A man on foot, on horseback or on a bicycle will see more, feel more, enjoy more in one mile than the motorized tourists can in a hundred miles – Edward Abbey, in Desert Solitaire

Looking north across the Tucson Basin in southern Arizona. The El Tour de Tucson is one of the largest biking events in the country – nearly 10,000 riders circle around the “Old Pueblo”.

I moved to Tucson late in the summer of 1983 to become an Assistant Professor of Geosciences at the University of Arizona. I spent 20 years in the “Old Pueblo” and lived the academic life, became curator of an outstanding mineral museum, worked on the greatest mineral show in the world (the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show), met my future wife, raised my family and saw my son become a third generation Eagle Scout. The Sonora Desert is like a cactus in bloom – beautiful but also deadly. I hated the summers that seemed to stretch from May 1st to the end of October, but the months of November and February are so extraordinary that heaven is the only description that is sufficient.

A few years after I arrived in Tucson I began to ride a bike to recover from knee surgery, and discovered that long rides in the Sonoran Desert were therapeutic both for the body and soul. In the 1990s Tucson was a very bike friendly community, and you could choose rides of any flavor; climb 6500 feet up Mt Lemmon along the Catalina Highway, ride the frontage road near I-10 to the north and easily average 22-25 miles an hour, group rides, and daily commutes. My first “serious” bike was an aluminum framed Cannondale, and in 1990 I purchased a sweet steel lugged Serotta Colorado. I entered a number of the centuries, and in 1991 I signed up for one of the premier long rides, the El Tour de Tucson.

The official poster for the 1991 El Tour de Tucson. The route was 109 miles and traversed the perimeter of the Tucson Valley.

The El Tour de Tucson, which had its inaugural event in 1983, is one of the nation’s largest single day cycling events. The father of the Tour, Richard DeBernardis, wanted an epic event that captured the challenge of “riding the perimeter” of a landmark, and circling the Tucson Basin fit the bill perfectly. In 1991 the event attracted around 3000 cyclists – which seemed immense to me when I pushed my bike to the start line at the Sheraton El Conquistador on the north side of Tucson. It was a cool Saturday morning just before Thanksgiving, and riders were segregated in “corrals” based on ability – I was in the massive public corral. It took me a little less than 5 hours and 20 minutes to ride the 109 mile course that included some iconic peculiarities of the El Tour (there were two “water” crossing that require the cyclists to dismount and carry or push their bikes – mostly the crossings are about getting off the bike, but sometimes they are wet!). Cyclists that finished the course in times between 5 and 6 hours received a “gold medal”, and I only regretted that I totally bonked the last hour and imagined I barely missed out on a “platinum” medal (it is really unlikely I could have made up the 20 minutes, but that is the power of positive thinking!). I rode the El Tour again in 1994 when the temperatures at the starting time were much less than 40 degrees and froze, but still did the ride in less than 5 1/2 hours.

Rainfall totals around Tucson for 8 hrs beginning at the start of the El Tour de Tucson on November 23, 2013 (figure made at Rainlog.org click on the image for a full size image to see the rainfall totals). The three day storm dumped nearly 3 inches on the Old Pueblo.

When I left Tucson in 2003 I always thought I would return to ride the El Tour often — I did not find the time until 10 years later when a couple of friends from Los Alamos and I entered the 31st version of the El Tour. We headed out from New Mexico on Friday, November 22, and by the time we got to Tucson it was raining. It is not unusual to get some precipitation in Tucson in November, but the storm forecast called for a significant chance of rain during the race.

It rained overnight before the race, and was lightly sprinkling at the start of the race. Cold and wet, I waited at the start line with high expectations — how bad could it be? Well, it rained nearly continuously for 4 hours. The map above shows the rainfall totals at stations across the Tucson Basin during the race – many recorded more than 1.5″ during the race. I never had a more miserable ride – between the rain fall, the spray from other riders, and road grim that comes with big storms, the ride was a major challenge! I did the first 75 miles on pace for a 5:50 finish, but cramped up and limped home in a time of 6 hr 21 minutes, and placed 521 out of 1626 riders (the race officials pulled a large number of riders off the course because the Sabino Creek crossing became too dangerous – and thus there was a much smaller finishing cadre than usual). After a few hours of recovery, my friends and I vowed to return and conquer the El Tour in 2014 and simply celebrate the most ridiculous and wet ride we just experienced.

