Each volcano is an independent machine—nay, each vent and monticule is for the time being engaged in its own peculiar business, cooking as it were its special dish, which in due time is to be separately served – Clarence Dutton, American Pioneering Geologist, 1880.

Mt. Rainier, the great white mountain (for me, the great white whale!). This photo was taken on Sept. 9, as I flew into Seattle to begin my journey to the summit. The photo is from the east/north, and you can see the summit crater on the top left flank of the mountain. The clouds are at about 6500 feet elevation.

Mt. Rainier is the most iconic mountain in the contiguous United States. Its nearly perfect conic shape rising 14,410 feet above sea level, and located only 35 miles from Tacoma and Puget Sound make it the most prominent geologic structure in the country; the white cap of the summit plays a game of hide-and-seek with the major metropolitan sprawl of Seattle-Tacoma and when the clouds rise even the most jaded Emerald City resident is jarred by its majesty. I have long wanted to climb Rainier, but never found the opportunity in my youth or the time in my middle age. However, my wife surprised me with a gift on our 25th anniversary in 2013 – the opportunity to climb the great white whale. Work commitments still made the scheduling of the climb non-trivial, but finally in September of 2014 I had the chance to join an organized expedition.

Mt Rainier from an airplane flight (SEA-DFW) I took in the summer of 2013. The clouds cover the summit, which has a topographic prominence of over 13,200 ft. There are 26 alpine glaciers on Rainier which gives it its perennial white appearance.

Rainier has a special place in the minds of geologists – it is a magnificant monument to the violence of plate tectonics. The Cascade Mountain Range stretches from Mt Garibaldi located just north of the Canadian-American border to the Lassen Peak in northern California. Along the 700 mile arc of the Cascade Mountains there are at least 20 young volcanic peaks – Rainier is the highest today, although the nature of stratovolcanoes is that Rainier will eventually follow the example of Mt. St. Helens and “blow its top”. In the 1960s it was recognized that the Cascades where the volcanic signature of a subduction zone – the collision between the Juan de Fuca oceanic plate to the west and the North American continental plate to the east. I was a graduate student at Caltech in the late 1970s, and understanding the nature of subduction was a subject of intense research. In addition to stratovolcanoes, subduction zones are the source of most of the largest earthquakes observed on the planet. Understanding why some subduction zones had mega earthquakes – events with magnitudes that exceed 9.0 – while others only had earthquakes with a maximum magnitude of 8 or 7 was a mystery. In the Seismolab at Caltech there was a daily coffee in which the faculty and other graduate students discussed the most recent seismicity and new areas of research. It was in these “coffees” that a generation of seismologists were created – everyone was expected to contribute to the discussion and debate, and very foundations of modern seismology were laid. Hiroo Kanamori, perhaps the greatest observational seismologist in history, was pondering the “why some subduction zones have mega earthquakes” question and working with several of my peers developed the rationale for mega thrusts based on the concept of “coupling” between the subducting plates. This spawned the concept of “comparative subductology” which is rooted in Scottish geologist James Hutton’s concept of uniformatarism – if it is happening now, then it happened in the past, and will happen in the future. One of the surprises of the comparisons of subduction zones world-wide was that Cascadia looked a lot like the segments of the Chilean and Aleutian subduction zones that generated mega earthquakes in 1960 and 1964. However, Cascadian was pretty quiet seismically, so there was a general skepticism in the geologic community that Seattle would some day have an earthquake that would dwarf anything that could happen in California. Today the discussion is not about size of a future earthquake in Cascadia, but rather when and how often.

Caltech 1980 — I am one of the leaders of a field trip to Owens Valley (I am the guy at the far left with the clip board and the really strange ball cap) after the Mammoth Lakes earthquake sequence. The earthquakes occurred within a week of the eruption of Mt. St. Helens, leading many to suggest a link. The Seismolab was home to an amazing cadre of faculty and graduate students in the 70s and 80s that help define the paradigm of modern plate tectonics — including the understanding of the Cascadia subduction zone.

