God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand tempests and floods. But he cannot save them from fools ― John Muir

Smoke plume billowing above Pajarito Ski Hill (Tuesday evening, June 4; Steve Black photo)

On Friday (May 31) a downed power line started a wildfire in the west-central region of the Jemez Mountains near a deep drainage called Sulfur Creek on the western margin of Redondo Peak. The fire burned uphill on the eastern side of the drainage rapidly, and was named the Thompson Ridge Fire (although not on Thompson Ridge). The sight of smoke in the Jemez was visible in Los Alamos by 5 pm and the entire town held their breath, thinking “here we go again”. By Saturday afternoon smoke from the plume began to collapse on Los Alamos, and the smell of burnt pine caused an even stronger visceral reaction triggering memories from June 2011 when the Las Conchas Fire swept around the town, led to a week-long evacuation, and charred more than 150,000 acres. The question on many peoples’ minds is “why?” It certainly seems that the entire Jemez is going to be soon burned, leaving a high elevation desert. The 1996 Dome fire, the 2000 Cerro Grande and the 2011 Las Conchas Fires have changed the scenic vista of the eastern Jemez profoundly and probably for hundreds of years. Each of these fire was bigger than the last: The Dome fire was 16,500 acres, Cerro Grande was 48,000 acres, and Las Conchas was over 150,000 acres. The obvious question is “are the fires getting bigger and more frequent?”

The Jemez Mountains are a unique alpine island created by the Jemez Volcanic Complex (JVC) that was active for about 800,000 years beginning around 1.4 million years before the present. The JVC lies along a line of volcanoes that arcs across New Mexico from the southwest to the northeast, known as the Jemez Lineament. In the southwest the San Carlos Volcanic Field (in Arizona) anchors the Lineament, and it passes through Mt Taylor near Grants, the Jemez, and finally terminates in the Raton Volcanic Field. There is no real good explanation for the Jemez Lineament, and geologists continue to debate both its cause and significance. The JVC is the largest of the volcanic fields on the Lineament. The geologic map above shows the Jemez Mountains. The Jemez Mountains surround the Valles formed during the collapse of the JVC about 1.1 million years ago. In the middle of the collapse crater a great “resurgent dome” was pushed up by the death throes of a great volcano. This dome is Redondo Peak – which is not an eruptive volcanic cone, but an extruded dome. Redondo Peak is the high point in the Jemez at 11,258 ft elevation. The uniqueness of the Jemez was recognized by the first geologic expeditions of the west; John Wesley Powell himself visited the Jemez in the 1880s and described it as a giant volcanic field (anyone interested in the geology of the Jemez should read Fraser Goff’s book “Valles Caldera: A Geologic History”).

The volcanic field and Redondo rise above the surrounding New Mexico highlands to form a roughly circular mountain range. This range has its own flora and fauna – or at least it did before the great fires of the last 25 years. Elevations above about 7200 feet were dominated by ponderosa pine and various fir and spruce. After a fire the pine is replaced by scrub oak and lower growing vegetation. Craig Allen has studied the fire history and vegetation of the Jemez, and has found dramatic change.

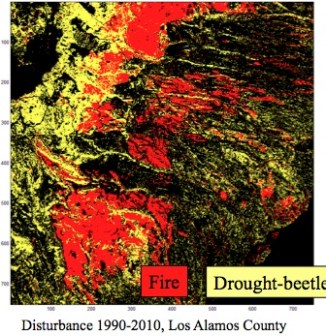

This change is from both fire and mortality of the pine forest due to prolonged beetle attacks. The figure above shows a color-coded map of the Pajarito Plateau, centered on Los Alamos, and where fire or beetles have affected our forests. In twenty years 90% of the forest have been subject to stress.

