“Though the road’s been rocky it sure feels good to me” – Robert “Bob” Nesta Marley, Jamaican musician, poet and philosopher.

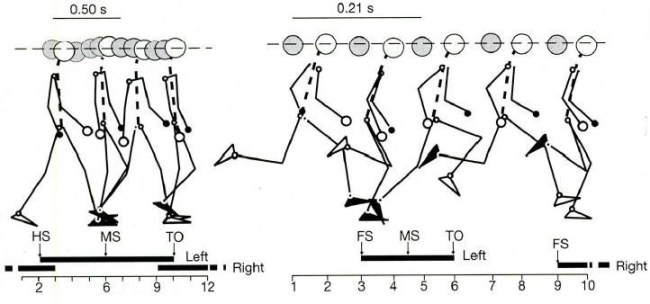

Running downhill at the end of the Mt Taylor Ultra. Running in the mountains is a special kind of freedom. It is not the running, nor just the mountains, but the marriage of the two. The bow legged stride I exhibited in this run is a sure sign of knee damage.

In the fall of 1971 I decided I would run to high school from my home three days a week. The decision was driven not by any love of running, but rather my desire to get into outstanding shape and prepare me to make the cut for the JV basketball team at Los Alamos High School. In those days, I lived about 10 miles from school and the run had a gain in elevation of about 1000’; the run was along a road with a wide shoulder, and I could leave in the dark and make up “the hill” before school started. This well thought out plan to overcome my lack of athletic ability (and complete inability to jump even a few inches off the ground) by having superhuman endurance crashed back into the boneyard of reality after about 3 weeks. My knees became inflamed, and I hobbled around the basketball court under the disapproving gaze of the coaches that wondered why I did not just stick to the chess club (which I was a member of, by the way). My mother took me to the family physician, who in turn, sent me to a specialist. I was diagnosed with Osgood–Schlatter disease (OSD) – inflammation of patellar ligament just below the knee cap. OSD is relatively common in adolescents, especially boys, who are undergoing growth spurts. The pain was intense in the quiet dark hours of the middle of the night, and I became well acquainted with ice packs and the bright red color of skin that feels frozen from the cold. 50 years ago, the treatment regime was “rest” and waiting out the growth spurt. Eventually I could run again, although I never quite gained the super endurance that would allow me to overcome my lack of coordination.

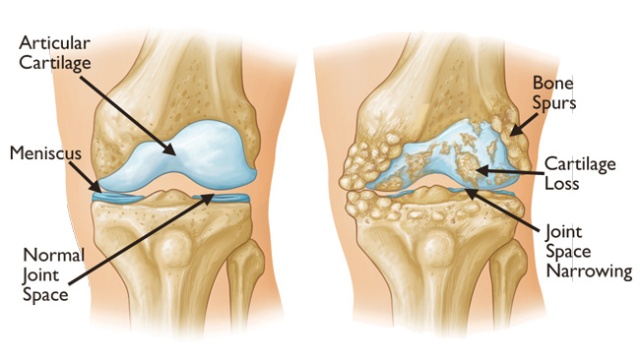

Today it is known that people that have suffered through OSD are much more likely to develop arthritis, or inflammation of the leg joints – knees and hips – in later life. Arthritis is really a description of symptoms, and there are dozens of “types” of arthritis. I am cursed with osteoarthritis, which causes the cartilage to breakdown over time. For a lucky few (including me), the breakdown of cartilage is accompanied by the growth of bone spurs, especially on sides and beneath the knee cap. These tiny osteophytes are like small thorns on a rose bush – rub them in the wrong way and they cause pain. Realistically, my osteoarthritis is likely the result of heredity. However, I loved playing basketball, and to a lesser extent football, and this combination of osteoarthritis and sports that impacts joints conspired to make me a punch card for surgeries: I have had enough that surely I qualify for a TV advertisement for Stryker, one of the world’s larger manufactures of prosthetics.

A fews days post surgery in 1989. My son has sympathetic knee pain, and is propping his knee up to relieve the misery. 2nd knee surgery, and the cartilage was 60 percent gone.