My own research at Caltech was more focused on computational methods for seismology and understanding the seismograms from nuclear explosions – however, I was captivated by the discussions of mega-thrusts. In May 1980 Mt St. Helens erupted – and the reality of the restlessness of Cascadia hit home. I very much wanted to climb Mt. Rainier right then. However, it took nearly 35 years before the opportunity would arise. Of course, this is a geologic blink (or wink!) of an eye, and the decades had not diminished my enthusiasm to walk on the volcano.

Google Earth image of the Cascades. The white dot in the middle is Mt. Rainier. To the south (to the left in the image) are Mt. Adams and Mt. Hood. This line of high peaks are stratovolcanoes above the subducting Juan de Fuca oceanic plate. The high mountains of the Cascades blocks the oceanic moisture and makes the Pacific Northwest coastal region a rain forest — and a relatively dry desert in eastern Washington and Oregon.

A brief history of Mt. Rainier (apologies to Stephan Hawking)

Most discussions that start with the topic of “history of Mt. Rainier” focus on it relatively modest relationship between the mountain and man. The earliest evidence of human occupation of the Pacific Northwest is about 13,000 years before the present, and it is certain that the mystic vision of the rugged, glacier -covered tower of andesite evoked the same since of wonder that it does today.

The first written records associated with Mt. Rainier are from the annals of Captain George Vancouver who was the commander of the English vessel Discovery that was sent to explore the Pacific Northwest. In May of 1792 the Discovery sailed into Puget Sound, and Vancouver saw the snow covered volcanoes of the Cascades, and noted three (Mt. Baker, Hood and Rainier) stood out “Like giants stand To sentinel enchanted land”. On May 8, Vancouver wrote “the round snowy mountain, now forming its southern extremity, and which, after my friend Rear Admiral Rainier, I distinguished by the name of Mount Rainier”.

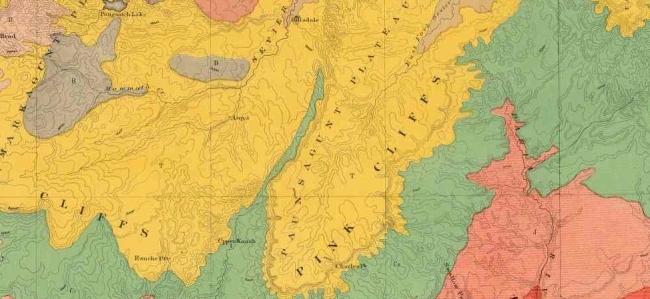

The eruptive history of the Cascade volcanoes (figure from the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network) over the last 4000 years. Mt. Rainier is the largest of volcanoes, but it the last few thousand years it has been less active than Mt. St. Helens.

The eruption history of the Cascades – about 50 eruptions in the last millennium – doubtlessly meant that the indigenous peoples knew that the Cascade peaks were volcanoes. However, this first recorded suggestion that Rainier was volcanic was noted in the diary of William Fraser Tolmie in 1833. Tolmie was a remarkable naturalist from Scotland that was trained as a physician at Glasgow University, and joined the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1832. Upon arrive in Puget Sound one of the first tasks he undertook was to visit Rainier on a “botanizing excursion”. In is notes he wrote that the rocks of Rainier were “volcanic”. I don’t know what character of the rocks lead him to that conclusion, but Tolmie set the stage for USGS studies 40 years later that would confirm that Rainier was a composite volcano. As a side note, Dr. Tolmie as also the first person to write about an earthquake in Cascadia when a small tremor struck Puget Sound on June 29, 1833.

