Geology is the study of pressure and time. That’s all it takes really, pressure, and time. Comments by Red in The Shawshank Redemption (1994).

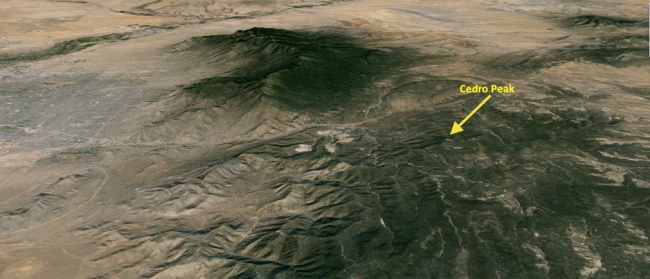

A Google Earth view looking north along the crest of the Manzano and Sandia Mountains, just to the east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Sandia and Manzano mountains are a 75 km long north-south, and are the uplifted shoulder of the Rio Grande Rift. The Sandia and Manzano mountains are separated by the Tijeras Canyon which provides the passage for interstate 25. The Cedro Ultra is a race along the flank of the Manzanos and climbs to the top of a limestone hill, Cedro Peak.

One of the most iconic landscapes for New Mexico is the Sandia and Manzano Mountains towering to the east of the Rio Grande Valley in Albuquerque, our state’s largest city. The elevation of the Rio Grande in Albuquerque is a little more than 4900 feet, and the high point of the Sandias is 10,678 feet. This elevation prominence is expressed in dramatic fashion due to the steep westward facing scarp of the Sandia-Manzano mountains – which is actually the bounding fault that uplifted the mountains beginning some 10 million years ago. The view looking from the city to the moutains in the east is one that looks like a layered cake. The core of the range is Precambrian granite that is 1.5 billion years old, overlain by a light colored, flat lying limestones that are 300 million years old.

The Sandia Mountains as dusk – the pale red color of the 1.5 billion year old granite is source of the mountains namesake, the spanish word for watermelon. The top hundred meters is the light colored, 300 million year old limestone. The gap in ages between the rocks, 1.2 billion years, is called the Great Unconformity

The backside of the Sandia-Manzano mountains have a relatively gently dipping topography with rolling hills. When I was planning my training for the 2014 Jemez Trail Run I wanted a long “tune up race”, and the Cedro Peak 45 km run looked like a perfect opportunity. Cedro Peak is just south of Tijeras Canyon, a narrow valley that separates the Sandia and Manzano mountains. I did not know much about the Cedro Peak run except that it was in a place I liked, and reports are that it was “faster” than the Jemez Trail Runs. I have long ago given up on the idea that I would ever be a fast trail runner. I simply don’t have the athletic ability to run miles and miles of sub 9-minute miles on rocky and uneven trails, and age is beginning to really fossilize my body. However, I really love being out on trails, and find great happiness climbing and descending hills and smelling the desert foliage. The last time I had been to area around Cedro Peak was as an undergraduate student in the mid-1970s on a Historical Geology field trip. We collected trilobites within a mile or two of the race course – in fact I suspected that I would be tripping over ancient marine life in the 45 km of running!

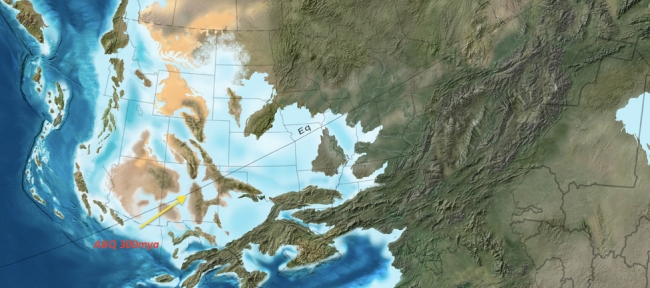

The geography of what will become North America 300 million years ago. There is a large continental mass to the east of the ancient New Mexico, and a shallow sea along with a few islands covered New Mexico. The Sandia and Manzano mountains were part of this shallow sea, and this Pennsylvanian Ocean (Pennsylvanian refers to a geologic era) was teaming with primitive life.