Crossing Sabino Creek in the rain in 2013. The organizers closed this crossing about 40 minutes after I crossed over.

The 2014 El Tour de Tucson

The line up for the El Tour begins before sunrise and the sky has a faint red glow associated with the sunlight diffracting from beyond the horizon. 3200 cyclist mill around the starting line in Armory Park near the center of old Tucson just before 7 am start time for the 104 mile race/ride (the distance of the course changes from year to year depending on road construction). It is always clear that the cyclist come in all varieties — there are expensive bikes, mountain bikes, tiny people, large bodies, and some just strange sights like the fellow in a hot pink body suit. The Armory Park area dates from the the civil war when Union troops from California established a military camp here, and today it is the heart of one of the oldest Tucson neighborhoods. It is cool — 38 degrees — as the starting count down begins. I know I am pretty far back in the corral, right behind a group of riders that are wearing jerseys advertising bicycle accident lawyers (Hurt in a Biking Accident? Call xxxx). I am not sure if this is some sort of message from father fate, but I am reminded that I really have to be careful over the next 30 minutes. The countdown from 10 signals the start — and I don’t move for 3 minutes as the mass of cyclist in front of me slowly start up; it takes another 1 1/2 minutes until I pass the official start line. The mass of cyclists is amazing. Finally, I am rolling along and hugging the far left side trying to pass as many of the cyclist as possible within the first 5 minutes.

Starting line corral at 6:45 am. The official starting line is on the horizon of the photograph, and I am in a sea of some 3500 riders get ready for the 104 mile event. A total of about 8400 riders competed in an El Tour Event and 5122 crossed the finish line at Armory Park.

Tucson sits in a broad valley (with an average elevation of about 2600 ft above sea level) surrounded by tall mountains in all directions. To the east and north are the Rincon and Santa Catalina Mountains, to the west are the Tucson Mountains, and to the South are the Santa Rita Mountains. Despite the high mountains, the El Tour de Tucson is a relatively flat course – rolling hills, but less than 3000 feet elevation gain/loss for 104 miles. Of course, this is because of geology! It is a little hard to examine geology from a bike, especially during a fast moving century, but I have the advantage of knowing about the geology and that makes the ride much more interesting.

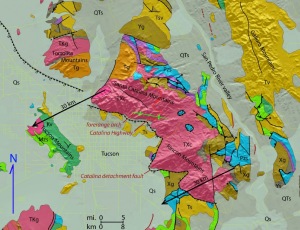

Simplified geology map of the area surrounding Tucson (from the Arizona Geological Survey). The red colors are granitic batholith rocks (although sheared). The Tucson Mountains, on the west side of the basin, were once located some 30 km to the east above the batholitic rocks. The Tucson Basin is an alluvial filled down-drop basin and range graben.

The Tucson Basin separates the crystalline cored mountains in the east (the Rincon and Santa Catalina mountains) from the mostly andesitic volcanics in the Tucson Mountains. Before about 1975 it was assumed that the Catalina-Rincon mountains were simply an uplifted batholith (granitic roots that represented large, mid-crustal depth magma chambers), but there was a perplexing rock fabric that was exposed with the granite that hinted at much more complex geologic pedigree. Around 1980, Peter Coney (an extraordinary geologist from the University of Arizona) proposed that this fabric was the result of extensive “stretching” of the crust and denuding of the deep seated rocks along low angle detachment faults. The fabric in the rock is a metamorphic (recrystallization due to extreme stains due to the crustal extension) overprint on the granites. The Catalina-Rincon mountains became the “type” locality of what geologist coined as metamorphic core complexes (MCC). When I was a young faculty member at the University of Arizona there was an intense debate on how low-angle detachment faults could form – in fact, to this day, their origin is hotly – and emotionally – contested. What makes the MMC model so significant for the Tucson Basin is that it provides an mechanism to connect the Tucson Mountains to the Catalina-Rincons; the Tucson Mountains once set on top of the Catalina Mountain rocks!

A model for the MMC based on the Catalina-Rincon Mountains (from a paper by Spencer and Reynolds, 1996). Around 30 million years ago the crust began an episode of extraordinary extension and the upper crust was transported to the west along a detachment fault. As this detachment fault “uncovered” deep seated rocks, these rocks uplifted creating a large domal structure, which is defined by the crest of the Catalina and Rincon mountains today. The rocks that were “pulled” to the west eventually traveled some 30-50 km.

