Almost everything in nature, which can be supposed capable of inspiring ideas of the sublime and beautiful is here realized. Aged mountains, stupendous elevations, rolling clouds, impending rocks, verdant woods, crystal streams, the gentle rill, and the roaring torrent, all conspire to amaze, to soothe and to enrapture, Jeremy Belknap writing on the White Mountains in his book History of New Hampshire, 1793.

Silver Cascade; the southern most end of the Presidential Traverse in the White Mountains. This water fall is at Crawford Notch, a narrow gorge that is home to the Saco River. Click on any photo to get a large version.

In 1816, Philip Cardigan, the New Hampshire Secretary of State, produced the first official map of the Granite State. He wrote of the White Mountains: “The natural scenery of mountains is of greater elevation than any others in the United States; Of lakes, of cateracts, of vallies it furnishes a profusion of the sublime and the beautiful. It may be called the Switzerland of America”. Although much has changed since the dawn of the 19th century, the White Mountains remain a magical place. To a westerner, the statistics of the mountain range look pale: Mt. Washington is the high point – in fact it is the high point of the entire northeastern US at an elevation of 6,288 feet – but when you live at an elevation of nearly 7,500 feet this altitude seems pedestrian. However, that western frame of reference misleads! Mt Washington has a topographic prominence of 6,158′, which is greater than than any of the 14ers in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado. Further, the tree line for the White Mountains is about 4,300′ (2000′ below the summit of Mt. Washington) as compared to 11,600′ in the San Juans. The dominant factor in determining tree line is the average summer time temperature; Uncompahgre Peak (the high point in the San Juans) has a higher average summer temperature than Mt. Washington.

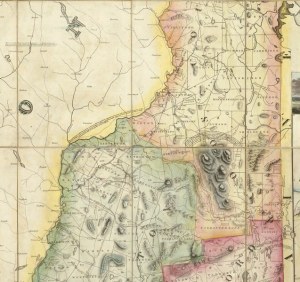

The White Mountains of New Hampshire as depicted on the “Cardigan map”, dated 1816. The Presidential Range is represented on the map by the sort of strange stack of pancakes – not a very accurate representation of the actual topography.

In the fall of 2015 I signed up for a multi-day trail run in central New Hampshire, scheduled to take place in August, 2016. Unfortunately, the trail run was cancelled, but the purchased plane tickets provided the opportunity to pursue something I have long wanted to do – hike the Presidential Traverse in the White Mountains. The Presidential Traverse is a famous thru-hike; traveling a trail from end-to-end. The Presidential Traverse (PT) is a relatively short – about 23 miles – but strenuous hike on in the Presidential Range, the northern end of the White Mountains. The “challenge” is that there is about 9,000 feet of elevation gain, most of the mileage is above tree line, lots of boulder scrambling, and only the very lucky hiker escapes extreme weather changes (in August the temperatures at the trailheads are usually in the 80s by mid-morning, but Mt. Washington often freezes, is extremely windy, and is shrouded in clouds. In 1986 the record low August temperature of 20 F was recorded!).

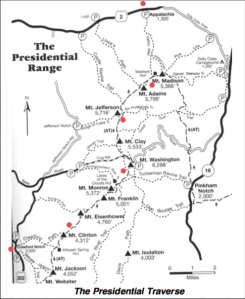

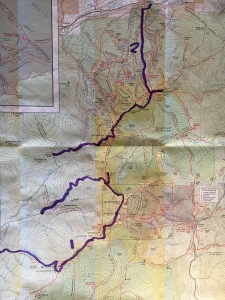

Map of the Presidential Traverse; from Hiway 302 in the south to Hiway 2 in the north it is about 23 miles (there are many trail variations). Mt. Washington is the high point, right in the middle of the traverse. The starting point has an elevation of 1,110′ and the total elevation gain is approximately 9,000 feet.