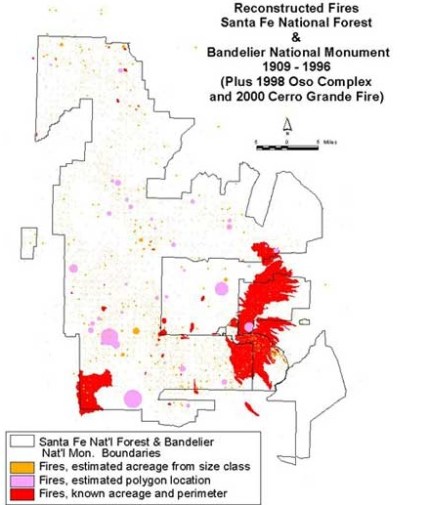

The question of “why” is the Jemez burning can be partially answered by looking at the fire history of the mountains. There are various ways to do this, including coring trees looking for scars from ancient fires, and looking at the peats in the meadows within the Valles and looking for preserved ash and charcoal layers. When Allen and other researchers did this they reconstructed a fire record that stretches back nearly 10,000 years. There are literally tens of thousands of fires over this period, and some strong trends are worth noting in the last couple of hundred years.

The figure above shows the location of nearly 5000 fires in the 20th century, along with the Cerro Grande Fire. The great bulk are small, local wildfires, probably almost always caused by lightning. There is evidence in the distant past of very large fires – probably as large as Las Conchas – all across the Jemez. There is a moderate correlation with those large fires and large-scale drought. However, before the mid-20th century wildfire was most commonly characterized by small, frequent fires.

Beginning in the late part of the 19th century man began to have a significant impact on the ecology of the Jemez. Livestock grazing in the Jemez became “big business” and the removal of the understory grasses probably suppressed wildfire. The cows and sheep ate the grasses that supported spreading the fires.

In the 1930s the Jemez became a lumber supplier, and the region began to be heavily logged. This is particularly true for Redondo Peak and the Valles Caldera which were in private hands, and were not subject to the regulation of the Forest Service. The picture above shows a logging road from the mid-1930 on the northwestern side of Redondo. Today, logging roads are still seen across the Jemez, especially as spirals up the various domes. The lumber “boom” ended, and the forests began to fill in. Livestock grazing dropped dramatically, and new Federal oversight of wildfire suppression caused the forest cover to densify. By the 1960s the forests were much more dense then 200 years previous. The pathways for fire were increasing.

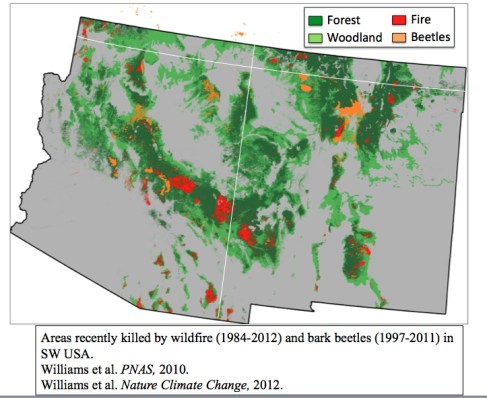

Over the last 2000 years there have been periods of drought and high precipitation. Around 1990 we entered a period of drought, and the window between 2000-2010 was likely the driest decade in a millennium. This drought stressed the trees, and they became much more susceptible to disease. In particular, the pine bark beetle attacked, and will eventually kill, more than 1.3 million acres of ponderosa pine in New Mexico and Northern Arizona in the period of 2002-04. The beetle problem is complex – stressed trees are one issue, but also the density of the forest allows the beetles to spread much more rapidly than in the past.

Nate McDowell and colleagues at Los Alamos produced the figure above that shows the loss of forest due to the beetles and fire. It is fair to say we are in a long-term, profound, change of our forest. The Jemez is not unique, but it does seem to be at the confluence of disease, drought, forest “management” and finally, the encroachment of man. Before 1950 the vast majority of wildfire was caused by lightning. However, since 1990 more than 85% of fires have a man-made fingerprint. For the four major Jemez fires in the last 25 years it is all man-made; The dome fire was caused by a camp fire, the Cerro Grande started as a controlled burn (what a total fiasco – and to this day an unpunished event), Las Conchas was started by a downed power line as was the present Thompson Ridge.

Although it is dangerous to predict the fate of nature, it certainly seems that large fires are going to continue in the Jemez for years to come. A break in the drought would help, but a short break would only promote the understory growth which would become the match stick once drought resumed. We are standing on the cusp of a major change for our beloved Jemez, and can only hope that luck and nature conspire!