Both the man of science and the man of action live always at the edge of mystery, surrounded by it – J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was appointed the Director of Los Alamos Laboratory in November 1942.

View of a late spring storm over the Sangre de Cristo mountains viewed from Los Alamos (photo by Jim Stein, Los Alamos photographer extraordinaire, May 26, 2015). The peak in the center-left is Santa Fe Baldy (elevation 12,632 feet).

The town of Los Alamos sits high above the Rio Grande River on the Pajarito Plateau. The location of the town will always be associated with the Jemez Mountains and the spectacular Valles Caldera; however, the view from the town is always to the east, across the Rio Grande Rift, and towards the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The Sangre are the southern most range of mountains that are part of the Rockies, and the view from Los Alamos is dominated by a series of rugged high peaks – Truchas, Jicarita, Sante Fe Baldy Peaks all top 12,500′ – these rocky spires guard the Pecos Wilderness, one of the Jewels of unspoiled New Mexico.

The creation myth of the Los Alamos often casts J. Robert Oppenheimer as selecting the isolated and rugged Pajarito Plateau for the project Y laboratory because of a connection with the Los Alamos Ranch School, a boy’s college prep school. However, that is incorrect – indeed, Oppenheimer recommended and lobbied for a laboratory in New Mexico because of his affection for the area. But that attachment was with the area that would become the Pecos Wilderness Area. In 1922 Oppenheimer and his brother Frank visited the Pecos Valley and loved it – so much so, that the brothers first rented, and eventually bought, a ranch along the Pecos River which they named “Perro Caliente” (the legend is that when Oppenheimer found the land for sale he shouted “hot dog”, and the name seemed logical for the new ranch). When General Groves and Oppenheimer visited New Mexico to locate project Y the preferred site was near Jemez Springs. However, Oppenheimer convinced Groves that the high cliffs would make the scientists claustrophobic, and thus, unproductive. The next site visited was the Los Alamos Ranch School, and Oppenheimer beamed with joy at the view towards the Sangre de Cristo mountains, and exclaimed that the scientists would be inspired by the vast vista. Of course, to the is day, the scientists — at least this one — remain inspired by the magnificent mountains.

J. Robert Oppenheimer and E.O. Lawrence at the Oppenheimer Ranch along the Pecos River in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Oppenheimer often rode a horse from his ranch up to Lake Katherine just below Santa Fe Baldy.

The high mountain peaks of the Sangre are accessible by a number of trails that are only 35 miles from Los Alamos. These trails allow great entry into the high country for trail running (and hiking!); several of the trailheads are located at the Santa Fe Ski Basin, and are gateways to runs of 20, 30, and even 50+ miles at elevations that never drop below 10,000′. This is a perfect training ground for the ultras like the San Juan Solstice 50 Miler (June 27, only 2 weeks away) — so off went about 10 runners from Los Alamos and Santa Fe on June 13 to get some quality high altitude climbing and descending, and tasting the ever changing alpine weather.

The geologic story of Santa Fe Baldy

New Mexico is an arid state. In fact, it has the lowest water-to-land ratio of any of the 50 states in the US, and more than three quarters of the few lakes that exist are actually man made reservoirs. Despite this lack of water, or perhaps because it is so scarce, the human history of the state is dominated by a narrow ribbon of water that bisects New Mexico, the Rio Grande River. The Rio Grande is long, but not wide, and only in New Mexico would the name “Grande” be applied to this river. The stream gauge at Otowi Bridge — on the hiway route from Los Alamos to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains – read 2500 cubic ft per second the morning of June 13, 2015 (the Mississippi River flow was 220 times larger at St Louis this morning). However, this modest flow supports the state, and 75 percent of the state’s population lives within 50 miles of the Rio Grande.

The Rio Grande River is also a remarkable geologic marker. The headwaters are in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado, and entire course of the river through New Mexico follows a topographic depression that traces the Rio Grande Rift (RGR). The RGR is relatively uncommon geologic phenomena, a continental rift (there are only three others in world), and it represents a stable continental plate slowly being torn apart; or more correctly, stretched apart. The RGR stated about 25-30 million year before the present, and represents the end stages of extensive crustal extension throughout the southwest. The crust between the California-Nevada border and the Tucson, Arizona extended by as much as 50% during this time. The RGR is presently opening at less than 2 mm per year, but integrated over millions of years this has created a “hole” where the crust has been stretched apart. This hole is instantiated by a series of basins that have been filled with the sediments transported down the Rio Grande River.

The trace of the Rio Grande Rift is marked by a deep graben, which is mostly filled with sediments that have washed down the Rio Grande River over the last 25 million years. Los Alamos sits on the western margin of the Rift, and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains are along the eastern margin. Between Los Alamos and Sante Fe Baldy is the Espanola Basin.

The figure above shows the largest of these basins, including the location of the Espanola Basin which sits between Los Alamos and Santa Fe, and is more than 10,000 ft deep and filled with ancient river sediments. The flanks of rifts are almost always elevated relative to pre-opening of the rift. This may seem counter intuitive given that the opening of the rift creates a “hole”. However, the opening of the rift is usually associated with ascending hot mantle material, which “lifts” the region overall.

Conceptional cartoon for continental rift dynamics. Ascending hot mantle materials raise the elevation, and as the crust is extended a rift valley forms. The flanks of the rift are often uplifted high mountains with steep faces sloping into the rift valley.