Truth be told, when the multi-day stage race was cancelled I was despondent for about an hour, and then elated with the idea of doing the PT. My first plan was to do the PT solo, and as a run. Ultra runners of my modest skill level typically complete the transect in about 10 or 11 hours (the rocky course and slippery conditions slow down even the best runners). However, my solo plan immediately tumbled into difficulty – especially the solo part. My wise and loving, but very firm, spouse vetoed the “Into the Wild” act; she volunteered to accompany me, but we would make this traverse a fast hike, not a run. Further, we would make it multi-day. The multi-day requirement was actually great – it meant more miles, more climbs, and more trails to explore. But it also meant that the chance of a “perfect” weather window was vanishingly small.

Rime ice on the summit of Mt Washington. Rime ice is formed by freezing fog that is blown by strong winds – it first freezes on an object at temperatures colder than the air, and then forms long tails in the direction of the wind.

I believe that my wife’s vision of the PT was shaped by a visit we took to Mt. Washington some 10 years ago. Hiking in Pinkham Notch we were roasted alive (80 degrees with “cut it with a knife” humidity) and eaten by mosquitos, and then froze at the summit of Mt Washington with winds “only” 70 miles per hour. I recall telling her how great it would be to battle the elements in a real storm. Mt. Washington is the deadliest mountain in the US – more than 155 people have died on the mountain since 1849. Most deaths are due to exposure (and most often that exposure is because of unexpected changes in weather or hikers that take much longer than they expect). When my wife suggested that going solo on the PT was not my wisest plan I responded with a Hunter Thompson quote: “Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming, ‘Wow! What a ride!” Seems that 60 years of life has not taught me that discretion is the better part of valor – and my Thompson quip was not received quite as intended. On the other hand, a hike along the Appalachian Trail over one of the most famous mountains in all the US was ample reward.

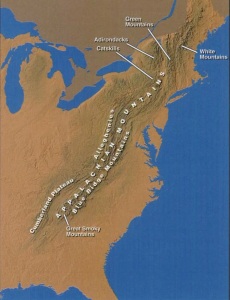

The geologic provinces of the United States. The contiguous US has a varied physiography which is largely reflective of tectonic history. There are nine major provinces, and the eastern US is dominated by the Appalachian Mountains. Despite the appearance of being a continuous mountain belt, the Appalachians have differing and distinctive tectonic histories in the north and south.

Making of the White Mountains

The White Mountains are ancient – they were formed long before the modern Rockies, the Basin and Range, or the very young Cascadia Ranges in the Pacific Northwest. Yet, despite this primordial character, the White Mountains remain an imposing landscape. Giovanni da Verrazano, an Italian explorer (and strangely forgotten map maker considering his accomplishments!) first mentioned “high interior mountains of white color” in 1524 as he sailed up the New England coast after leaving an anchorage in Narragansett Bay (the coast of modern day Rhode Island). Indeed, on a clear day, from the summit of Mt. Washington one can see landmarks 130 miles away.

The Appalachian Mountains stretch some 1500 miles from northern Alabama to Maine, and are topographic remnants of multiple continental collisions over the past 480 million years. The northern Appalachians mountains have a different record of collisions than in the south, but overall the accordion landscape is all that remains of the opening and closing of many ocean basins.

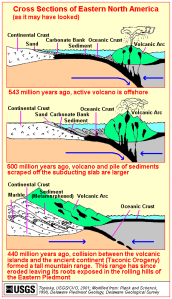

This “high” elevation was created approximately 400 million years ago, but the birth of the White Mountains began some 750 million years before the present when the first “supercontinent”, Rohinia, began to be rifted apart. Along the margin of one of the many rifts, the broad area that is today New England, became a coastal lowland on a new continental mass called Laurentia. The ancient New England coast bordered a broad ocean basin – this ocean is usually referred to as Iapetus. About 500 million years ago the ocean basin began to close due to a change in plate tectonic dynamics and the oceanic crust of Iapetus was consumed; over a time period of about 80 million years the oceanic portion of the tectonic plate was subducted beneath a growing island arc.

