after the calderas formed. This mineralization is classified as epithermal and is associated with minor episodes of magmatic activity. The base metal deposits contain mainly galena, sphalerite, and chalcopyrite while the precious metal deposits are mainly native gold. Silver occurs in a suite of exotic minerals that includes tetrahedrite/tennantite, proustite, and pyrargyrite. Gangue minerals include quartz (most common), calcite, pyrite, pyroxmangite, rhodochrosite, fluorite, and barite.

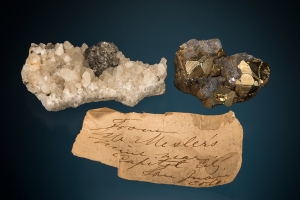

Minerals from “Mr. Mesler’s Mine”, which was located in Capitol City, and short distance beyond Alpine Gulch on Henson Creek (about 9 miles from Lake City). From Dave Bunk’s collection (Jesse LaPlante photograph).

There were hints of the great mineral wealth of the San Juans in the earliest expeditions exploring the western US. In 1848, John Fremont led a privately funded expedition into Colorado to scout a route for an intra-continental rail route along the 38th Parallel. The expedition was a disaster due to an exceptionally cold winter, but an unnamed member of Freemont’s party discovered gold nuggets and flakes near present day Lake City. The exact location of the discovery is not known, but it was probably the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River, and may well have been related to the future Golden Fleece mine, which would become Lake City’s most famous mine 30 years later. This is the first documented discovery of gold in the state of Colorado, although it was largely ignored.

In 1859 gold was discovered along the Front Range, west of present day Denver. This coincided with the decline of gold mining along the Sierra Nevada of California and created a rush of prospectors to Colorado. This became known as the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, although the gold discoveries had nothing to do with the famous 14er. The huge influx of prospectors far outstripped the easily won gold in the Denver area, and prospectors fanned out to other parts of the Rockies. In the late summer of 1860 Charles Baker led a party of gold seekers to the San Juans. Baker entered the San Juans along the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River – he walked along part of the course of the SJS50! His party eventually passed over Cinnamon Pass, and discovered gold along the Animas River near Silverton. There was no putting the genie back in the bottle – mining became the heart beat of the San Juans for a century. The early years were extremely difficult; the San Juans were actually part of land the US government had agreed was owned by the Ute Indians, the area was so remote that it was nearly impossible to supply and provision, and the mining season was short and harsh due to the alpine environment. In 1873 the Brunot Agreement opened the land to mining (the Utes in return received $25,000 annually in royalty, and the right to hunt), and soon toll roads and narrow gage trains began to “civilize” the area.

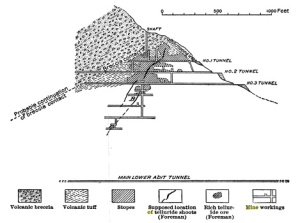

Early cross-section of the Golden Fleece Mine.The upper reaches of the mine assayed at 125 oz of gold and 1250 oz of silver per ton.

The first major mineral discovery near Lake City occurred on August 27, 1871 Henry Henson discovered a rich silver deposit – to be called the Ute-Ulay – along a stream about 3.5 miles from the present location of Lake City. Later this stream would be named Henson Creek (the SJS50 follows Henson Creek for the first 2.5 miles of the course). Once the Brunot Agreement was signed, Henson returned and developed the Ute-Ulay mine, which was a major silver and lead producer (but few mineral specimens exist today – a pity). This development attracted entrepreneurs of every type; one of these was Enos Hotchkiss who came to build a toll road but instead discovered gold above Lake San Cristobal, a couple of mines south of Lake City. Hotchkiss did not find much gold at first – in fact his claim was largely based on the obvious color of the rock – anyone with a sprinkling of geologic knowledge just has to gaze up Red Mountain and see the beautiful color of an oxidized cap, and know that there is gold in them thar hills. However, the claim was enough to commit to prospecting, and Lake City was founded on this promise. Eventually the Hotchkiss claim was renamed the Golden Fleece Mine, and became one of Colorado’s most famous. The early years of the Golden Fleece relied on telluride ores, and there are reports of individual mining carts assaying 50,000 dollars of bullion. I have been underground at various adits associated with the Golden Fleece looking for rumored veins of hessite, one of my favorite minerals. Alas, like most old San Juan mines, the conditions are deplorable, and one is actually just lucky to get out alive.

Stock certificate from the Golden Fleece mining and milling company dated 1896. Although the Golden Fleece produced silver, and thus was impacted by the 1893 silver crash, the steady production of gold helped the property make it through the “silver crisis”. Dave Bunk collection.