The Geology of Cedro Peak

Perhaps because I run with my head down and move pretty slowly, I am always dissecting the geology of a trail run. The Cedro Peak ultra is no different; most of the rocks that are along the 45 km of trail are ancient limestones and tell the story of a shallow, warm sea that existed for a 100 million years surrounding a system of equatorial islands. The figure above provides a guess at what the region that will becomes the western US looked like about 300 million years ago during the geologic epoch known as the Carboniferous (360 to 300 mya). On a little finer resolution, rocks that pave the Cedro run are from what geologist call the Pennsylvanian period.

In the figure you can see the light outlines of the New Mexico – very near Albuquerque was the western shore of a large island. This island had been above sea level for more than 1.2 billion years, slowly eroding away. Also on the map is a projection of the equator during this time, and Albuquerque was the equivalent to the modern day Galapagos Islands – spot on the 0o latitude. Life, both plant and animal, was very different 300 million years ago. Amphibians were the main land creatures, and they did not venture far from the ocean.

The ocean surrounding the island was not unlike the Florida Keys today. The waters were rich with life that utilized photosynthesis for growth, which, in turn, took carbon out of the atmosphere and produced carbonate (CO3) for their skeletons and shells. When these organisms died their remains accumulated in giant graveyards and slowly compressed and made limestone. To paraphrase from the The Shawshank Redemption, time and pressure turned the graveyard into a distinctive rock that will last more than a quarter of a billion years. The limestones in the Manzano mountains are known by several names, but the most generic and common is the “Madera Limestone”. Most of the rock beneath the racers feet in the Cedro Peak ultra is Madera limestone, and if one looks closely at any cobble it can be seen that it is filled with fossils, the skeletal remains of creatures that lived 300 million years ago.

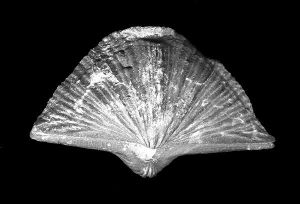

Brachiopod from the Madera Limestone (collected in the Jemez Mountains, late 1960s). This is the hard shell on the “head” of a marine worm.

I collected many fossils from the Madera Limestone – although not the Sandia-Manzano Mountains, but instead a small outcrop in San Diego Canyon, north of Jemez Springs in the Jemez mountains. The fossils in the Jemez are identical to those in the Manzanos with one notable exception – trilobites. There are more than 90 taxa of fossils in the Madera; most of these are brachiopods and gastropods. The picture above is a Jemez brachiopod I collected in the late 1960s. It looks like a modern mollusk, but it is not! There are actually brachiopods alive today (very rare), and they are marine worms. In the Pennsylvanian times brachiopods dominated the shallow marine environment.

The first person to systematically collect and describe the fossils from the Madera Limestone was Jules Marcou, an extraordinary French geologist and paleotologist. In 1853 Marcou published a map, Geological Map of the United States, and the British Provinces of North America, followed up by a book entitled Geology of North America. These works were panned by the giants in American Geology at the time – including Dana, the father of American mineralogy, but Marcou did get much of the relative dating of geologic beds correct, including the Madera Limestone.

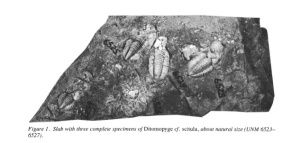

Trilobites from Cedro Canyon, not far from the path of the Cedro Peak Ultra. Trilobites walked on the ocean bottom and swam short distances; they regularly molted their hard shells, which accounts for the clusters of fossils within small areas.

I first visited the region around Cedro Peak as an undergraduate student in the mid-1970s on a historical geology field trip. The reason for the trip was to visit Madera Limestone, and we ventured up Cedro Canyon, located just south and west of the peak. About 2 miles from the peak is one of the most famous New Mexico fossil localities – the Cedro Canyon Trilobite beds. Trilobites are one of the most successful life forms ever, and even though they became extinct before the first dinosaur walked the Earth they had flourished for 270 million years! Many evolutionary biologists consider them the foundation of all complex land based life forms today. Trilobites are the earliest arthropods, and are a hard shelled creature with many body segments and a large number of jointed legs – they sort of look like a cross between cockroaches and centipedes. Trilobites are relatively uncommon Pennsylvanian rocks, but this single locality in Cedro Canyon has produced hundreds of fossils. The picture above is a well-fossilized group in the University of New Mexico collection. I was thinking of visited the locality after the race on April 12, but I was toast after the run – and I used the excuse that since my visit 38 years ago many fossil collectors have picked through the outcrop, and I would have came up empty handed!

Standing at the start line about 23 minutes before 7 am, April 12. The weather is near perfect, and the race was afoot!