On April 25, 2017 I became a full bionic man – well as far as my legs are concerned. But the journey to having more metal in my body than is present in most modern automobile bodies began in 1976 I when I was playing in a basketball game. My left knee got twisted and I had my first surgery to remove a tear in the cartilage. I recovered; in 1989 I repeated the experience, but on my right knee. I went into surgery to remove the tear, but once the surgeon looked at the knee he discovered that lack of cartilage had caused scoring of the bone, and decided to refinish, or smooth the bone. That was a crummy experience, and caused me to have to delay my honeymoon (which had already been delayed for more than a year due to other reasons) – but I was told on no uncertain terms that I could never run again. I followed that direction for an entire year, and then I was back to playing basketball 5 to 7 days a week. But, as an insurance policy I took up bicycle riding in a serious fashion and started riding centuries, my introduction to endurance sports. It turns out I bought the wrong kind of insurance policy, and I had to have my left hip replaced in 1998 at the tender age of 42. I never played basketball again.

X-Ray of my right knee, after my 2009 replacement. The grinding joint is replaced with a smooth surface. The knee cap has be reshaped and all the bone spurs removed.

Eventually, even though I no longer played basketball, I had to have my right knee replaced in 2009. The refinish job I had gotten 20 years earlier had extended the lifetime of my knee remarkably, but bone-on-bone eventually won out. The recovery from knee replacement was difficult and humbling; but the result was transcendental. Within a year I was climbing mountains with ease where I had struggled before. Magic. In 2012, I started to run trails, and found a true joy. I knew that there was advice not to run again with a prosthetic, but I also understood the research on the wear and failure was very conflicting (I wrote about running with artificial joints: https://wallaceterrycjr.com/2014/04/29/conventional-wisdom-and-scientific-fact-the-dilemma-for-a-trail-runner/ ). Frankly, I was far more concerned about my natural knee, as I knew it was the evil twin of my knee that had alreay been replaced. In 2013-2015 I ran between 2200 and 2500 miles per year. Check ups of my artificial joints showed no ill effects – but I knew that my left knee was slowly grinding to pulp. I could see my knee cap “growing”, and I was having trouble bending my knee enough to walk up or down steep stairs.

A view down Bat Canyon from the turn around point of the Canyon de Chelly 55 km ultra. the race climbs and then descends about 1000′ over a rocky trail.

A Fateful Run

In October of 2015 I ran a fantastic 55 km ultra through the scared lands of Canyon de Chelly. The race is a 17 mile out-and-back through a sandy wash; mile 15.5-17 is a steep climb of 1000 feet out of the canyon to the rim (https://wallaceterrycjr.com/2015/10/12/sacred-land-a-run-through-canyon-de-chelly/ ). After refueling at the turn-around, the course is a dive back into the canyon; steep and rocky. Within a hundred yards I knew that something was wrong. My left knee was swollen, and would not bend – so my decent was less a run and more of a hop, stumble, hop. The first 17 miles took me 3 hrs and 12 minutes; the reciprocal took me almost 5 hours. After the race I iced the knee, but 12 hours later it was still stiff and unresponsive. I knew that this a clarion signal that “the time had come”. However, within a week I could run again, and against all rational judgements I began to believe I could “will” my knee to last a few more years. In cognitive sciences this is called Unrealistic Optimism or Optimism Bias, which is defined as “cognitive states that are unrealistically optimistic are belief states, whether they are false, and whether they are epistemically irrational.” Most people that have the so called type A personality can relate – it is the illusion of control, an exaggerated belief in one’s capacity to control independent, external events. There are lots of benefits to unrealistic optimism – many people call this “extreme will power” – but it rarely results in miracles.

The last race…the Santa Fe Ultra with Dave Zerkle and Dave Dogruel escorting me through 34 miles of up and down, only to finish DFL.

I continued running ultras for the 10 months after Canyon de Chelly. In fact, I ran 5 races of 50 km or greater, and logged some 2,100 miles in training. But the expiration date had passed on my left knee (I assign the expiration date to the Canyon de Chelly ultra), and my run began to more resemble a hobbled wobble than a graceful galloping gait. My last race was inaugural Ultra Santa Fe race in the Sangre de Cristo mountains above Santa Fe. The race is a circuit from the top of the ridge line at 12,000′ to the juniper covered arroyos at 7,200′ along the eastern margin of the Rio Grande Valley (https://wallaceterrycjr.com/2016/09/20/the-santa-fe-ultra-lost-climbs-friends/?iframe=true&theme_preview=true ). This is a tough and beautiful event – I really like this race – but for me it was truly the end. I finished the race DFL, and was incredibly fortunate to be escorted by my friends and faithful running companions Dave Zerkle and Dave Doggrel. The will was there, but the way was not. The day after the race I began to plan my next journey; one final knee replacement, recovery, and then completing the Noles 14 14ers course in 2019 (I am not stupid – I never thought about doing this ridiculous trek in 60 hours; I am shooting for 120 hours!).