The news of the Golden Fleece started a “Lake City” rush. By 1880 there were dozens of mines in Carson (along the SJS50 course), Argentum and Capitol City. The population of Lake City swelled to 2500, and the boom times were full steam. However, silver soon ran into the buzz saw of politics. The rich deposits of the San Juans began to push the price for silver bullion down, and western mining barons demanded action. In 1890 Congress passed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which required the US government to purchase $4.5 million dollars worth of silver every month. This proved to be as unpopular among the Republicans of the day as the Affordable Health Care act today, and was repelled in 1893 – and the price of silver plummeted. In a few week period the price dropped from $1.50 per oz to 63 cents. At the time, Colorado produced about 2/3 of all the silver in the country; within 2 years more than 1/2 the silver mines in Colorado – including those near Lake City – were shuttered. Although the mining industry would eventually recover, the heyday had passed. Today there is some mining in the Lake City area – for example the Golden Wonder Mine located at the head of Deadman’s Gulch – but mostly there is history of an incredible tough breed of pioneer that has long passed.

Rhodochrosite, Champion Mine, Dave Bunk collection. The Champion Mine is located near Cinnamon Pass – the road over Cinnamon Pass was built by Enos Hotchkiss. Jesse LaPlante photograph.

In 1911 Irving et. al published Geology and Ore Deposits near Lake City, Colorado. In the text is a haunting statement: “Secondary enrichment…led to the formation of the rich bonanzas of ruby silver found here and throughout …” Oh, to find a pyrargyrite or proustite from Lake City! I have not in 50 years, so I suppose I am happy to run the San Juan Solstice instead.

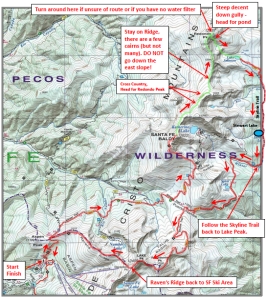

Google Earth Image of various points along the SJS50. The course starts in Lake City and head west on Henson Creek, then south up, way up, Alpine Gulch. The course turns towards Redcloud Peak, a 14er, but before arriving there descends into the Lake Fork valley. After crossing the valley the course climbs steeply up to the continental divide, and has 15 miles above timberline.

50 Miles, a clock ticking, and then a trip

Lake City is a small town, and every resident seems to be involved in the race. The Lake City of my youth was a decaying frontier mining town; like nearly all Colorado mountain mining communities it has been gentrified and is now a destination for outdoor enthusiasts of all sorts. Gentrification came decades later than to Aspen or Telluride, so it is still has the rustic flavor of the early part of the 20th Century. But make no mistake, expensive vacation homes and a very fine French Chef are now part of the Lake City landscape. The SJS50 checkin is most of the day before the race – lots of hard core trail runners from all around are wandering the small town park that serves as the start and finish to the race. It does not take insightful self awareness to immediately recognize that I am not really “like” most of the runners. However, that is not why I run, and I am truly excited to be in the San Juans.

The final checkin for race begins at 4 am on Saturday, June 27. I put my drop bags into the piles for a couple of the aid stations, and begin to get nervous. Visiting various parts of the course the day before I know that it will be wet and muddy, so I have a couple of extra pairs of shoes, lots of socks, and of course, my special energy supplies tucked into my drop bags that proudly displace my name and bib number. In ultras your bib number is aways assigned alphabetically, so my bag is pretty easy to find (although not as easy to find as my friend Dave Zerkle from Los Alamos….). At 4:55 a soft bull horn announces that the race will start in 5 minutes. I hustle into position, but it seems strange to me that runners are still milling around the park or standing in line at the port-a-potties. Suddenly I hear, with no warning, a growled “GO”, and people are off running. There are also runners running from the port-a-potties. I realize that 13 or 14 hours running will not rely on a punctual start.

The glint of reflective tape and headlamps at 5 am start of the San Juan Solstice. A bit of a chaotic beginning, but a perfect morning.