Cartoon of the building of the northern Appalachian Mountains from the USGS. Although there are some large scale granite intrusions in the White Mountains, the structure is dominated by collision of island arc and continental crust and the accordion like stacking of sediments and crustal fragments.

Eventually, the oceanic crust was completely subducted, and the edge of Laurentia collided with the island arc that had been formed above the subducting Iapetus plate. More correctly, Laurentia collided with a series of island arcs as the ocean basins that had been created when Rohinia disappeared, and a new supercontinent was formed over a 150 million year period. These collisions compressed, faulted, folded the converging crustal fragments and created a series of high mountain ranges. The first collision and subsequent mountain building episode is called the Taconic Orogeny (the name comes from Taconic Mountains in New York and Vermont). The White Mountains were a direct result of this collision, which also accounts for most of the rock types that are seen along the Presidential Traverse today. Unlike the San Juan Mountains in Colorado, there was little volcanism (although there was some) involved in the original mountain building. The rocks that are mostly seen in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains are metamorphic – the Laurentia crust and Iapetus ocean sediments that have been squeezed, buried, heated and occasionally melted.

Although other continental collisions and rifting events occurred after the Taconic Orogeny, the geology of the White Mountains was largely set by about 400 million years ago. By the way, the zone of collision was much larger than what one sees today. The Caledonides Mountains of Scotland and Ireland are really the siamese twin of the White Mountains – accreted onto the edge of Laurentia. 380 million years ago it would have been possible to hike from Mt. Washington to the Cairngorm mountains (south of Inverness). Eventually the collisions assembled a new supercontinent, Pangea.

Notional map of Pangea, circa 275 million years before the present. Almost all the landmasses recognized as continents today were temporarily assembled into one large “super continent”. Around 185 million years ago, Pangea began to break apart along rifts and the modern ocean basins began to form.

Around 185 million years ago Pangea began to break up – rifts criss-crossed the giant continent, and Pangea was slowly pulled apart. The “pulling apart” created new oceans, and Pangea was diced into continental fragments that would become our modern continents. One of the rifts developed east of what is now New England, and the Atlantic ocean slowly opened. This rifting process brought hot mantle rocks closer to the Earth’s surface, and wide-scale melting of the lower crust was common. This melting produces large granitic plutons – that may, or may not, have had volcanic vents at the surface. Either way, the granitic plutons were hot and buoyant, and caused the White Mountains to rise in elevation. By 160 million years ago the crustal melting had ceased; the rock building history of the White Mountains ended. It is possible to find the granites associated with the opening of the Atlantic, but they are mostly “beneath” the Presidential Traverse, and exposed in the incised canyons,which are known locally as the “Notches”.

Although the geology and elevation of the White Mountains was the result of very ancient collisions and rifts, the present day topography was carved by a much more recent phenomena, glaciation. Geologist define the Pleistocene epoch (the period of time from 2.6 mya to 11,500 before the present) as a time of massive glaciation in the Northern Hemisphere. The glaciation – or more correctly, the cold climate – was episodic, and the White Mountains were occasionally completely covered by a thick ice sheet (not unlike Greenland today). The most recent “ice age”, referred to as the Wisconsin, started about 80,000 years ago. The Wisconsin age produced an ice sheet called the Laurentide; about 30,000 years ago the White Mountains were about 1 km beneath the ice of the Laurentide.

A map of the major alpine glaciers that carved the Presidential Range (map from Goldthwait, 1970). There are nine glaciers which are indicated by the gray regions. The largest was north of Mt. Washington and carved a cirque and glacial valley known as the “Great Gulf”

The Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated as the climate warmed, and exposed the White Mountains again about 13,000 years ago. However, as the ice sheet retreated, alpine glaciers developed and carved cirques and U-shaped valleys that give the present Presidential Range its character. The figure above shows the location of the 9 most prominent glaciers in the area been based on the geomorphic signatures seen today.