The Run

One of the joys of running an ultra trail run is that each is different, the runners and race volunteers are mellow, and there is always something funky. The Cedro Ultra is put on by the Albuquerque Road Runners, and has two options – a 45 km out-and-back, and a 45 miler. It is a relatively small (or more correctly, intimate) race, with about 80 people in the 45 km, and 60 in the longer course. Packet pickup is at an older hotel in Albuquerque near the intersection of I-25 and I-40 (which is known as the “Big-I”). I arrived on Friday about 5 pm to pick up my packet, and was a little surprised (and probably a little intimidated) to find the parking lot filled with motorcycles and black leather. The hotel was also hosting a get together for a veterans biker group. At the entrance to the hotel lobby is a large stone tablet inscribed with the Ten Commandments — as I said, all trail runs have their version of funk.

Check-in was uneventful – everyone is helpful, and the runners checking in are, as always, filled with optimism about the next day’s run. I inquired if there was a special category for runner with at least two prosthetics, and as usual, my question was met with blank stares. It is obvious that I will never actually place in a race based on age group, so I am looking for a way to win some hardware based on my artificial joints. Alas, I am not going be in the running for any recognition at the Cedro Peak ultra.

The 45 km race is slated to start at the Oak Flat campground south of Tijeras at 7am. It is about a 25 minute drive from downtown Albuquerque to the campground, so we (my wife drove me down) arrived about 6:30. The weather is perfect – temperature was 46 degrees, there was light cloud cover, and a gentle breeze. The starting line is situated at about 7700 feet elevation, and in a nice groove of Ponderosa Pines and Gamble’s Oaks. Ponderosa Pine have a range of about 7000 to 8500 feet elevation in New Mexico, and the starting point reminds me much of my home in Los Alamos. The volunteers for the race are friendly and helpful, and I know a few of the runners gathering for the race. The start at 7 o’clock is low key, and about 80 runners quickly funnel onto a nice single track trail.

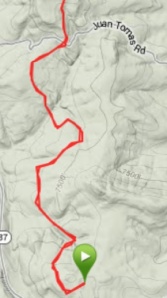

GPS track from my garmin for the first (and last) 5 miles of the Cedro Peak course. The trail descends some 350 over the first 1.5 miles making for a fast start. The first aid station is at the intersection for Juan Tomas road.

Although this may have been a tropical beach 300 million years ago, today it resembles nothing “oceanic”. The course follows a soft trail for about 2 miles with minimal rocks, and drops in elevation about 350 feet. This makes for a very fast start, and spreads out the pack. I am able to easily keep my pace at 11 mins/mile for the first 4.5 miles, and am feeling great. The drop in elevation takes us out of the Ponderosa into Pinyon-Juniper forest. Pinyon-Juniper is the defining forest cover for the high New Mexico desert (elevations of 6000-7500 feet). The problem with Pinyon-Juniper forest is that Juniper trees are prolific pollinators, and April is within the period of spewing out a strong allergen. I am not alone among the runners with a dripping nose by the first aid station located about 4.5 miles from the start. Junipers are a variety of cedar, and it is this tree name that gives Cedro Peak its name (cedro is spanish for cedar).

The second part of the out-and-back course, from the first aid station, summiting Cedro Peak, and going to a turn around to the west. The course follows a high ridge line before diving down into a canyon.

Beyond the first aid station the course follows a ridge line that ascends to 7800 feet elevation, the high point along the course. The trail now has much more exposed geology – i.e., rocks and cobbles. It is all gray limestone, which erodes as sharp and angular fragments that are unforgiving to ankles. The entire region, from start to finish is criss crossed with many trails. Fortunately, the race crew has done an outstanding job of flagging the course (and I am quite thankful that in places they over flagged because when I was coming back I was tired and alone, and easily confused at every intersection!). At mile 6 the trail drops off the ridge line for a rapid descent into a canyon. I am not very good at steep descents, and fear for a bad stumble. However, my phobia is not shared by many of the younger races who just fly past me hopping from rock to rock. After the 1.75 mile descent, the course is rolling until aid station 2, located at the base of Cedro Peak. I am more or less running with a group of about 10 people into the aid station. I pass most of the people on the uphill sections, and get passed on the downhill or flats. The second aid station is located about 11.9 miles from the start, and just as I am coming into the aid station I get passed by the first runners on their way back to the start line (that means they are at mile 16 when I am at mile 12). I have to admit that the fast runners look much fresher and better than I do even though I am way behind them.