The first 2.6 miles of the race are up a gravel road along Henson Creek. There is not much chit-chat, and the sounds I hear are the crunch of 500 feet on the road gravel and mixed with the turbulent roar of Henson Creek bringing snow melt down from the high country. Dave Zerkle and I settle into a very agreeable pace of a little better than 11 minutes per mile (the specter of 50 miles looms large). When we arrive at Alpine Gulch we start the real race. Although we have climbed 500 feet thus far, in the next 6.5 miles we have nearly 4000 feet elevation gain. The sun is still an hour from lighting the narrow canyon, but there is enough glow to switch off the headlamps. The creek in Alpine Gulch is churning, but the water is much lower than just a week before. At mile 3.75 we come to the first of 7 (or 8, 9, or 10, but who is counting) crossings of the creek. The crossing has a rope for assistance, and a number of volunteers to offer advice. The runners stack up waiting for their chance to jump into the frigid waters…the first step is a doozy, although the water is only a bit above my knees. Cold, but I am surprised how good it feels!

The first river crossing along Alpine Gulch. This photo was taken the day before the race, scouting the various segments. The picture does not give a great sense of the water depth, but it is about 2.5 feet here. At some of the higher crossing the water is definitely crotch level.

The course criss crosses the gulch many times, and at each water entry there are volunteers and a rope. Some crossing are more challenging than others, but every time the runners emerge with soaked shoes, socks and compression sleeves. I really enjoy the crossings, except they continually bunch the runners. Dave Zerkle and I are trying to maintain a 20 minutes per mile or better (the average grade on most of the climb is 17%). For the most part, the running dynamics are such that we can pass the slower runners, and get passed by the occasional faster runner (probably the people that were in the port-a-pottie when the race started). However, around mile 6 I become quite impatient with the “group-pace” and ask to semi-sprint past a dozen runners. It is hard work, but rewarded with open trail. A downside is that I lost Zerkle. The first aid station is located at a small saddle at mile 7.6. The cutoff time for this station is 7:45 am – in other words, 2hr45min from the start. Sounds easy, but the climb is tough. I planned on arriving at 7 am, and I am 6 minutes early. I feel fantastic, and have visions of a sub-13 hr race.

View of the south side of Red Mountain from Aid Station #1. The red color that is usually so distinctive is muted in the early morning sun. However, on the ascent up the gulch there are many old mines and the cabins of prospectors past.

Although the aid station is at a saddle, the climbing continues. I am still moving well, not really tired, and hypnotized by the scenery. I feel like I am home. Shortly before summitting at the high point of the first part of the course I catch up to another runner from Los Alamos, Sarah Thien. She has been battling an injury, and is not her usual rapid self. We do get to chat a bit, and both marvel that the mountains surrounding us.

The first climb is nearly over – a pass on the shoulder of an unnamed 13,600 foot peak visible over my left shoulder. The day is spectacular! In the distance I can see Handies and Sunshine Peaks.

Once on the divide I know that the course is going to descend nearly 3500 feet in the next six miles. All those hard earned feet and inches of elevation gained are soon to be lost, and gravity wins again. I always have a difficult time shifting gears from climbing to running downhill. I suppose it is the stiffness of age, but my hips always have to be convinced that it is okay to have strides longer than 10 inches. After a mile or so I am beginning to hit a stride of 11:30 minutes per mile; I had hope for 10 minutes per mile, but I am ahead of schedule never the less!

Sarah Thien running across the divide. The view is towards the west, and the high peaks of Uncompahgre and Wetterhorn can be seen in the distance.

There are a number of snow crossing, but the elite runners have post holed a pathway. The snow is soft and wet — and slippery – but mostly enjoyable. At mile 10.5 the snow is behind me, and the steep descent begins. I am excited and begin to try and sprint. Disaster strikes at mile 11 – I trip. I am on a steep trail section and tumble head-long downhill. I land hard on my artificial knee and my right forearm. The trail is rutted, and I am facedown, feet above my head, unable to get up. I realize this is bad, but I hope that it is a typical trail run trip where the blood is always worse than the damage. My dignity is challenged as I try and right myself – a woman runs past as I am still down and asks “did you fall?” Oh, if only I could have actually answered that question with a response it deserved!

I get up, and start downhill knowing that the Williams Aid Station is only 4.5 miles ahead. I can’t really run, but I am moving. Lots of runners now pass me, reminding me that hubris is a nasty sin. I am worried about my knee – being an artificial joint I imagine some horrific breakage. Hardly likely, but a concern nevertheless. My right foot (below my artificial knee) is totally numb. Every step feels like I am swinging a club attached to my knee. Before the fall I was on pace to arrive at the Williams Aid Station at 9:05 am. Instead I arrive at 9:32. I check in, and then very reluctantly, drop the race.

After clean up – once the blood and grim is removed, it does not look so bad. Well, at least the knee. Unfortunately, the day is done.