A large glacial erratic in Franconia Notch in the White Mountains. This boulder was moved some 200 miles from the north by glacial ice, probably about 30,000 years ago. It is named after a teamster that sought shelter beneath the rock’s overhang during a blizzard in the early 1800s.

The rugged topography of the White Mountains is only a part of the challenge of any hike or run across the Presidential Traverse. Much of the fame of the White Mountains, and Mt. Washington in particular, is associated with its weather – it is often called “Home of the World’s Worst Weather.” The sobriquet is well earned even if many want to quibble with the definition of worst. Mt. Washington towers above the surrounding New Hampshire landscape, and by elevation rise alone has temperatures 30 or 50 degrees F cooler than the trailheads leading up to the Presidential Traverse. Add in the fact that on average, the Mt Washington experiences winds in excess of 75 miles per hour on 110 days every year, and it can be a very cold place. The lowest recorded temperature on Mt. Washington was -50 F (January 22, 1885), and the lowest recorded wind chill reading was -103 F (January 16, 2004)!

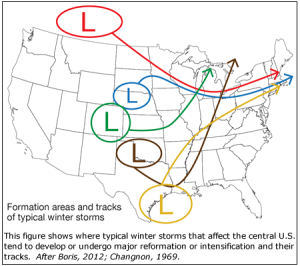

Major storm tracks for the US – storms form in the west and “track” across the continent, usually strengthening. Three of typical tracks (the red below is known as the Alberta Clipper, the blue is called the Pacific, and the light red is called the Texas) converge on the Northeast – the White Mountains are in bull’s eye of storms for the entire year.

The weather conditions of the White Mountains are controlled by three things: (1) the mountains are at the convergence of three major storm tracks, (2) the mountains are oriented north-south and provide a significant block to the predominate winds from the west, and (3) many low pressure systems are created off the New England coast due to the significant temperature difference between the landmass and the Atlantic ocean (these low pressure systems “suck” air across the White Mountains). All three of these factors contribute to wind, and wind over mountains creates precipitation. Air cools as it passes up and over high terrain; as the air cools it loses it ability to hold moisture (first forming clouds or fog, and then rain and snow – this is called the Foehn effect). Mt. Washington receives the equivalent of 97 inches of rain every year (“equivalent” because Mt. Washington receives 280 inches of snow every year!). No season is spared the winds or precipitation – clouds shroud the top of Mt. Washington 60 percent of the time!

A view of the summit of Mt. Washington (8/12/16). I am standing about 10′ from the sign, and the visibility is not just different…the wind was blowing more than 45 miles per hour, and less than 90 minutes later a monster rain/hail storm would deluge the southern Presidential range. Hiking the Presidential is as much about weather as it is tough trails.

The White Mountains are both a geologic marvel, and a most amazing coincidence of circumstances with regards to weather patterns. Darby Field, a 32 year old ferry operator is reputed to have been the first recorded person to climb Mt. Washington in 1642. I say reputed because academics love to argue if Field actually climbed to the top, or even climbed at all. However, the Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, recorded an interview with Darby that appears remarkably consistent with the geography. It is hard to image what that first ascent was like; primitive gear, no appreciation for the weather changes, and likely no real planning for the ascent. However, if Field could make it to the top, then clearly a modern man armed with geologic knowledge, an keen eye for weather, and lots of snacks in a pack could cross the Presidential Traverse!

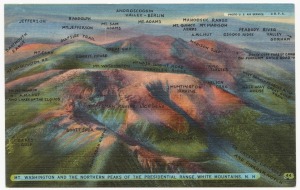

Artistic rendition of the northern Presidential Range (postcard circa 1930). Mt Washington, in the center of the image, has an elevation of 6289′; the surrounding valley floors are on the order of 1000′.