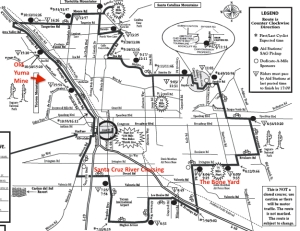

The start of the El Tour sends the riders for a short jaunt to the south before ending east and crossing the Santa Cruz River. The Santa Cruz River is a misnomer today – it is a dry ribbon of sand that only comes alive when there a large rainstorms that run off the parched desert landscape. The Santa Cruz River drainage basin covers a large area in southern Arizona, and eventually empties into the Gila River just south of Phoenix. Two major tributaries of the Santa Cruz — again, dry sandy washes most of the time – are also crossed by the El Tour. These are the Rillito River which drains the southern Catalina Mountains, and the Canada Del Oro which drains the northern Catalina Mountains. Last year all three washes were flowing with brown, churning water; this year they are sandy hiways.

The first 5 miles of the El Tour is all about survival – avoiding accidents and falling water bottles, getting ahead of wandering cyclists, and making a couple of sharp turns with cyclists of mixed experience. There is lots of shouts of “hold your line” – mostly in vain, but survive I did! After about 15 minutes the rider field is beginning to spread out, and the course turns back east; almost immediately we have our first “river crossing” — a run through the sandy Santa Cruz channel. The riders have to dismount and wade/walk/trot about 150 yards. This crossing seems crazy, but it actually spreads out the rider field.

Riders crossing the Santa Cruz — I am in there somewhere. Once you come up the east bank the riders are pretty spread out, and the real cycling begins. Photo from the Arizona Daily Star.

Once I climb out of the wash I quickly get back on my back on my bike knowing that the real ride begins now. The vistas to the east are spectacular (although, in truth, my glances towards the Rincons are very brief as I mostly worry about other cyclist’s wheels). The detachment faulting that beheaded the Catalina-Rincons occurred between 30 and 20 million years before the present. Around 10 million years ago Southern Arizona was subjected to another episode of crustal extension, characterized by fairly steeply dipping faults (in opposed to the shallow dipping detachment faults) and a whole series of down dropped grabens were developed to accommodate the extension. In the Tucson area a series of high angle faults down dropped the area west of the Catalina-Rincons producing a deep basin. Subsequent erosion of the mountains has filled the basin with sediment, and the relatively flat topography of the developed area of Tucson belies the 1000s of feet of sediments filling the basin. The fast flat track of the El Tour more or less follows a contour line circling the basin.

A notional model for the formation of the Tucson Basin and surrounding areas (from the Arizona Sonoran Desert Museum). Looking from the north to the the south, the sequence begins 30 million years before the present with the eruption of a large andesitic volcano.

The first hour of the bike ride is mostly uneventful; I averaged 21 miles per hour and pass at least a 1000 riders. The course loops around Tucson International Airport, and eventually turns along the frontage road of I-10. Finally, we turn north off the I-10 frontage road on to Kolb Road and cross over the massive freeway. A few minutes after the peddling along Kolb the riders pass through a unique Tucson landmark — the Bone Yard. Kolb road slices across property associated with Davis-Monthan Air Force Base that is home to the Air Force Materiel Command’s 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) – an organization charged with “dealing” with excess military and government aircraft. In reality, “dealing” with excess aircraft means miles and miles of out of service planes parked in the dry Tucson desert. As I cycled along Kolb I can see planes to the left of, planes to the right (and I am stuck in the middle with a bunch of jokers on bikes). One of my favorite planes in the line up are a few hundred B-52s that have their wings chopped off – all in the name of the START I treaty that required the US and Russians to remove a large number of delivery systems for nuclear weapons.

A 2014 google image of the Bone Yard. The vertical stripe is Kolb Road, the route of the EL Tour, and the line up of decommissioned aircraft stretches for miles.