Elevation Profile along the Cedro Peak Ultra. The course is an out and back, so the climbing is “symmetric”. The killer climb starts after 20 miles – between mile 21 and 21.7 you climb about 600 feet, so the grade is above 15%

At the Cedro Peak aid station I am feeling pretty strong, and fuel up on some of the best home made chocolate chip cookies that I have ever eaten. The course elevation profile (from my garmin) is shown in the figure above. The profile is symmetric reflecting the out-and-back course. The sharp climb from miles 12 to 13 is ascent of Cedro Peak. This is walking territory for me — not too difficult, but no sense in running up this hill. The top of the hill is covered with telecommunication equipment, and too my surprise, it is yellow with spring flower blooms.

Cedro Peak is a prominent point in the area, and is used for communications towers. The top was covered with spring flowers – a splash of yellow in the other wise drab Pinon-Juniper forest.

The climb up Cedro peak brings a relief from the monotony of gray limestone cobbles and blocks. The top of the peak has an exposure of the Burson formation, which marks the retreat of the ocean from the surrounding island, and the limestone is replaced by rocks deposited on land. The rocks becomes interbedded black shales and some red sandstones that are detrital (erosional) fragments cemented by authigenic quartz. The sandstones are a beautiful pink-bed, and sparkle in the mid-morning sun. The sandstones and shales are a signature of alternating swamps and dry alluvial dunes during a period of time lasting a few million years. Once at the top of Cedro Peak it is a quick descent to a service road and a plod of about a mile to the course turn-around. I am still pretty much with the same 10 people, although I am definitely beginning to tire. I reach the turn around (14 miles) at just under 3 hrs, right on the pace I had wanted.

The turn around is mentally challenging — it is nice to be heading towards the finish line, but I can remember the big climbs to come. First, up Cedro Peak (another walk), down to the aid station (all the chocolate chip cookies are gone! how can that be?), and then only 12 miles to go. My group is beginning to stretch, and I am definitely taking up the rear. The rolling hills are just drudgery but not too difficult. Then, mile 21 – the “hill”. I can see three runners in front of me on the start of the steep ascent, but within 5 minutes I see no one! This is a steep section, and using my garmin I calculate that there are sections of the grade that are approaching 20 percent, and the entire mile (mile 21 to mile 22) averages just under 15%). I feel okay, but I am going so slow. It takes me 24 minutes to climb the mile up the hill! By now I am totally alone, and I am wondering if I made a wrong turn (of course not, the race organizers have done a great job marking the course).

At the top of the ridge I try to speed up, but there seems to be a disconnect between my brain and my legs. I feel okay, and I am not breathing hard; however, my legs are ignoring the command to start a more rapid turn over. I begin to wonder if my artificial hip and knee have some kind of computer chip that has been hacked by Russia cyber criminals with a denial of service attack. This thought is delusional of course, because my hip was replaced when Yeltsin was president, and surely the Russians did not have that capability then….. I simply can’t run any faster than about 16 mins/mile. However, the slow pace has a benefit — I begin to see and identify fossils in the limestone rocks. I see lots of crinoids, a couple of brachiopods, and lots of unknown shell fragments. I don’t stop to pick them up because I fear that I will never be able to start running again, but I plan a future trip here with my grandkids to collect fossils.

At the last aid station I drink a half dozen cups of coke, and eat some potato chips. There are 12 people manning the aid station, and I am the only runner there. I think they are waiting for me to move on so they can go home. The last 4.5 miles is painfully slow but the climb up 350 feet really is not difficult. I am alone until the last 500 yards when I am caught by another runner, but is polite enough not to race past me at the finish line.

I finish in over 7 hours, meaning it took me more than 4 hours to run the return 14 miles. I am quite disappointed with my time, but on the other hand I enjoyed the course. I can’t really say why I transformed into a slug, but hopefully this will help prepare me for the Jemez Trail Run in a month. There is a wonderful band playing at the finish line, and the hosts have a nice grill. I can’t eat for at least an hour after running, so the food is not for me — but that is a mute point any way as the reward for an ultra run is going to Maria’s in Santa Fe and feasting on carne adovada.

The Cedro Peak ultra is a nice, well run race. As the Shawshank Redemption quote says — all it takes is pressure and time. A New Mexico treasure less well known.