Touching the Presidents

I arrived in New Hampshire with a plan for a 3-day hike (well, I was originally optimistic that I would be running some of the course – the trails and weather proved a far stronger force than personal optimism) in the White Mountains. Day 1 was a “warm up” with a 9 mile loop near Franconia Notch; climbing up from the floor of the notch (elevation 1900′) to Haystack (elevation 4780′) crossing the Franconia Ridge to Lincoln (elevation 5089′) and on to Lafayette (elevation 5249′ ) before descending back to the floor. The Franconia Range is southwest of the Presidential Range within the White Mountains, and most of the rocks that are exposed are younger in age – primarily the granites associated with the breakup of Pangea. The notch is a very narrow slice through the Franconia, and is perhaps most famous for a rock formation that looked resembled the profile of an old man (called Old Man of the Mountain). Unfortunately, the rock formation collapsed in 2003 but not before the profile graced all the state hiway signs in New Hampshire and the backside of the US quarter commemorating the state (the perils of being famous for rocks….).

The ascent up the Mt. Lincoln Loop is along the Falling Waters Trail – homage to the numerous waterfalls on the first half of the climb.

The hike up to the Franconia Ridge is quite rugged – it is steep, rocky, and occasionally slippery. It is also the arch-type White Mountain trail. It was constructed in the 19th century and basically goes straight up; no switchbacks, no much taking advantage of contours. In places the trail is a smoothed path, but mostly it is a hiway of rounded boulders varying in size from a few inches to several feet. Quad busting, ankle biting rocks. I did see a couple of people “running” this section of the trail, but it looking more like hippos trying to get out of a water hole.

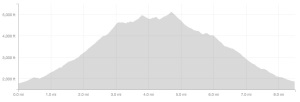

The profile for the Mt. Lincoln loop. The high peak in the middle of the profile is Mt. Lincoln, and the high point is Lafayette. The 3 mile climb to the ridge is a constant 15-35% grade.

It was a warm day (it was 82 degrees at the trailhead at 8:00 am), and it took us about 2 1/2 hours to arrive at Haystack. It is a bit strange to be a few hundred feet about treeline, yet only at 4700′ elevation. However, we were rewarded with great views – although the humidity limited the crispness of horizon.

Across from Haystack is Cannon Mountain, which is the former “home” of the Old Man of the Mountain. Cannon has an elevation of a little more than 4000′, and its most pronounced feature is a huge wall of exfoliating granite.

View fromHaystack across the Franconia Notch to Cannon Mountain. The large exposure of rock is exfoliating granite – which also created the Old Man of the Mountain.

Once on Haystack the trail follows Franconia Ridge, and is mostly class 1 (maybe a class 2 section here and there). There are many articles that describe the Ridge as a “knife edge”, but compared to the Knife Edge on Capitol Peak in Colorado, Franconia Ridge is a freeway.

View from Haystack to Mt. Lincoln and Franconia Ridge. I really had to do this loop to get Mt. Lincoln – the greatest President, and did not want to disrespect him in any run of the “Presidential Traverse”.

I was hoping for a good view of the Presidential Range from Lafayette, but the haze associated with the humidity precluded an impressive visa of “towering” Mt. Washington. It was hard to imagine that a major series of storm cells was moving into the area, and by tomorrow the weather would be rain.

The summit of Mt. Lafayette. In the distance is the northern part of the Presidential Range. It is a tough 4 mile slog down with 3400′ drop in elevation.

The descent down Mt. Lafayette to the Franconia Trailhead is a slog. It is a rocky trail, following the now familiar White Mountain tradition of vertical profiles and lots of boulders. Michelle struggled with the descent – the trail taxes the small muscles that stabilize knees and hips (and not something that one strengthens by running road marathons). By the end of the day she declares that she is done with these crazy hikes, and I am back to doing the Presidential Traverse solo, although supported.