At about mile 29 the already huge mass of riders merges with the riders that have chosen to ride the 75 mile tour. The merger is more than vaguely related to a stream being captured by a river; the 1200+ riders that are starting the 75 mile course flow in from the left, but are slower than the passing mass of the 104 mile cyclists, so they tend to form a strip of cyclists that keeps its “identity” for at least a half a mile. The organizers plan the start times of the shorter routes such that all but the elite riders can arrive at the finish line within about a 2 hour window. This means that although the long stream of riders gets thinned out by cycling ability and speed it gets repopulated 3 times (for the 75, 55 and 40 route starts) and you never are cycling alone – you get 8400 friends joining you!

A few miles after the merge of the 75 milers the course turns north on to Freeman Road, and begins a 3 mile climb up Freeman Hill, the high point along the El Tour. The climb is only a few hundred feet, but it serves to break up the pack into much smaller groups. Freeman Road is the western boundary of Saguaro National Park East, and home to one of the largest saguaro cactus forests. Saguaro are only native to Arizona and a very small region of California in the US (despite showing up in advertisements for salsa from Texas, Oklahoma, and even New Mexico — sigh), and are a remarkable sight. The cactus can grow to 70 feet in height, and typically live for more than 200 years. For the first 70 years or so of life, a saguaro is a solitary green thumb; after 70 years the cactus might grow arms, giving the saguaro an anthropomorphic silhouette. Riding along Freeman road my state of exhaustion causes me to image the saguaro are a marching army of green aliens.

Image circa 1935 of what will become Saguaro National Park East, right along the El Tour course. The cactus in the foreground about about 55 feet tall.

At mile 47 (and 2hr 21 minutes into the race for me) the El Tour arrives at the Sabino Creek crossing – an event in its self. Sabino Creek travels through Sabino Canyon which is a deep incision into the southern flank of the Catalina Mountains, and has its headwaters just below Mt. Lemmon, the high point in the mountain range. Sabino Creek is an ephemeral stream, but is usually flowing in the winter months due to the high mountain precipitation. The average stream flow at the Creek during the tour is usually on the order 10-50 cubic feet per second (a fire hose is about 1-2 cfs). During last years El Tour the flow reached a few thousand cfs, which meant that the water was calf deep when I waded through – this year the stream flow is more like a garden hose, channel through a culvert. I dismount to run along the dirt crossing and use the porta potty. There is a Mariachi Band playing, and scores of volunteers cheering the riders on and refilling rider’s water bottles. I pause and listen to the music and look at the dry stream boulders at the crossing – and they are fantastic. You can see large blocks of light colored granite as well as boulders of dark banded gneiss. The gneiss was created by the strains associated with the detachment faulting 30-20 million years ago; because I am dismounted from my bike I can actually see the geology!

Sabino Creek Crossing – dry in 2014, but still have to dismount. The Mariachi Band was great, and the volunteers here are fabulous.

Once we pass through the Sabino Creek aid station there is about 57 miles to go. The first stretch of the remaining route is through the Tucson Foothills – a mostly swank and newer group of neighborhoods and resorts located on the Santa Catalina Mountain alluvial fan. After about 60 miles the El Tour turns north on Oracle Road; this is where the change in Tucson since my arrival in 1983 becomes overwhelmingly apparent. In 1983 there were about 550,000 people in Pima County, mostly residing in the area around Tucson proper. There were essentially no homes along Oracle Road – even when I rode my first El Tour in 1991 this section of the course was largely rural mesquite chaparral. Today it is developed and most of this section of the course is through neighborhoods. By the time I left Tucson in 2003 the population of greater Tucson had grown to about 900,000 and today it is nudging 1.2 million. As typical of southwestern cities and communities this population growth translates to suburban sprawl; the population of Tucson proper has not grown much, but all the open desert around the Old Pueblo is vanishing. Given the scarcity of water this population push is unsustainable, but likely to continue. I suspect that when I return to ride the El Tour in 2026 – I will be 70 year old – the entire ride will be urban/suburban.

When I arrived in Tucson in 1983 the population of the greater Tucson area was a bit more than 550,000. By the time I left it was 880,000 and today it is just a little less than 1.2 million. Most of this population has settle on the fringes of Tucson in places like Oro Valley and Marana — when I rode the tour in 1991 there were no houses along the northern part of the route. Today it is becoming crowded.