Mt. Rainier attracted many attempts to scale its heights, but the first documented successful ascent occurred by the son of the first governor of the Washington Territory and a pioneering mountaineer in 1870. General Hazard Stevens (a well-named military man, especially climbing Mt. Rainier) first came to the Puget Sound area with his father in 1854 and resolved to climb the “great white mountain”. After a military career and the end of the Civil War, Stevens returned to Washington Territory, and teamed with Philemon Beecher Van Trump in August 1870 to climb Rainier. Stevens wrote an account of their journey – which was quite harrowing – that was published in Atlantic Monthly in 1876. Stevens wrote “We had spent eleven hours of unremitted toil in making the ascent, and, thoroughly fatigued, and chilled by the cold, bitter gale, we saw ourselves obliged to pass the night on the summit without shelter or food, except our meagre lunch. It would have been impossible to descend the mountain before nightfall, and sure destruction to attempt it in darkness… Climbing over a rocky ridge which crowns the summit, we found ourselves within a circular crater two hundred yards in diameter, filled with a solid bed of snow, and inclosed with a rim of rocks projecting above the snow all around. As we were crossing the crater on the snow, Van Trump detected the odor of sulphur, and the next instant numerous jets of steam and smoke were observed issuing from the crevices of the rocks which formed the rim on the northern side. Never was a discovery more welcome!” Today we recognize that they had found fumarole activity, a reminder that silhouette of Rainier is only temporary.

The Muir party summiting Mt. Rainier in 1888.

P.B. Van Trump would visit the summit 5 more times including guiding John Muir in 1888. Muir had to be convinced to undertake the climb, but once at the top he stated “I hardly know whether I had better try to describe the view but will say that for the first time I could see that the world was round, and I was up on a very high place. The air was very light…I stood there all alone, everything below and all so grand. I had never before had such a feeling of littleness as when I stood there and I would have stood there drinking in that grand sight, but they wanted to go so we started down”.

By the 1930s geologists had begun to unravel the complex volcanic history of Mt. Rainier. The present conically shaped mountain is quite young – less than 600,000 years old. Beneath the high reaches of the mountain though are a complex series of mostly volcanic rocks that record ancient geologic environment and long extinct versions of Mt. Rainier. The most prominent basement rock is the granodiorite of the Tatoosh Pluton (there are a range of ages for the pluton which probably reflects a complex history – it cooled between 25 and 12 million years before present) which was the crustal magma chamber of former stratovolcanoes.

A geologic cross-section through Mt. Rainier from Crandall (1969). The modern andesite and mudflows that define Rainier today lie above a large granodiorite batholith that is approximately 25 million years old.

Mt. Rainier birth as a stratovolcano probably occurred about 850,000 years before the present, and the bulk of the present conical shape is about a half of a million years old. The present summit has two craters that reflect recent eruptions. It is clear that in the past the summit of Rainier was somewhat higher — maybe reaching 16,000 feet elevation — but explosive eruptions have removed the older cap rock.

Although the nature of the Cascades and Mt Rainier were understood by the 1960s, it took the articulation of theory of plate tectonics to set the framework for why the stratovolcanoes exist. The North American plate, dominated by a large continental mass has interacted with an adjacent oceanic plate, known as the Farallon Plate, since Jurassic time (more than 150 million years before the present). Eventually most of the Farallon plate was subducted beneath North America, but a fragment remains off the coast of Washington, Oregon and northern most California. This fragment is known as the Juan de Fuca plate, and is being subducted at a rate of about 4 cm/yr. In addition that subducted oceanic crust is young – about 10 million years old. The USGS figure below shows a notional cross section beneath Washington.

The Cascade volcanoes are a direct product of the subduction of the oceanic crust of the Juan de Fuca Plate. As the plate descends beneath North America the minerals within the plate release water due to increasing pressures and temperature in the mantle. This water has the effect of promoting melting of mantle rocks in North American kneel above the sub ducting plate. The melt rises, and eventually creates magma bodies in the lower crust, which in turn occasionally erupt in volcanoes at the surface. Once a pathway for the magma to rise to the surface is established a stratovolcano grows. A science paper that was published this year (2014) provided an image of the mantle and crustal rocks beneath Mt. Rainier.

Electrical resistivity in the Earth for a cross section beneath Mt. Rainier (the location is shown with a triangle).