I awoke early Friday morning (8/12/16) ready to run the southern PT. I studied the radar images long and hard – somehow I convinced myself that the storm track was mostly north of Mt. Washington, and I was going to have a miracle hike. Self delusion is an important skill for ultra runners – only equalled by the importance of a very short memory for pain and discomfort. I was on the trail by 6:15 am; I took the Jewel Trail up from near the Cog Train station. The trailhead had a temperature of 67 degrees and it was muggy. I could not see Mt. Washington because it was shrouded in thick fog. The climb from the trailhead to Mt. Washington is about 5 miles and a gain in elevation of 3800′ (most of that gain is in the first 2.8 miles).

A view from the Jewel Trail at an elevation of 4200′ feet (just about treeline) towards the southern PT. The distance ridgeline is Monroe, Franklin, and the final “hump” is Eisenhower. The dark skies were a harbinger of things to come.

The PT is one of the classic American mountain routes – it was first done in September of 1882 by a pair of hikers, George Sargent and Eugene Cook. They hiked the PT from north to south in about 20 hours, and since that time thousands have accomplished this feat. The fastest known time for the traverse was made by Ben Nephew in 2013; only took him 4hr and 33 minutes! I had no illusions about being “fast”, and after taking 2hrs 30 minutes to get the five miles to Mt. Washington I was pretty sure the FKT is fiction!

Above 4,400 the fog rolled in and the wind began to roar. The visibility was 10s of feet by 5,000 feet elevation. The trail is marked with cairns which is the only way to not get lost. Along the trail are large blocks of white bull quartz – eerie ghosts in the fog.

The climb up Jewel Trail is very bucolic and although steep it probably is “runnable” to my colleagues back home. The path passes through several ecological zones. The trail starts in hard wood forest, and within about 1 mile and 1,000 feet elevation gain the vegetation is dominated by spruce and fir trees. The tree line is around 4,200 feet, and the ground is covered with a dwarf spruce called kummholtz; after 4,400 feet there is only moss on the rock. By 4,400′ feet elevation the visibility on this day is only a few 10s of feet, and the wind is ferocious. The trail in the alpine zone is not really a path, but a marked course through a rough jumble of rocks. The course marking is done with cairns – mostly 3 to 5 feet tall, every 10 to 20 yards. Even at that close spacing I find myself searching for the next cairn before venturing forward. Along the way I see large blocks of bright white quartz scattered about, created during extreme metamorphism of the Taconic orogeny. Often the keepers of the cairns have placed a block of this quartz on top of the rock piles, and they look like lighthouses in the stormy weather. There also is some whimsy – several of the blocks have been carefully spray painted with gold metallic paint to look like nuggets of gold (a common association for the gold deposits of the western US). I am not fooled, but very amused!

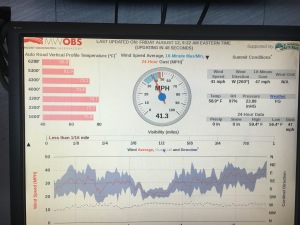

A large video display greets guests at the top of Mt. Washington. It shows the temperatures on the way up the mountain, the wind speed, and the precipitation. For my journey the wind speeds gusted to 55 miles per hour, and were steady at about 45 miles per hour. Later in the day they would reach 75 miles an hour.

I arrived at the summit a few minutes before 9 am. The visibility is near zero, and the wind is really blowing, but it is not really cold – and most importantly, it is not raining or snowing. Except for the employees, the summit is deserted before 9. To understand the significance of the “deserted”, it is important to realize that Mt. Washington is the equivalent to Pikes Peak in Colorado. There is an auto road to the top as well as a cog railway bringing tourists in flip flops and tee shirts to experience the “worst weather in the world”. Annually about 250,000 people visit the summit (only about 12,000 hikers – and those hikers often have short tours near the summit). I am meeting Michelle at 9:30 for some previsions and a check on my progress. By 9:30 the tour vans and trains begin to arrive, and their are at least 100 people freezing their asses off getting a photograph at the summit sign. In someways this seemed truly surreal.