Cycling along through the foothills and on to Oro Valley I am now in a group that will be with me until the finish. We work together — although we are rank amateurs everyone takes a pull, and we maintain a nice pace. I am pretty sure by mile 65 that I am going to easily finish under 6 hours. I feel very strong, and have been sticking to my fueling and drinking plan. What a difference a year makes! Last year in the rain this part of the course was littered with riders shivering with hypothermia at the aid stations, but today everyone seems like they are part of a schooled peloton.

The pace line coming down Tangerine Road. I found a group of about 7 that worked together for 20 miles,

After the quick descent from the Tortollita alluvial fan the El Tour course passes under I-10 and does a hard left on to the frontage road along the bank of the Santa Cruz River. The course is a relatively straight 22 mile shot back to down town Tucson, and a steady, gentle climb. However, I am tired, and know that this is slog time. It should take me about 1hr and 15 minutes. The real reason it is a slog is is not the gentle uphill but that there is a pretty strong head wind. However, I am with the same group of riders, and we continue to work together (although slower, as our average pace is more like 17 miles per hour compared to 20 miles per hour earlier in the race).

10 miles into the homeward stretch the El tour crosses over a road named El Camino Del Cerro. If I turned right here I would reach the home I built in the Tucson Mountains. I was single during the construction and lived in basic camping conditions for the year 1986. The house was definitely on the outskirts of Tucson at the time (not so much today!), and was located only a short mile from one of the most famous Arizona mineral localities, the Old Yuma Mine. As I noted earlier, the Tucson Mountains are a volcanic complex that once was located above the Santa Catalina Mountains. That old volcanic complex was moderately mineralized, and the transport along the detachment fault left the mineral riches intact. There are four mines of significance in the Tucson Mountains, and the Old Yuma was the largest and most successful. The Old Yuma was mined for gold, but it also was rich in colorful secondary lead minerals. It was a favorite locality for collectors that occasionally found seams covered with deep read vanadinite or yellow wulfenite; these specimens now grace mineral collections world wide. I visited the Old Yuma many times, but never found anything of note. After I left Tucson the Federal government purchased the mine from my friend Richard Bideaux and cemented the shafts and removed all the mine dumps — it is a locality no more.

Finishing the 32nd El Tour de Tucson

5 miles from the finish any pretense of working together with my group falls apart. Everyone can taste the finish line, and we are at a time of just under 5 hours. I am peddling comfortably, trying to save a little reservoir for the last mile which can be a sprint. I round the corner to the last mile before the finish line, and stand to sprint. However, I seem to have encountered some sort of gravitational well and my bike simply stands still! I beg my wheels to turn faster, but they don’t. I cross the line at a clock time of 5 hrs 24 minutes and 20 seconds; the chip time, which takes in account that I did not even reach the start time for over 4 minutes, is 5 hrs, 18 minutes, 56 seconds (this is my garmin time!). I average 19.5 miles per hour, and am pretty happy for an old guy. The deluge of 2013 suddenly becomes a fond memory! Michelle, my wife, entered her very first cycling race in this El Tour, riding the 55 mile version of the course. She finishes in under 3 hrs, and looks fresh like she could have done the 104 miles event. The furthest that she ever has cycled before the El Tour was 42 miles, so her’s was a fantastic ride. All told, about 8400 riders participated in El Tour de Tucson — covering difference distances, but all ending together at Armory Park. The finish line park is a festival, and unlike the finish line of an ultra run, every body type in the human race is represented — and everyone is smiling.

The 2014 El Tour did not turn out as well for some of my other Los Alamos companions because of tire troubles, but over all, we all feel the disappointment of 2013 vanquished. I don’t know for sure when I will be back, but the event is one of those “great challenges” that one just needs to experience. Besides, expending 5500 calories in a race means you are free to indulge in one of Tucson’s iconic restaurants, El Charro and feast on the world’s best carne seca. Who says bikes, geology and chile don’t mix?

Nice race report, Terry! Strange about the sprawl and sad to hear about the corking up of the Old Yuma Mine. I was fascinated to hear about the bone yard and look forward to pedaling through it myself. Next year. If I’m reading you correctly, you rode this one nearly as fast as you rode the one in 1983? If so, awesome! Not bad for “an old guy.”

Jim — thanks so much for making my bike sing! Truth be told, my first El Tour in 1991 was 109 miles, so even though my time 23 years later is about the same, the older course was longer. But I enjoyed this year more than 1991!