The electrical resistivity of rocks is highly dependent on a couple of things; temperature, water content, and mineral content. In the figure you can see the cold oceanic crust of the Juan de Fuca plate descending (the blue streak on the left side of the figure). At about 50 km depth pressures are reached that cause a “de-watering” of the plate, which in turn, promotes the mantle melting. This is the red and yellow colors beneath Mt. Rainier. The dark red blob to the left of Rainier is likely it’s magma chamber, located between 5 and 10 km below the surface.

Although the volcanoes of Cascadia are not at all unexpected, seismologists did not understand why earthquakes seemed so infrequent in Washington. Most subduction zones would have a much higher rate of seismicity that was observed here — and this was the topic of discussion at Caltech in the late 1970s. Kanamori and graduate student Larry Ruff looked at subduction zones worldwide and plotted the size of the maximum observed earthquake as a function of the age of subducting plate and the rate at which the subduction was taking place. The analysis showed that rapid subduction of young oceanic plates resulted in very large earthquakes — mega thrusts.

Size of maximum observed earthquake as a function of rate of subduction and age of plate being subducted (from Ruff and Kanamori, 1980).

Tom Heaton and Kanamori used this “comparative subductology” and other geophysical constraints to postulate that the Cascadia subduction zone was capable of generating a mega-thrust earthquake — as large as magnitude 9.0 (paper appeared in 1984). The paper was meet with a great deal of skepticism because the seismicity along the Oregon-Washington coast was quite moderate. However, in 1987 Brian Atwater, a USGS geologist, found evidence of a major tsunami inland from the coast. Finally, Japanese seismologists had long been perplexed by a tsunami that hit the coast of Japan in 1700 but did not appear to be connected to any Japanese earthquake. Connecting the dots, seismologists were able to show that the 1700 Japanese tsunami was most likely created by an earthquake with a magnitude between 8 3/4 and 9 1/4 in Cascadia.

A trench through a coastal deposit in Oregon shows the sands brought ashore by the 1700 tsunami (Atwater et al., 1999).

Today there remains debate about the repeat frequency and size expected for the Cascadia earthquake, but it is now excepted that it is only a matter of time before it strikes. Mt Rainier seems like an ancient and noble giant benignly guarding Puget Sound. In fact, it is a very ephemeral geologic feature that will disappear in a few hundred thousand years, and most certainly will do violence to the equally temporary residents of the Pacific Northwest. Surely this makes climbing Rainier most interesting for a geoscientist!

Mt. Rainier from Paradise Ranger Station. This is the start of the IMG hike up the mountain – elevation of Paradise is at an elevation of 5200 ft, snow line is 7000 ft, and the top is 14,411 feet.

The expedition

The National Park Service keeps track of the number of people that attempt to climb Mt. Rainier and those that actually make the summit. The numbers are a little surprising; a little more than 10,000 attempt the ascent annually, and about half actually make it tothe top. This statistic is pretty robust for the last 25 years, and clearly establishes Mt. Rainier as a signifiant challenge. It is difficult to obtain quality data on the reasons that the success rate is so low, but the two most common anecdotes are weather and altitude maladies. The weather is easy to understand – the strong oceanic flow from the Pacific brings significant moisture inland to the mountain. When the flow encounters the mountain it is forced to flow over the elevation – which cools the air, which in turn forcing out the moisture, building clouds, and raining/snowing. The jump off for my expedition is the Paradise Ranger Station (elevation 5,200 feet), which has an annual rainfall of 126 inches. That is twice as much precipitation that is received at Ashford (elevation 1,760 feet) the home to International Mountain Guides, my chosen expedition team. Ashford is only a few miles west of Paradise, but the difference in rainfall illustrates the rapid change in weather and how the steep topography of Rainier controls its environment.