The heavy fog and traffic coming up the mountain delays the arrival of Michelle and I getting very nervous. There is a large video display of the weather radar, and it is clear that some nasty cells are soon to arrive. I finally get on the trail about 10 am, and start down the Crawford Path toward Mt. Monroe. The Crawford path runs the entire length of the southern PT (about 8 miles) and is the oldest trail in the US. The trail was started by a Abel Crawford and son in 1819, and finished to the top of Mt. Washington in 1840. Abel Crawford made the first ascent on the trail via horseback (!!) when he was 75 years old. As I start down the trail, it is rocky, but one of the best in the White Mountains. 30 minutes into the descent the winds increase, and everything becomes wet. The rocks on the trail become first slippery, and then down right treacherous. I can’t run because every step is an opportunity to stumble. In fact, after about 1.5 miles descent I slip in the most precarious fashion – my right foot slips forward and my left knee is completely bent such that the back of my calf is touching my buttocks. I have not bent like that since age 3 – I have the flexibility of dried wood in my ligaments. In 2009 I had my right knee replaced and 2 months after surgery I was not getting the range of motion that I needed for full recovery. This was “fixed” by a procedure called manipulation under anesthesia, or MUA. MUA is ugly – after knocking you out the Dr. brutally flexes and bends your leg to break all the scar tissue that developed after surgery. When you awaken your leg is black and blue, and it hurts like hell. Well, the Crawford Path performed MUA on my left leg….just without the anesthesia. However, there is no time to curse the misfortunate because the weather is getting worse.

I am sore, but able to slowly build pace, and arrive at the Lake of the Clouds which is located some 1200′ in elevation below the summit. The lake is reputed to be quite picturesque – but I don’t really know as Lake of the Clouds was in the clouds. I did use the water of the lake to clean the scraps on my knee, but I mostly thought about King Arthur and Lady of the Lake. Alas, no one arose from the water with an excalibur for me. The lake is in saddle between Mt. Washington and Mt. Monroe, so shortly after passing the lake (and passing by the Lake of the Clouds hut filled with people waiting out the storm) I have another climb. It is dark now even though it is only around noon. The wind is howling, and I am mostly hoping just for completion of my journey.

I arrived at Monroe (elevation 5371′), and I hear a very distant rumble – I think thunder! The descent down Monroe is pretty easy, and the next section of the trail to Mt. Franklin is actually runnable – and I run as fast as I can. I pass three different groups of hikers coming up the trail, and offer my advice and condolences. More thunder, and it is 2 hours since I left Mt. Washington. I sprint up Mt. Eisenhower (one of my favorite presidents, BTW – very underrated, but anyone that calls out the military industrial complex deserves kudos), and arrive at 2hrs 31 minutes since summit. Eisenhower is only 4760′ elevation, but it quickly becomes the eye of a storm. Thunder is all around, and sheets of rain begin to fall. The rain does not last long – because it turns to hail driven by 50+ mile per hour wind. I realize I am in trouble and bushwhack down the leeward side of the mountain and crawl into a small opening within a pile of rocks and wait out the storm. After about 30 minutes the thunder ceases, and the rain/hail becomes a thick mist. I decide to bail off the PT ridge and head for the valley below. I am disappointed – I came very close to finishing the southern PT, only missing Mt. Pearce. I justify not visiting Pearce because he really wasn’t much of a president – he signed the so called Kansas-Nebraska act that enforced the capture of any fugitive slave in the 1850s.

The Edmonds Trail after the storm – water, sometimes knee deep running in the channel carved by 100s of thousands of hikers over the last 200 year.

The hike of the southern PT amounted to a 11.4 mile jaunt with 5,130′ elevation gain. The storm was epic – and certainly by early evening I was marveling at my survival. Well, really, just happy to say the southern Presidentials were done.