A cartoon depicting the deterioration of a knee due to osteoarthritis. The loss of cartilage causes the knee to compensate, and often the victim begins to develop a bowleg stance. The knee also loses its ability to lock.

Knee Surgery Stinks!

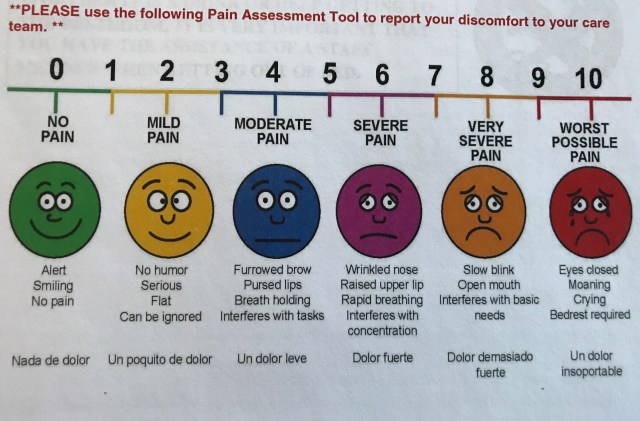

I am not particularly special in having a full knee replacement. Nearly 700,000 people have a partial or full knee replacement annually in the US. Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease in adults, and its incidence increases with age. However, the expression of joint damage is usual minor for the vast majority of the population – only about 8% of the American population develops serious damage, and 75% of those are older than age 60. My superpower is that I can have been able to destroy cartilage from a very young age. When my hip was replaced in 1998 the surgeon told me I have the strange combination of a hip joint of an 80 year old, and the bones of a 25 year old; the cartilage was gone, but the bone was extremely healthy as measured by density and strength. I have been struggling joint issues for at least 30 years – and likely this struggle was associated with pain (I say likely because I have a hard time with identifying joint pain). A recent study in the journal Pain (yes, there is a medical journal with the eponymous tag for something we all experience) looked at the human ability to manage long term pain (Brown et al, 2015). “The experience of pain in humans is modulated by endogenous opioids, but it is largely unknown how the opioid system adapts to chronic pain states….however, our study is consistent with the view that chronic pain may upregulate OpR availability to dampen pain”. Although the language is particularly opaque, the summary of the study is that for arthritis sufferers the body adapts to the pain. This seems pretty logical – but it also one of the greatest sources of frustration when one approaches surgery. Over and over the question the physician, x-ray tech, physician assistant, etc (including the hospital billing agent!) asks is “please quantify the level of pain you are experiencing in your knee. They ask you to use the chart below as a guide so you can give the pain level with a numerical value.

This is the famous “pain chart”. Please quantify your level of pain, and just in case you are having trouble use a mirror and look at your facial expression.

I usually answer “I don’t really have much pain, I just can’t really walk”. This leads to an downward spiral of a conversation: “Well, if you don’t have pain then we really should not perform surgery”….”But I can’t walk”….”So, is it painful to walk, and how painful”…”Nothing is as painful as this conversation, just frick’in understand I can’t walk anymore”….”I will record that you have a high level of pain”…”Thank you, and I do believe that I presently have a pain in my butt, level 8 (see the slowly blinking eyes and open mouth in the chart above)”.

Despite this loopy dance about joint pain, make no mistake, once you start down the path to knee replacement it is all about pain. The damaged joint is painful even if you have adapted to the pain – it effects not only the way you walk and sit, but the way you sleep and stand. The ultimate goal is relieve that pain, but the joint replacement is a violent invasion on the knee, and the new pain, although ephemeral, is hardly trivial.

Comparison of my left knee pre-surgery, and the knee of a “normal” male, 36 years old. My knee, on the right, has bone on bone contact, bone dissolution due to knee-cap aggravation, and a wide gap on the left side due to long term adaptation to the irritation. The wide gap is common, and causes the development of a bow legged gait.