The challenge of the weather, and the fact that a significant stretch of the ascent is on ice are the reason that I chose to join an expedition rather that trying to cajole a few friends (whom are all as old as I am) to take a week off work and avoid ice crevices. I was not particularly worried about the physical part of the climb – running ultra trail races is more demanding – but I last climbed alpine glaciers more than 25 years ago, and as Shakespeare said “The better part of Valour, is Discretion”. There are three well regarded companies that provide a suite of guided expeditions up Mt. Rainier. I choose International Mountain Guides (IMG) for my adventure based on the rave review of a friend. I was a little nervous about joining a group expedition – in general, I am not a group kind of guy – but my friend assumed me that this was a great experience, and in fact, he was correct!

On Wednesday afternoon (Sept. 10) the 8 climbers in my expedition checked in with IMG in the small town of Ashford which is situated on the Nisqually River. The Nisqually is the main drainage of the southern half of Mt. Rainier, and I spent a couple of hours before checking in at IMG facility hiking along the river, and there are some spectacular exposures of the Paradise Lahar cut by the river channel. The age of the Paradise Lahar is probably about 7,500 years before the present, and the thickness exposed near Ashford is at least 100 feet — it must have been a significant and destructive event. The purpose of checkin is to assure that all the hikers are ready (so there is a very long equipment check), make introductions, and set expectations. The climbers in my group come from all walks of life; the director of strategy for a unit from a major company, a nurse, commodity trader, dentist, venture capitalist, lawyer and a financial analysts for an aerospace company. All have experience in mountains, although highly varied. Most importantly, all seem like fine people to send the next three days with tied to ropes, sleeping in crowed tents, and cursing crampons.

IMG delivers the expedition to Paradise. The wind is very strong, and the posted wind chill is 38 degrees.

The expedition started on Thursday morning — loaded up out packs at IMG headquarters and traveled east up the Nisqually River to the Paradise Visitor Center. I had weighed my pack early in the morning – full water bottles and mountaineering boots attached, and it was a marginally agreeable 46 pounds. But, alas, I forgot I had to take a group food package that would eventually become my dinner and breakfast the next two days. I don’t know how much my package weighed, but probably on the order of 5 pounds. So, loaded pack was about 50 pounds, about 45 pounds more than I ever run with on the trail. This was the only thing that I was truly dreading; pre hip and knee replacement 50 pounds would be no problem, but not positive what the next 3 days would hold.

Although the morning felt cool at Ashford, it was down right cold at Paradise. The wind was blowing strongly, and the posted wind chill was 38 F. IMG assigns 1 guide for every 2 climbers, so our team was 12 strong. Our lead guide was Cedric Gamble, and had the job of both assessing risk and assuring the team that were are super strong climbers; thus, we heard both the comment that the wind was amazing and not at all usual, and surely this weather will pass and all is good. I had my Garmin GPS watch and tracked the multi day climb. By my watch, the starting elevation was about 5100 feet. The path wanders out of Paradise and climbs up to Pebble Creek (this was about 3 miles by the route we were on, and a gain in elevation of 1900 feet). Hiking is easy even with the full pack, although the wind gust literally blew me over a couple of times.

Climbing the Muir Snow Field – putting on our mountaineering boots. The views to the south are spectacular with Mount Adams, St. Helens and Hood dominating the horizon.

Crossing Pebble Creek, the trail runs into the Muir Snowfield. The snowfield is not a glacier but a perennial mass of snow that is both slick and wet. The path for our expedition is to follow the snowfield up to Camp Muir, some 2.2 miles and 3000 feet elevation gain away. We changed out of our trail shoes into mountaineering boots for the trek up to Muir — this meant that my pack was lighter, but it also meant that I had to wear the plastic mountaineering boots, which are composed of an outer hard plastic waterproof shell and an insulating inner boot. These are heavy and warm, and I absolutely hate them. Too heavy and hot, it was like running in dress shoes. Over the next couple of days I would realize that these boots, when outfitted with crampons, where by far the most difficult aspect of the entire expedition.

IMG tent at camp Muir – a great restaurant.