Day three of the White Mountain adventure started auspiciously – I arose at 5 am hoping to be on the trail to climb the northern PT by 6 am. The northern PT is infamous for it rocky trails, and I knew I was in for a long day even if the planned route was only 9 miles and 3,600′ elevation gain. However, at 5 am it was raining; if it was raining at 1,000′ elevation what was it doing up on Mt. Jefferson (elevation 5,712′)? Depressed, and sore from my slips the previous day, I pondered my options. Thankfully, Michelle counseled patience, and indeed the rain lifted by 6:30, and I was able to get to the Caps Ridge trailhead by 7:30. Caps Ridge is a relatively high trail that travels straight up to Mt. Jefferson, the third highest peak in the PT. However, it is not a “normal” trail – the last 1 1/2 miles to the summit of Jefferson is a fully exposed scramble. Dicey in the best of times, but slick with rain and in the fog was “beyond epic”.

The view from the Caps Ridge trail towards the ridgeline of the southern PT. There are two layers of fog – one on the valley floor and the second at 4,300′. That higher altitude layer would be a constant companion for the entire northern PT.

Although I had researched the Caps Ridge trail I was surprised how difficult it was – more slimy than slippery, and I slipped and slid many times. The scramble would have been exciting another time, but being alone, far from “help”, my heart was working overtime.

The beginning of the upper part of the Caps Ridge trail at about 4,200 feet elevation. Not a particularly welcome sight for someone that has no flexibility.

I was concerned that my flexed knee from the previous day would be a problem, but in fact it was just sore and not particularly stiff. The scramble to the top of Jefferson was one of the hardest things I have done in years. I banged my right knee, opening a pre-existing scab. Blood pored forth, but there was no pain, so except for the fact that I looked like the “living dead” I was able to finally get to the top of Jefferson after 2hrs and 20 minutes.

The summit of Jefferson. Just a pile of rocks in the fog. This is pretty much how Adams and Madison looked later in the hike, so I need not add photos of those summits.

Cell phone coverage was perfect on Jefferson, so I texted Michelle and told her that I was on course for a 3:30 arrival at Appalachia Way. Little did I know that my views of 10′ feet or so into the fog were among the best I would have for the entire day. I had visions of magnificent panorama of the Great Gulf, the huge, deep glacial cirque only a few hundred yards from the summit. Instead, I had to settle for my imagination, and the very strong desire just to plow through. The trail from Jefferson to Adams is called the Gulf Way, and it is truly my least favorite trail in the entire world. It is just a bunch of boulders, all waiting to cause me to slip. I took over an hour to cross the 1.5 miles to Mt Adams (elevation 5793′ – second highest in the PT). Mt. Adams turns out to be just a tall stack of boulders. I found no outcrop what so ever. If a mountain could ever be called ugly, surely Adams earned that moniker.

The trip over to the final peak on the northern PT, Madison, was uneventful if slow. I was running on determination, and not really enjoying the adventure. Tagging the top of Madison sent a wave of relief over my soul, and I realized all I had to do was descend 3.8 miles and 3,500′. The first 2000′ of descent were slow, but once I entered the hardwood forest the canopy provided protection from the rain, and it was possible to maintain a decent pace.

I finished the hike in a little under seven hours (for 9.2 miles…yes, a blistering 1.3 mile an hour pace). It was a true adventure: 3 days, 31.7 miles, 13,932′ elevation gain. I missed the vistas, but I also missed the crowds that had the sense not to be on the mountain in stormy weather.

The PT routes – day 1 and day 2. Just lines on a map now, but adventures in the fog when on the trail

It aint the Rockies

Hiking in the White Mountains is fundamentally different that running and hiking in the Rockies. The trails are just different. All the trails in the White Mountains were laid out in the 18th and 19th centuries, and simply were straight lines between point A and point B. No switchbacks, no grooming. I am sure that there are many talented runners and hikers that can hop from rock to rock and travel the Presidential Traverse with ease. I am not one of those. However, the PT was an adventure – in some ways it was exactly what I crave. A challenge physically, a competition with nature, and a deep sense of history. Just no pictures – the fog rules the day.