The goal of a full knee replacement is to remove damaged bone and replace it with new materials that allow the knee a full range of smooth motion. The picture above shows my left knee pre-operation; The femur and tibia are touching on the left side and all the cartilage is gone. That constant contact has caused a gap in the bones on the right side – this is one of the body’s adaption mechanism to the pain. Unfortunately, it also changes the biomechanics of leg motion, and caused my leg to become “bow legged”. Finally, the constant contact of the patella on the knee sans cartilage has prompted some bone dissolution giving the knee an a appearance of limestone fossil. Several figures above this text is the x-ray of my replaced right knee; the damaged areas have been cut away and replaced with metal and flexible cushion constructed of polyethylene.

The reason knee surgery stinks is the processes involved in placing the prosthetic into the knee – to relieve pain, one must cause pain. However, I am reminded of words of Benjamin Franklin: There are no gains without pains. After months of planning, I arrive at the hospital to be checked in for surgery. Although I have been through this several times before, it is impossible not to be anxious. Plus, I am a paranoid worrier – I have spent the last two weeks planning for every disaster. I visited the grandkids, I told my wife what to do with my mineral collection, I cleaned up my office…. Anyway, checkin and finally getting ready for surgery is just the start.

Modern knee replacement is miraculous. The first process is deadening the legs, and that is done with a spinal block, the injection of anesthesia into the fluid surrounding the spinal cord in the lower part of my back. Within about 5 minutes my feet feel hot, and then numb. The numbness rolls up both legs, and within 15 minutes there is absolutely no feeling below the waste. It is a bit freaky in that there is complete control and feeling from the belly bottom up, but nothing at all below. Shortly after the anesthesia takes hold I am wheeled into the operating room. Next to the operating table are several small saws – a frightening sight! However, the staff give me a mild gas and I am fast asleep. Next thing I know I am waking up 2 hours later in a recovery room. I missed all the action! My surgeon sliced my leg open along an 8″ line from slightly above the knee to below. This slice cut through the quadricep tendon and allowed access to the knee cap. Once the cut is made, my surgeon bends my knee 90 degrees to have access to the bone. He then uses the saws to remove the bottom of the femur and the top of the tibia. Another saw is used to reshape the bones to fit the parts of the artificial joint. The new parts have pegs that are pressed into the bone, and will be eventually inter-grown with the new growth of the bone. Then my surgeon focused on reshaping my knee cap – removing the spurs and rough spots. After all this stuff is done the knee is straightened and the muscle is stitched up, and finally staples are applied to pull the wound together.

Four hours after surgery. A new knee! blood drain means the bone marrow is still working. My smile is due to the drugs.

There is no pain for several hours – until the spinal block begins to wear off. Then all that violence to the bones screams. There is a long tube in my knee that drains the excess blood. Since the bones were cut, and the prothesis was pressed in, blood continues to ooze out of the joint for 24 hours – in my case it was nearly a quart. Nothing feels good 12 hours after surgery is done. However, the journey to walking, hiking and running has begun!

My first steps – not exactly freedom, but way better than bed rest!

First Steps: 18 months of recovery

The day after surgery the recovery begins. With knee surgery there are so many nerves and muscles cut you have to learn to walk again. Heel down, rolling to the toe – it seems natural, but I have to think about every step. The leg that was operated on is weak, stiff and sore. Walking 100 feet is a chore – but also a delight. Pushing a walker up and down the hospital hallway is a bit surreal. But the walker is my friend for 6 weeks. Crutches don’t teach you to walk; the prothesis corrected my bowleggedness, the goal now is to be able to “lock” the knee. It has been 10 years or more since I could lock the knee – as the arthritis progress that knee slowly buckles (lay flat on a bed – the back of a normal knee rests on the mattress, but an arthritic knee like mine with have a gap of several cm).

I know that the process of relearning to walk, making the knee functional, and strengthening the leg will take 18 months. There is no way to shorten the recovery. Past experience tells me that the first 6 weeks seems like an eternity and progress is frustratingly slow. But the day the knee locks, then I will know that I am on the cusp of full functionality. Locked and Loaded. See you on the trail in 2019!