About half way up the Muir snowfield we ran into another IMG team descending the mountain. A rather sobering and somber conversation took place between the two teams — the descending team had not been able to summit because of the high winds and had turned around at 13,000 ft elevation. It was very difficult to imagine that one could not summit on a clear day and that there were many factors that determine a successful climb. The rest of the first day’s climb is easy into Camp Muir. Muir is an assortment of small buildings situated on a ridge that separates the snowfield from the Cowlitz Glacier. The buildings serve as a way station for climbers, and IMG has a small room there where the team can bunk down for the night. The room is about 20 x 20 feet, and is a couple of plywood shelves to role out your sleeping bags. Pretty small quarters, but shelter from the wind (it also turns out the expedition members don’t really snore nor have nocturnal gaseous emissions). The IMG guides have a tent that serves both as the communal restaurant and their sleeping quarters. Dinner at the IMG tent was a very pleasant surprise, and suddenly I felt very guilt for my mental grousing about carrying that five pounds of community food. Dinner serves as a chance for all the team members to learn about each other — and I learned far more than I ever thought possible about pediatric dentistry, the incredible attributes associated with living in Coeur d’Arlene and climbing Aconcagua (I am jealous).

A sketch of the east side of Rainier (from Crandell, 1969). The path for our ascent crosses the head of Cowlitz Glacier, then follows the rock spur below Gibraltar Rock up to cirque of Ingraham Glacier over looking Little Tahoma Peak. The original summit of Rainier went from Point Success to Liberty Cap – before a major eruption 5500 years ago, Rainier was 16,000 feet high.

Friday morning the trek really begins — we practice ice axe skills, crampons on ice, and roping up groups of climbers. We cross over Cowlitz Glacier and then have a short hike up what is called Cathedral Gap; the Gap section is bare rock and our passage is in our crampons, a first distasteful snippet of walking on rock and dirt while wearing sharp spikes of metal. After a relatively short hike we arrive at the high camp located on the upper reaches of Ingraham Glacier. Ingraham Flats is a moderately sloping section of ice at an elevation of 11,500 ft. The camp is four tents for the climbers, two more tents for the guides, and small kitchen carved in the ice and snow. The views are breath taking; the sounds are unnerving. The Flats are framed by Gibraltar Rock to the south and the Disappoint Cleaver to the north. Gibraltar lords over the camp as vertical cliff of nearly 800 feet, composed of layers of eruptions and lahars past. Every few hours rocks fall from the cliffs, a not so subtle reminder that Rainier is always changing. I also peer up at the ice of the head of Ingraham Glacier and think about the disastrous ice fall in 1981 that took the lives of 11 climbers. It is the worst climbing accident in American history, and to be in it’s shadow is a reminder that gravity is unforgiving. I decide it is best not to ask about the accident with the other members of the team.

High Camp – Ingraham Flats, on Ingraham Glacier. Over my left shoulder is the Cleaver, a nasty stretch of rock that is the heart of the climb to the summit (which is visible some 3000 feet above us in the center of the photo).

We have “dinner” at 3:45 on Friday so that we can be in the tents by 5:30 pm. This is to facilitate a 1:00 am wake up call and a 2 am debarkation for the summit. Sleep that night seems fine for me (better than most of my hotel visits to Washington DC every couple of weeks), but most of the team is beginning to feel the effects of altitude. Living at 7400 feet elevation has its rewards! Breakfast at 1:15 is instant oatmeal and coffee. I opt for multiple cups of coffee and pass on the oatmeal. At 11,500 the boiling point of water is about 185 degrees F instead of the sea level value of 212 degrees, so the coffee is tepid. No matter, it is still nice fuel. The morning is cool – my thermometer that I left just outside the tent reads 28 degrees F. The wind is still though, so it is quite easy to dress comfortably. Unfortunately, before we rope up to cross the glacier and head up the cleaver we remove layers to assure that we don’t over heat on the climb. That means it is cold when we start our trek. The climb is steep, and the half moon gives a nice glow, but mostly you look at the ground in front of you illuminated by your head lamp as travel.

High Camp from Disappointment Cleaver. This picture was taken on the descent, mid-morning. The tiny dots are our tents at the high camp.