The medical staff help clean up the wounds, and I get bandaged up. My wife is at the aid station, and provides the sad sag-wagon ride back to Lake City. After only finishing 16 miles I am quite depressed. I look up on the ride in and see two parts of the course I very much looked forward to: Slumgullion and Vickers.

Michelle standing at the Slumgullion pass point of interest. Over her head is the scarp of the repeated Earthflows.

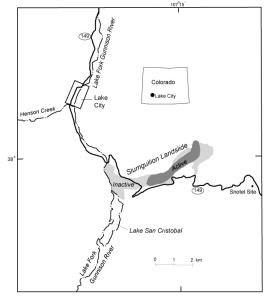

The Slumgullion Earthflow is one of the most interesting and odd geologic features on the entire run. In the 1870s this strange tongue of yellow chalky debris was identified as a landslide off Mesa Seco (the map below shows the geography of the slide). It was later recognized that the Slumgullion was not “a landslide” but a series of large scale debris flows that have been active for hundreds of years. About 1200 years ago the competent rocks on the top of Mesa Seco began to slide down towards the river valley because the underlying rocks, which are heavily altered ignimbrites from the Lake City Caldera complex, were exposed and rapidly eroded. The first flow damned the river and formed a prototype Lake San Cristobal. Eventually the river cut through this old debris flow and drained the lake, only to see two other episodes of mass wasting, one 700 years ago, and most recently, 300 years ago (and this flow is still active). The distance from the head of the flow – the scarp on the cliffs of Mesa Seco – to the toe is about 7 km, and 170 million cubic meters of material are contained within the scarp.

The Slumgullon – a large landslide due to the collapse of steep cliffs of decomposing volcanic tuff.

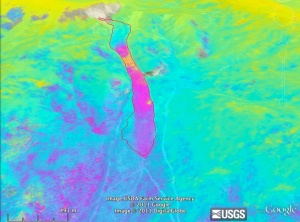

There is a section of the slide that remains active. At one time it was a standard geology student training exercise to measure downward movement with seasonal surveys. Today the movement is measured with SAR (synthetic aperture radar). The image below is from a pair of NASA overflights, and is colored to show the motion over a one week period in 2011. The red/purple colors show the most rapid motion, about 4 inches per week.

SAR image of the Slumgullion Earthflow. The slide is outlined in red, and the colors are constructed from the fringes of the differences between two radar images. The slide a few hundred meters above the SJS50 crossing is slowly moving downhill.

Although the Slumgullion slide is strange, it pales in weirdness to the last section of the course – the climb up Mesa Seco. The SJS50 course is very close to the Alferd (sometimes written Alfred) Packer cannibalism site – in fact we are probably running on the very ground that Packer’s victims camped on at back in 1874. Packer – with no real experience, but a gift for tall tales – guided 5 men to the area in February (the middle of winter!) to look for gold. It seems they were prospecting very close to the future Golden Wonder Mine (it is in Deadman Gulch, named for the Packer victims), but they became snow bound and quickly ran out of supplies. There are many versions of what happened next, but it is clear that Alferd killed and ate his companions to survive. For this reason I believe that the final aid station, named “Vicker’s” for the nearby ranch should actually be called Packer, and there should be bacon there…. I ponder what it must have been like to be in the San Juans 140 years ago. I often think I was born 100 years too late, and could have been a naturalist. Then I recall the amusing tale of the Hinsdale County Judge that presided over the trial of Packer and sentenced him to be hanged (the sentence was eventually overturned because Alferd ate his victims while Colorado was still a territory, and cannibalism was not a crime in the territory….really!); was reputed to have said: “Stand up yah voracious man-eatin’ sonofabitch…. When yah came to Hinsdale County, there was siven dimmycrats. But you, yah et five of ’em, goddam yah….Packer, you Republican cannibal, I would sintince ya ta hell but the statutes forbid it.” Ah politics, they have not changed in 140 years.

After I get cleaned up and rebandaged, I go to the finish line and wait for all my friends to finish. As the first runners come in I am struck how most look very different than runners after a 50K race. Here they are far more tired, looking thankful for the finish instead of happy. Nearly every runner I know tells a tale of how difficult the conditions were this year and how hard, very hard, the run was. I think of Philippides who’s legend inspires ultra runners — giving it all, raising their arms in victory as they cross the finish line, and crumpling to the ground in exhaustion. I suspect even Philippides would find the SJS50 challenging.

My morning after the race I have come to grips with my race-interupted. I have decided that this is something I can not leave undone. I will return in 2016 – in fact, it will be the focus of all my training for the next year. I also wonder how I can make the San Juans my home.