This is the case for the entire eastern flank of the Rio Grande Rift in northern New Mexico. The present topography of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains owes its existence to the opening of the RGR. The Sangres are an ancient mountain range and certainly were part of a proto-Rocky Mountains. However, studies of erosional surfaces indicate that 35 million years ago the prominence of the Sangres was only a thousand feet. Opening of the rift allowed the rocks of the range to rise to their present elevation and develop and prominence of over 7,500′.

Geologic map of the Pecos Wilderness Area. The western margin is a block of plutonic granitic rocks that have been uplifted during the opening of the Rio Grande Rift. This block contains all the high peaks of the Sangre de Cristo range (from Robertson and Moench, 1979).

The core of the Sangre de Christo Mountains in the Pecos Wilderness area are Precambrian plutonic granites (and granitic gneiss). In the figure shown above, the large elongate block on the western side of the map shows the extent of this plutonic rocks which are approximately 1.6 billion years old. They are fragments of the original North American crust that were probably formed 5 to 10 km beneath the surface of the Earth.

The topography from the Jemez Mountains to the Sangre de Cristo Range are due to the dynamics of the Rio Grande Rift. In fact, the entire landscape of the New Mexico has been influenced and shaped by the RGR. As a geologic architect, the rift is Frank Lloyd Wright.

Looking up at Santa Fe Baldy from the Winsor Trail just beyond the Rio Nambe crossing. 2000 feet to climb in about 2.5 miles. Steep and sweet.

Sky running in the Sangre

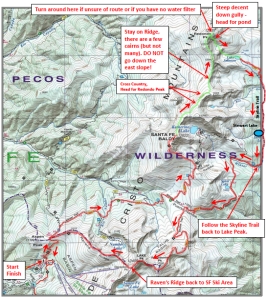

The Mountain Trail Series group (meaning Dave Coblentz from Los Alamos) organized a trail run for the high country of Pecos Wilderness. The run (route shown below) climbed several of the peaks, and included some cross-country (no trails). Several of the less ambitious (I am actually always ambitious, but my athletic ambitions do not match my actual skill) chose to run a section of the course. The IDEA was to run up Santa Fe Baldy and then loop back over Lake Peak.

Map of the “course” for Beyond Baldy, a Mountain Trail Series Event. A group of us chose a slightly less ambitious versions that topped Santa Fe Baldy and Lake Peak without venturing cross country to Redondo Peak.

The forecast called for rain, but gave a glimmer of hope that the precipitation would hold off until noon. However, at the start of the run at 7 am it was clear that a storm was brewing. The Winsor Trailhead has an elevation of about 10,200′, and that is the low point of the run. The trail starts with a steep, switchback climb – about 500 feet in the first half mile – and by the top of first segment the fast runners have baked me off the end of the group. This is good because it gives me time to look at the rocks and not feel pressure. The trail is soft and not particularly rocky, but there are ample outcrops to see large blocks of granitic gneiss/schist glistening in the morning light. The schist is rich in mica – and it is a marvel to imagine that this delicate mineral could last for over a billion years!

Once the trail enters the Pecos Wilderness boundary it is fairly flat for about 4 miles. Easy running, along with a couple nice stream crossings. When you arrive at the Winsor-Nambe trail fork the serious business of climbing begins. However, today is a training run, so the pace is steady and easy. About 1/2 hour from the summit of Baldy we can see the fast runners along the ridge nearly to the top.

Standing on the summit of Santa Fe Baldy. Behind me is the silhouette of Truchas Peak and ridge, about 30 miles north. There is no sunshine this June morning.

The views from the summit of Santa Fe Baldy are usually breathtaking. However, today, hanging clouds at the front edge of a storm surround the ridges and obscures any distant vistas. There is a fine view down to Katherine Lake, which still has some ice! Lake Katherine is within a cirque on the northeast side of Baldy. This cirque was formed by alpine glaciers that were extensive about 11,000 years ago. Based on the number and character of the cirques on Baldy and Lake Peak the annual average temperature of the region must have been about 10 degrees F less than today. Katherine Lake is the largest alpine lake in the New Mexico (although small), and has an unbelievable connection to J. Robert Oppenheimer – he named it. The lake is on maps that were produced before 1930 with no name, but in 1933 a map was produced that included the name “Katherine Lake”, and a reference to Oppenheimer as the namer. It turns out that on J. Robert’s first visits to Pecos he became infatuated with a young woman of an old New Mexico family, Katherine Chaves. His affections were apparently unreturned (it would appear that Oppenheimer was a nerd as far as the opposite sex was concerned, and he may have never even approach Chaves), but on his many trips riding horses in the Pecos came to love the small lake beneath Baldy, and wistfully named it Katherine Lake.

a view from Santa Fe Baldy down to Katherine Lake. There was still a thin covering of ice on most of the lake, extremely unusual for June!

After a short break at the summit it was clear that it would soon start storming, and we began the descent down Baldy back towards Lake Peak.

Dave Zerkle on the flank of Santa Fe Baldy. Over his right shoulder is Lake Peak and the cirque that contains Nambe Lake.

Soon there was grapple falling – then hail – then rain – then hard hail. All those things are just an enjoyable part of trail running. However, they were accompanied by thunder and lightning, and it was prudent to get off the exposed ridge lines as fast as possible. At this point I am reminded that being an old, slow runner has advantages – feet close together makes for less potential drop during a close-by lightning strike!

Most lightning fatalities are NOT from direct strikes. Rather, they are from close by strikes and the fact that humans make a grounding loop. Strangely, if your feet are together the potential drop from one foot to the other is much lower than if you have a wide stance….So, run with a shuffle.

The down pour dictated a change of plans, and we had to delay the run up to Lake Peak for another day. Nevertheless, the run up Baldy is a great adventure!