The Cleaver is an 800′ elevation climb on rocks. It is technically the most difficult part of the entire ascent. Not particularly physically challenging, but the combination of large blocks of Andesite, crumbly scoria, and even some obsidian means that every step of the crampon encased boot is a challenge. Around 3:30 we finally finish with the Cleaver, and are back on the welcome crunch of ice. The guides lead us back and forth up the south face of Rainier until we finally cross the lip of West Crater about 7 am. The sun is just rising, and the winds are calm. Unbelievably majestic. Crossing the lip of the crater is considered a summit, but I know that we are across the crater from the true high point on Rainier. Several of us drop our packs and hike the couple of hundred yards to the northwestern rim and climb up to the Columbia Crest, the “true” summit of Rainier. We arrive there about 7:30, and revel in the success of the trek.

Summit Team at Columbia Ridge. Just below me is the USGS marker for the elevation. The marker was placed in 1956 – my birth year.

The views from the summit are both spectacular and disappointing. The skies are clear, and one can easily pick out every major volcano in the Cascades well into Oregon. However, the humidity in the air gives a sense of haze in the distance that one never sees from the summit of a 14er in Colorado. The crater itself is magnificent. A stone circle created by an eruption a few thousand years ago, it has dozens of fumaroles all along the rim. Wisps of steam give hint to the hot rock not far below the surface. I applied the sniff test to several of the fumaroles, and only caught the faintest notion of sulfur; mostly was just moist stream.

West Crater

Around 8 am we began our long trip reversing our footsteps back to Paradise. By my Garmin we had hiked 12.2 miles and with the ups and downs (mostly ups!) we had gained 9600 feet elevation. The journey down was more difficult than I expected – not because it was a physical challenge, but because the sun was shining and the views were extraordinary! I wanted to stare and ponder the magic landscape, which meant I did not want to focus on traveling on a rope along an icy and steep trail. The descent back to the top of the Cleaver went by uneventfully, and I was able to get a picture of the moon setting over the top Mt. Rainier.

Rainier Descent – moon setting over the rim of the crater.

The traverse down the Cleaver was by far the most difficult part of trip down. We are all a little tired, and those damn boots and crampons! I did manage to stab myself in the left leg with the crampons from my right boot. I drew blood, and it is only appropriate as a sacrifice to a great mountain. We finally get back to high camp for a brief rest, and some lunch. The journey back to Camp Muir was pretty trivial, and we stop for some water at the IMG tent. All that stands before us and the end of the trek is the Muir snowfield – how hard can that be? However, we decide to keep on the crampons to cross the field since it is soft and slick. Drudgery! But unexpectedly, the slog was made tolerable by the fact that it was Saturday, and there was a menagerie of folks climbing the snowfield from Paradise. We saw people in shorts, skirts, tennis shoes, formal wear, and of course, flip flops! Consider that these snowfield adventurers had invested hiking more than 3 miles and 2000 feet elevation gain, you have to wonder how much thought went into their apparel. One of the most humorous moments of the entire journey was when one of our teammates engaged a woman in a long dress in conversation on the snow and said “you can do it!”. He was being positive, but also preposterous! Finally, at Pebble Creek we shed our boots and crampons, and all is right with the universe.

The trek up Rainier was a spectacular experience. I am fortunate to have combined the wonder of a high mountain climb with a favorable group of colleagues, and wonderful guides. I could not have been more delighted – but of course, I got something a little extra. On the flight home Sunday morning the American Airlines flight to Dallas took off to the south out of SEATAC and flew towards Rainier. Once we reached the Nisqually River the pilot took a hard left and flew right over Paradise, and suddenly out my window was the entire picture of my trek. Fabulous!

Passing over Rainier on the way home (9/14/14). The image is high resolution so click on it and expand. The various way stations are labeled.

Rainier will one day erupt, and will no longer be the high point of the Cascades. I am grateful that I got to experience the great mountain in its finest state – and mood.